We Need to Talk About Scaffolding

A new replication challenges the evidence behind one of education’s core ideas.

After my last post on Vygotsky, I was contacted by the lead author of a remarkable new study, a rigorous replication of a famous experiment which found that the classic scaffolding rule of giving more help after failure and less after success provided no measurable benefit for children’s problem solving,

In the late 1970s, three psychologists published a small experiment that would go on to fundamentally reshape classroom teaching and tutoring over the next 50 years. Working with just thirty-two children, they claimed to have discovered the mechanics of “scaffolding”; that when an adult tutor adjusts their level of help based on the child’s success or failure, learning dramatically improves.

It was a beautiful idea, and it took hold. Textbooks, teacher-training courses, and observation frameworks all began to echo its logic: more help after failure, less help after success. Teaching became framed as a kind of calibrated dance of contingent support, the elegant give-and-take between expert and novice.

In their foundational 1976 paper, Wood Bruner and Ross defined scaffolding as a process enabling “a child or novice to solve a problem, carry out a task or achieve a goal which would be beyond his unassisted efforts.” The metaphor was compelling: like builders’ scaffolding, instructional support should be temporary, adjusted to need, and gradually removed as the learner gains competence.

In 1978, as Vygotsky’s writings were introduced to Western audiences through Mind in Society, the scaffolding study was reinterpreted within this new Vygotskian framework. Although the study was not included in that book, its ideas were quickly reinterpreted through this new lens. Educators and psychologists began to treat scaffolding as the practical realisation of Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

From that moment, scaffolding and the ZPD became conceptually fused in Western educational thought. The metaphor appeared to give Vygotsky’s abstract theory a visible, classroom-ready form, while offering teachers a compelling model of support and gradual release. The combination was irresistible: a vivid image, a powerful theory, and what seemed like solid experimental evidence. Few questioned its foundations, until now.

The Original Study

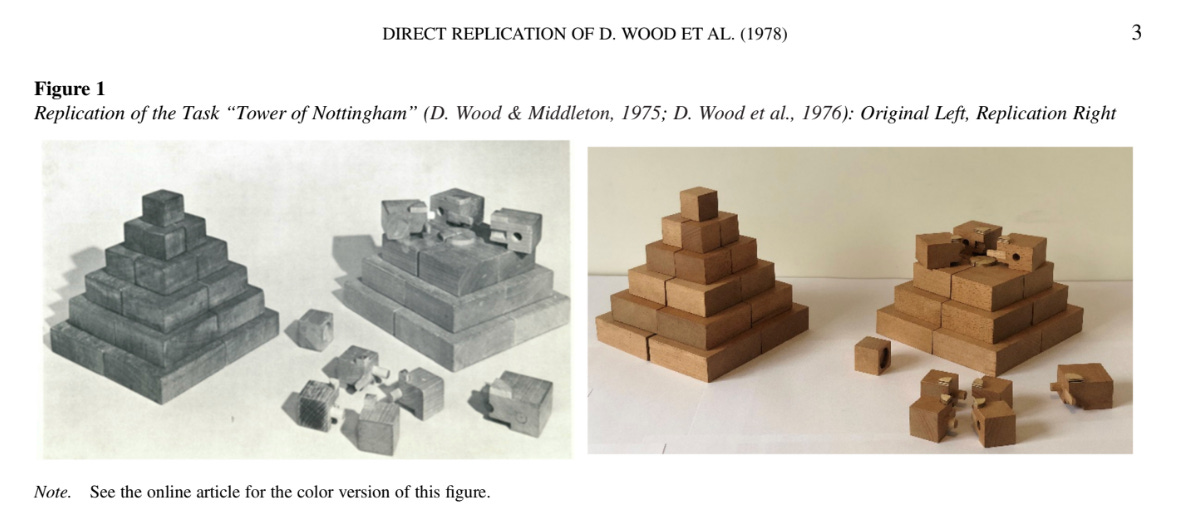

As noted earlier, the concept of scaffolding was famously defined in a 1976 descriptive paper by Wood, Bruner, and Ross; The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving. (In fact Paul Kirschner and I dedicated a chapter to that paper in our book How Learning Happens.) That paper was based on observations of a single tutor teaching children a complex construction task . Building on this and a 1975 study of mothers as teachers, David Wood, Heather Wood, and David Middleton published a follow-up

This 1978 experiment is the study that became canonical. It tested the “contingent shift principle” by comparing contingent instruction against three other, less-responsive teaching methods. The results, based on a tiny sample of 32 children (N=8 per condition), claimed to find a “large effect” for the contingent strategy, reporting implausibly huge effect sizes. Despite its colossal status, Smit et al. note that “surprisingly, no direct replication of D. Wood et al. (1978) has been reported (p.3)” in the 45 years since.

