In Search of Vygotsky

How the Zone of Proximal Development Became Education's Most Misunderstood Idea

“Vygotsky’s works have been used as the basis for certain socioconstructivist school reforms that he would surely have completely disapproved of.”1

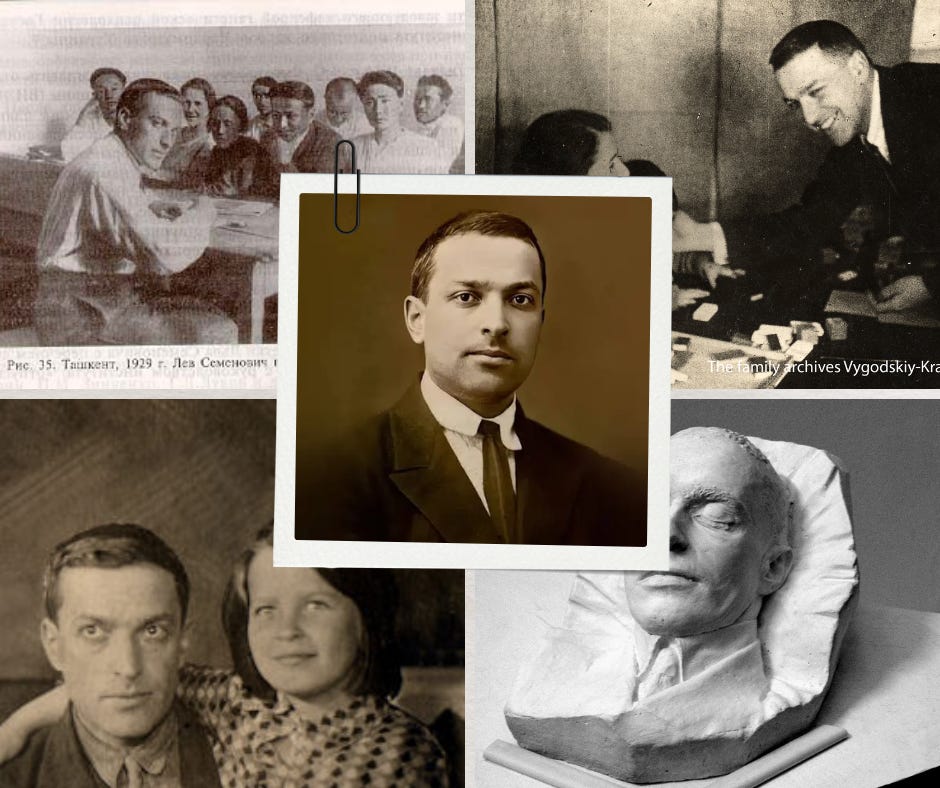

Few figures in education have enjoyed a stranger afterlife than Lev Vygotsky. Dead at thirty-seven from tuberculosis in 1934, his works banned for two decades under Stalin, he was resurrected half a century later not in Moscow but in California.

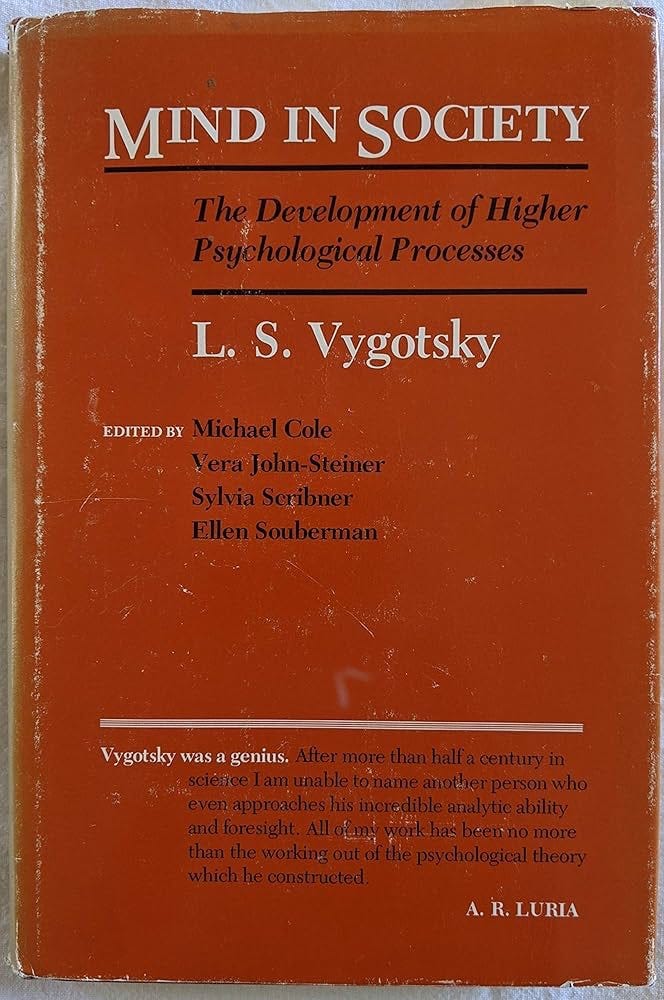

In 1978, a slim English volume titled Mind in Society introduced Vygotsky to the West. Edited by Michael Cole and colleagues, it stitched together fragments from his unpublished and translated writings for an American audience. The result was a revelation: here was a psychologist who seemed to place social interaction, collaboration, and language at the heart of learning. The Zone of Proximal Development became a new mantra. Teachers were told that “learning is social,” that knowledge is “co-constructed,” and that classrooms should become communities of inquiry.

However, when the Collected Works finally appeared in English between 1987 and 1999, many scholars found a more complex and dialectical philosopher of instruction, not the high priest of discovery learning he had been made out to be. Yet by then, the interpretation was already entrenched in education departments, textbooks and policy documents.

As Michael Cole put it at the time, “Vygotsky has become a fad, and, as with all fads, the greater notoriety brought with it both genuine evolution and dimestore knockoffs.2 The problem with Mind in Society is that it was never meant to stand alone. It was a digest, not a doctrine. And what passed into teacher training colleges, curriculum frameworks, and education departments was in many senses a reconstruction rather than a translation.

The Two Vygotskys

There are, broadly speaking, two Vygotskys. The first is the Anglo-American Vygotsky; social, collaborative, constructivist. He appears in Mind in Society and its successors, cited alongside Bruner, Rogoff, and Wertsch. His classroom is full of dialogue, peer tutoring, and scaffolds. He is invoked to justify discovery learning, group work, and “authentic” tasks.

On the other hand, there is the Russian Vygotsky; dialectical and instructional, insistent on the systematic transmission of conceptual tools. This version appears in the Collected Works, the notebooks, and the research of his successors: Menchinskaia, Galperin, Davydov. His classroom centres the teacher as the one who introduces learners to forms of thought they could never reach alone. Knowledge is not discovered but revealed through explicit, structured instruction. The teacher does not step back; the teacher steps in.

These are not minor differences of emphasis. They represent fundamentally different philosophies of teaching and learning. Yet both claim the authority of Vygotsky’s name, and both cite the same handful of concepts: the Zone of Proximal Development, scaffolding, internalisation. How did one thinker come to stand for such contradictory ideas?

The answer lies in the peculiar history of how Vygotsky arrived in the West. Mind in Society appeared in 1978 at exactly the moment Western education needed an alternative to behaviourism. The social Vygotsky fitted the progressive mood perfectly: he offered a theoretical foundation for collaborative learning, discovery methods and child-centred pedagogy. He was institutionalised in teacher training programmes before the full body of his work had even been translated.

Misreading the Zone

The Zone of Proximal Development is perhaps the most dominant concept in modern education, invoked with the certainty of an article of faith. It is worth returning to what Vygotsky actually wrote, (albeit in translation). He defined the Zone of Proximal Development as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” The critical word here is distance. The zone was conceived as a diagnostic measure, a way of gauging the gap between what a learner can do alone and what they might achieve with instruction.