The study identified six core scaffolding functions that remain foundational today: recruitment (gaining interest), reduction in degrees of freedom (simplifying the task), direction maintenance (keeping on task), marking critical features (highlighting important elements), frustration control (managing stress), and demonstration (modelling techniques). Critically, three of these functions were motivational and three cognitive, a balance often lost in contemporary applications that overemphasise cognitive support.

The concept of “contingent control” emerged as the study’s most influential contribution. This idea was based around the observation that successful tutors continuously adjusted their support based on moment-to-moment performance, following what researchers called the “contingent shift principle”: increase control when the learner fails, decrease control when they succeed. This created a “region of sensitivity” to instruction where children never succeeded too easily or failed too often.

The study’s influence proved extraordinary. With approximately 9,000-10,000 citations, it became one of the most cited papers in educational psychology. Though Wood et al. didn’t originally cite Vygotsky’s work, the scaffolding concept was quickly connected to the Zone of Proximal Development by later researchers, providing an elegant framework for implementing Vygotskian theory in practice, which was vague in terms of implementation. The construction industry metaphor; temporary support structures removed once no longer needed, proved intuitive and powerful, bridging constructivist and instructivist educational philosophies.

But amazingly, the original study had critical limitations that went largely unexamined for decades. The sample was extremely small: N=8 per condition, 32 total participants. This produced very large confidence intervals and imprecise effect estimates. The reported effect was classified as “huge” by statistical standards, but such large effects from small samples are precisely the kind that often fail to replicate. But remarkably, (and I had to check this with the lead author of the study) no close replication had been conducted in the subsequent 45 years, despite the study’s colossal status in educational policy and practice.

Replication of the Original Scaffolding Study

In 2021–2022, a team led by Nienke Smit at Utrecht University undertook something incredibly rare in education: a direct, preregistered replication of Wood et al.’s 1978 experiment. Their brilliant study painstakingly reconstructed the original protocol, the wooden construction task, the instructions, even the coding procedures. They recruited 285 children (compared to the original sample of 32), used multiple trained tutors, and conducted the study across 26 locations. They preregistered their hypotheses and analysis scripts. They even used independent coders blinded to conditions. The results?

Children who received contingent instruction performed no better than children taught through demonstration, verbal instruction, or the “swing” condition (alternating between minimal and maximal help). The outcome scores, efficiency scores, and autonomy scores showed no significant differences between conditions. The Bayes factors provided strong evidence for the null hypothesis: contingent instruction, as operationalised by Wood, simply didn’t work.

This isn’t a minor methodological quibble. The replication successfully reproduced nearly everything else from the original study: the coding granularity, the children’s performance in the three control conditions, the duration of instruction, even the tutor adherence rate (68.9% in the replication versus 70% in the original). What they couldn’t reproduce was the only thing that mattered: the scaffolding effect.

What Went Wrong?

This pattern is depressingly familiar in education research. The field has long tolerated methodological standards that would be considered laughable in medicine, engineering or even psychology (which has its own replication problems.)

Education research tolerates remarkably low methodological standards. Observational studies are treated as definitive evidence, theoretical papers spawn movements, and sample sizes barely adequate for pilots, become foundations for policy.

Compare this to the standards that govern drug approval. The FDA requires Phase III trials with hundreds or thousands of participants, randomised control groups, pre-registration of hypotheses, and independent replication before a drug can be prescribed. Even then, post-market surveillance continues to monitor for unexpected effects. The process is slow, expensive, and frustrating for researchers eager to help patients. It is also the reason we no longer prescribe thalidomide to pregnant women.

Statistical power, pre-registration, and replication (cornerstones of credibility in other sciences) remain rare in education. The result is a literature heavy on metaphor and aspiration but light on causal evidence. The scaffolding study was not an anomaly; it was a symptom of a broader pattern in which intuitively appealing theories outpace the data that support them.

Education research suffers from a certain kind of evidential laxity: a tendency to accept claims on the basis of face validity, theoretical elegance, or ideological appeal rather than rigorous empirical testing. The scaffolding story exemplifies this perfectly. A study with 32 children, producing implausibly large effects, became gospel. No one demanded replication. No one questioned whether effect sizes of d = 3.25 to 5.69 were remotely plausible.

With only eight children per condition, the original study was vulnerable to sampling error, chance findings, and the ‘winner’s curse’ (where initial effect size estimates from small studies tend to be grossly inflated). When Smit’s team powered their study properly and removed these sources of bias, the effect vanished.