It was not, in itself, a prescription for how to teach. Yet somewhere between the Russian original and the Anglo-American classroom, this distinction collapsed. The zone ceased to be an analytical tool for understanding development and became instead a pedagogical method: scaffolding, peer collaboration, guided discovery. What had been a way of measuring potential became conflated with the means of realising it.

Paul Kirschner’s distinction between epistemology and pedagogy helps to clarify what went wrong in the Western reading of the Zone of Proximal Development. Where he warns that discovery learning confuses doing science with learning science, the same mistake recurs in education when teachers confuse analysing development with teaching within the zone.

The phrase Zone of Proximal Development does not come from a unified, definitive work. It comes from Mind in Society, that assemblage of edited writings, and it has been reinterpreted through a particular pedagogical lens. In the original formulation, the zone described a dialectical relation between instruction and development. It was about how teaching creates new forms of consciousness, not merely by supporting what learners already half-know, but by introducing them to conceptual structures they could not have reached on their own.

One of the most persistent misunderstandings of the Zone of Proximal Development is that it has been drained of content; the “what” of teaching. As Seth Chaiklin points out, most modern readings treat the ZPD as a kind of social space where a more capable person helps a less capable one perform a task. But this popular image of guided support or “assisted performance” misses the point entirely. Vygotsky was not interested in any and every kind of help; he was concerned with what kind of instruction produces development.

The zone, Chaiklin explains, refers to the relation between teaching and the maturing psychological functions that move a learner toward the next stage of thought . In the school years, those functions are tied to the acquisition of scientific concepts; the abstract systems of meaning that enable conscious awareness and volition . When the ZPD is treated as a general process of support, detached from this developmental content, it becomes a hollow technique. The result is a vision of education preoccupied with assistance rather than transformation. Vygotsky’s original idea was far more demanding: that teaching should aim at the formation of new conceptual structures, not the mere completion of tasks.

The Scaffolding Illusion

The conflation of the Zone of Proximal Development with scaffolding has arguably been the most consequential misreading of Vygotsky in Western education. As Peter Smagorinsky explains, the scaffolding metaphor was not Vygotsky’s creation but that of Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976), who coined it to describe one-to-one tutoring sessions with preschoolers. Their model of a tutor providing graded support until the child could act independently was based on an early, unreliable translation of Thought and Language, and it bore little resemblance to Vygotsky’s broader developmental theory. In Smagorinsky’s words, “Vygotsky, however, never offered scaffolding as a pedagogy.” To treat scaffolding and the ZPD as interchangeable is thus to misrepresent both: scaffolding is a useful instructional tactic, but the ZPD is a theoretical account of how instruction reorganises consciousness over time.

For Vygotsky, the zone was not primarily about collaboration or scaffolding. It was about the transformative power of systematic instruction. The teacher’s role was not to facilitate discovery but to transmit the tools of scientific thinking, to lift learners from spontaneous, everyday concepts to systematic, disciplined thought. Collaboration and dialogue were means through which this transmission occurred, not ends in themselves.

This distinction is crucial. Scaffolding and peer dialogue are useful, but for Vygotsky they were vehicles through which teaching induces qualitative shifts in consciousness. Collaboration without conceptual clarity merely rehearses everyday ideas. The purpose of teaching is not to co-construct reality but to reveal structures of thought learners could not reach alone.

Yet in contemporary education discourse, the Zone of Proximal Development has become synonymous with a general principle of support and social interaction. It is invoked to justify group work, peer tutoring and discovery learning, approaches that Vygotsky might well have recognised as insufficient. The zone has been transformed from a dialectical metaphor about the growth of consciousness into a pedagogical slogan about working together.