This should matter. A lot. But here’s what makes this story particularly troubling: despite weak empirical foundations, scaffolding has become doctrinal in education. It’s been presented not as a promising hypothesis requiring further testing, but as established fact. Teachers are evaluated on whether they scaffold or not. Policy documents mandate it. Critics are dismissed as opponents of “student‑centred” learning.

But as the problem isn’t scaffolding as a concept; it’s scaffolding as it was operationalised and subsequently enshrined. Wood et al’s contingency rule sounds deceptively simple: more help when the child fails, less when they succeed. But what constitutes “failure”? How much help is “more”? When exactly should a teacher intervene? How long should they wait?

The project rationale itself raised red flags. The researchers noted that adaptive instruction “is currently widely promoted and implemented”... Yet, as they point out, a direct replication was needed to “resolve some methodological issues” and “find substantiation” for a principle that had been widely adopted without such rigorous testing. Only two conceptual replications had been conducted, and they also suffered from “imprecise estimates due to small samples”.

A Conversation with the Lead Author

When I asked lead author Dr. Nienke Smit how educators should interpret these findings, she cautioned against abandoning the concept of scaffolding altogether:

“Timing and updating real-time predictions about what is needed is key for educators,” she told me. “Also sitting with the discomfort of seeing a child struggle is needed — but don’t walk away. Keep paying attention as a teacher and work towards ‘leading by following’ instead of taking over.”1

This I think, is a far more sophisticated take than the contingency rule ever allowed. “Leading by following” captures something essential about responsive teaching that the algorithm missed entirely. The phrase “sitting with the discomfort” is particularly telling. The contingency rule promised to eliminate that discomfort through algorithmic clarity, but teaching requires tolerance for uncertainty about whether this particular child needs more time, a different approach, or simply your presence whilst they work through difficulty.

Smit suggests that the absence of effects may in fact be partly developmental. “We piloted the task with four-year-olds before data collection, and the older three-year-olds performed much better than the younger ones,” she said. “Language ability varied widely, and loss of attention was common. My hypothesis would be that there was something going on with sustained or joint attention.”

This points to a deeper problem: three-year-olds are still developing the attentional resources needed to form a stable functional system with an adult tutor. The contingency rule assumes a child who can maintain task focus, register success and failure consistently, and benefit from calibrated adjustments. But development is messier. Some children that age simply cannot yet sustain the kind of stable, goal-directed partnership that contingent teaching requires.

Smit shared that she had written to David Wood after publishing the results. “He told me that the ecology of infants has changed a lot these days,” she recalled. “However he still thought the task should be learnable for preschoolers. And I agree — it’s a beautiful task, and still hard enough for them.”

Wood’s comment about changing ecology is intriguing but raises questions. What has changed? Without specificity, this risks becoming post-hoc reasoning that protects cherished beliefs from disconfirmation.

Dr Smit’s closing reflection to me is really important I think: “I think a lot can be gained from rethinking what failure is and what help is. Some struggles and mistakes are not failure; some moments of well-intended help are not help but control. I would like to invite teachers to see ‘help’ as a practice — something you can always learn more about.”

The contingency rule reduced teaching to a binary: success or failure, more help or less. But struggle isn’t always failure; it’s often the mechanism of learning. A child working through difficulty, making errors, trying again is learning, even without immediate success. Conversely, help that removes all difficulty may feel supportive but undermines the development of independence. Smit’s distinction between help and control is crucial: when a tutor takes over completely, it may look like scaffolding but functions as its opposite.

So What Actually Happened in the Original 1978 Study?

The replication offers tantalising clues. When Smit’s team compared their results to the original across all four conditions, three looked remarkably similar. The demonstration, verbal, and swing conditions produced nearly identical outcomes in 1978 and 2022.

Only one condition stood out as wildly different: the contingent instruction group in the original study. Those eight children were dramatically more active, attempting the task far more frequently than children in the 2022 replication.

This hints at something the original researchers couldn’t have known: the effect they observed might have had nothing to do with the teaching method itself. Perhaps those particular eight children were simply more motivated, more confident, or more willing to engage. With only eight children, random assignment offers no protection against such imbalances.

The Hierarchy and Timing Problem

The original operationalisation assumed a hierarchy of support, from low control (general verbal encouragement) to high control (physical demonstration). But is physical involvement always “more” support than verbal guidance? Consider a tutor who verbally micromanages every step versus one who gently gestures toward relevant materials. Which provides more control?

The assumption that you can rank support types on a single dimension ignores context, individual differences, and the bidirectional nature of teaching. Children don’t just receive support passively; they actively seek it, refuse it, misinterpret it. Some children asked for more help immediately after receiving help. The tutor aimed to maximise independence; the child wanted to complete the task quickly. Whose goal should prevail?