The Davydov Problem

The confusion about Vygotsky’s legacy is not limited to Western misinterpretation. Even within the Soviet tradition, the picture is complicated. Consider Vasily Davydov, whose developmental learning system claims Vygotskian heritage. Davydov’s affiliation with Vygotsky passed through Elkonin, who had collaborated with Vygotsky on research about the role of play in preschoolers. The Elkonin-Davydov system exploited this work, taking play as a model: in play, children follow their own wishes and appear to enjoy complete freedom. The teaching system uses play as a pattern by setting up learning conditions so that the activity of learning acquires the same properties as play.

Yet in doing so, Davydov and his colleagues transposed to school-age children a process of learning that Vygotsky had reserved for preschoolers. This is not a minor adaptation; it erases the specificity of learning at school age. More troublingly, in a detailed analysis of Chapter 6 of Thinking and Speech, Davydov argues against the distinction between scientific concepts and ordinary concepts. He reproaches Vygotsky for nominalism and rejects the conception that transmission of scientific concepts permits children to access the next stage of development, dismissing this as incompatible with activity theory. Instead, Davydov turns toward Rubinstein and Piaget to propose an operational learning theory centred on pupils discovering generalisations through arranged activities.

The irony is sharp: Davydov later proclaimed himself Vygotsky’s successor in educational themes, trading on the growing international interest in Vygotsky’s work. Yet a detailed review of his intellectual itinerary reveals fundamental differences. The constructivist classroom that bears Vygotsky’s name looks far more like Davydov’s adaptation than like Vygotsky’s own vision. This confluence occurs through a decontextualised interpretation of the ZPD, disconnected from the problem of transmission of academic knowledge, making it instead a social space where the teacher’s actions guide the child’s discovery. This understanding is made possible entirely on the basis of Mind in Society but does not stand up to a chronological reading of the Collected Works.

Crucially, even Alexander Luria, who curated the texts that compose Mind in Society, may have anticipated or at least prepared this sociocultural interpretation. The texts were carefully selected; the sociocultural reading was not accidental. Yet the question remains: have we read Vygotsky incorrectly, or have we simply followed a path that some of his own successors prepared?

Lost in Translation

The deepest distortions of Vygotsky’s thought however, did not come from ideology but from translation. As Andrey Maidansky observes, key Russian terms such as smysl (смысл) and perezhivanie (переживание) simply do not exist in English in any adequate form, and when rendered through the lens of British empiricism and American pragmatism, they lost their philosophical weight. Smysl, often flattened into “meaning” or “sense,” in Vygotsky’s own usage refers to the living significance that a word or concept takes on within consciousness, a fusion of purpose, essence, and affect, not a mere semantic label. Perezhivanie, usually reduced to “emotional experience,” denotes the unity of thought and feeling, the way the world is refracted through the emotional life of the mind.

As Zavershneva and van der Veer have shown, these ideas form the backbone of his mature systemic psychology, yet much of that richness evaporates in translation. When smysl becomes “meaning” and perezhivanie becomes “feeling,” the dialectical pulse of Vygotsky’s psychology gives way to the observational language of social constructivism. The result, as Daniels and Cole both noted, is a thinker made fluent in English but mute in his own tongue; a Vygotsky translated but not understood.

Michael Cole’s The Perils of Translation offers the clearest account of how linguistic slippage distorted Vygotsky’s original meaning. The problem, he explains, centres on the Russian term obuchenie, (обучение) which denotes the reciprocal process of teaching and learning; two sides of a single pedagogical act. When Mind in Society appeared in English, obuchenie was rendered variously as “learning” or “instruction,” a shift that fractured this unity and led readers to treat Vygotsky’s developmental theory as a psychology of individual learning rather than a dialectical account of how instruction generates development.