Teaching is synchronisation, not unidirectional control. Help‑seeking behaviours and help‑providing behaviours mutually influence each other. A fixed protocol that doesn’t allow tutors to adjust, repair, or self‑correct based on children’s responses is bound to struggle. Yet this is precisely what the contingency rule demanded: lock yourself into providing more or less help based on the previous outcome, regardless of what the child is actually doing or wanting.

Perhaps the most fundamental issue is timing. When should a tutor intervene? The original protocol required immediate response to success or failure. But children vary enormously in how they process information, how long they need to struggle productively, and how they signal their need for help.

Some children in the replication were quiet, shy, hesitant. Others were highly energetic, easily distracted, making many attempts. Should “not starting” count as failure? Should the tutor wait until frustration sets in? What counts as “productive struggle” versus unproductive floundering?

The Implications

This replication has profound implications, not just for scaffolding but for how education engages with evidence. First, it demonstrates the danger of building policy on small, underpowered studies. Wood’s original experiment, with eight children per condition, should never have become the basis for universal teaching standards. The effect sizes were implausibly large. The confidence intervals were enormous. Yet the field embraced it uncritically, perhaps because it confirmed what people wanted to believe.

Second, it reveals how education insulates itself from disconfirmation. In medicine, a failed replication of this magnitude would trigger immediate reconsideration. In education, the misapplication of ideas usually continues unabated, largely because the concept has become ideological rather than empirical. To question it is to be against long established orthodoxies even when the evidence base has crumbled.

Where Do We Go From Here?

If the contingency rule (“more help after failure, less after success”) doesn’t hold up empirically, it doesn’t mean scaffolding is useless; it means the rule itself is too mechanical for something as complex and dynamic as human learning.

Does this mean scaffolding is worthless? No. The intuition behind it remains important: learners benefit from support that’s calibrated to their current capabilities and gradually withdrawn as competence develops. But we need a more sophisticated understanding of what this means in practice.

These points are really well discussed in The Scaffolding Effect, a recent book by Rachel Ball and Alex Fairlamb who make the claim that scaffolding is not just a teacher’s response to a child’s failure, but the entire set of relationships, structures, and environments that enable learning and resilience. And crucially, they argue that effective scaffolding is not so much about helping in the moment but about designing systems that anticipate and enable growth.

You can’t scaffold your way out of a bad curriculum and poor instruction. Schools and teachers create scaffolds when they design routines, norms, and environments that allow students to take risks safely.

What does this mean for tutoring?

This research suggests that effective tutoring is far more complex than following the simple 1978 rule of “more help on failure, less on success”. The fact that this rigid, formulaic approach failed to improve children’s learning in this large replication study highlights a crucial and difficult element of teaching: timing.

Tutors must constantly make “uncertain judgments” about when to intervene and what constitutes “failure”. The original researcher, David Wood, reflected on this exact problem 25 years after his original experiment, in a passage cited by the new study:

We have discussed how to provide tutorial support, and now we return to the issue of if and when to intervene in the first place. I used to think this was a relatively straightforward issue, but not anymore, […] Can you say ahead of time how long you should leave a particular learner to struggle before you provide any help, for example? No? Me neither. This has far reaching consequences for our understanding of what it takes to become an effective tutor. (p. 16)

This is refreshingly honest and I think captures precisely why the 1978 protocol failed to replicate. A fixed rule cannot account for the “far reaching consequences” of timing. For tutors, this means there is no universal algorithm for scaffolding. The key skill is not applying a formula but making sophisticated, real-time predictions about a learner’s needs. It involves navigating the uncertain boundary between difficulty that aids learning and difficulty that impedes it, a human judgment that, as this replication shows, cannot be successfully replaced by a static script.

Primary sources:

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89–100.

Wood, D., Wood, H., & Middleton, D. (1978). An experimental evaluation of four face-to-face teaching strategies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 1(2), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502547800100203

Smit, N., de Kleijn, R., Wicherts, J. M., & van de Pol, J. (2025). What it takes to tutor—A preregistered direct replication of the scaffolding experimental study by D. Wood et al. (1978). Journal of Educational Psychology, 117(8), 1313–1329. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000965

(N. Smit, personal communication, [22.10.2025])

“You can’t scaffold your way out of a bad curriculum and poor instruction. Schools and teachers create scaffolds when they design routines, norms, and environments that allow students to take risks safely.” This part! Thank you!

I've written my thoughts on this finding, based on your article, here https://dahuzi888.substack.com/p/iteration-over-replication-in-education