The issue of central concern is that the unwary reader is likely to draw incorrect inferences about the relationship between “learning” and “development” that occur in a school context, assuming that these terms meant to Vygotsky more or less what they mean to English-speaking readers today. As I demonstrate next, this assumption is wrong and the implications of translating the term obuchenie as learning, instruction, or another set of related terms, differentially encourage rethinking other of Vygotsky’s texts for their theoretical implications.3

Cole concedes editorial responsibility, noting that English readers “are likely to draw incorrect inferences about the relationship between ‘learning’ and ‘development’,” since in Russian the word already implies “a double-sided process” involving both the child and the organised environment created by the teacher . The result, as Andrew Sutton observed decades earlier, is that translation “renders much Russian work in English wholly meaningless,” because obuchenie embodies a dialectical relation in which “not only do children develop but also we adults develop them”.

So, where English versions of Vygotsky often read as if he’s talking about how individuals learn, the Russian original is about how people teach and learn together; a single dialectical act that produces development. Losing that unity is one of the main reasons the Western Vygotsky was reinterpreted as a constructivist champion of individual discovery, rather than as a theorist of instruction.

What Vygotsky’s Student Actually Found

The debates within Soviet psychology mirror the debates we still have today. Natalia Menchinskaia, one of Vygotsky’s closest collaborators, devoted her career to studying how children assimilate school knowledge. Unlike Davydov, she worked directly with Vygotsky and completed her dissertation under his supervision on the development of schoolchildren’s arithmetic skills. She headed the Laboratory of the Psychology of Learning and Intellectual Development in the Psychology Institute for almost forty years, yet remains little known in the West, her works overshadowed by those of her contemporaries who aligned more closely with activity theory.

Menchinskaia endeavoured to follow, as closely as possible, the internal processes and stages of the assimilation of school knowledge in the mind of every child. This was precisely the research programme Vygotsky had outlined at the end of his life: “Pedagogical analysis will be always oriented towards the interior... It must clear up for the teacher how the processes awakened by school teaching take place in the mind of each child.”4 Her work can be regarded as Vygotsky’s programme restored from where he left it: to follow the effects of formal learning on child development.

Her experiments showed something that many constructivists would find uncomfortable: pupils could recall definitions perfectly in tests but revert to everyday ideas in real situations. They could reproduce a formula but not think with it. This gap between school learning and true assimilation revealed the constant conflict between scientific concepts and the ordinary concepts used by children outside school. Sometimes spontaneous knowledge competes with school knowledge; sometimes they coexist, with pupils mobilising academic knowledge for examinations but continuing to use previous associations in natural contexts.

One reason for this gap is that concrete content is often an obstacle to the assimilation of academic knowledge. An experiment with a control group showed that the group receiving direct and abstract teaching succeeded better in solving exercises than the group that obtained strong empirical scaffolding during the lesson. Abstract learning made it possible to structure thought and to orient it toward the resolution of problems. These facts directly contradict Davydov’s proposal to place school students in problem situations where the solution bypasses the formulation of an abstract principle. According to Menchinskaia’s research data, this does not facilitate learning but makes the problem situation increasingly complicated.

Abstraction, not concreteness, turned out to be the key. In one study, students who received abstract explanations solved more problems than those who had been taught through concrete examples and manipulative aids. Menchinskaia concluded that conceptual learning involves a two-way movement: “from the object to the word and from the word to the object”, abstraction and concretisation working together. Discovery learning, she warned, risked leaving students stranded in the concrete. The assimilation does not go from the top to the bottom but follows a complex path, with movement happening simultaneously in two opposite directions.

Her research focused specifically on the distinction between scientific concepts and ordinary concepts, the very distinction Davydov rejected. The whole meaning of her work was to understand how to take into account the daily experiments of children in school activities, to discover the laws of thought activity conditioned by the contents of the taught material. Her endeavour was the opposite of Davydov’s; it was rooted in the transmission of knowledge, in understanding how teaching transforms thinking.

Vygotsky Unbound

In 1936 the Central Committee of the Communist Party issued a decree condemning “pedology,” an emerging field that sought to integrate psychology, biology, and education; the very interdisciplinary framework Vygotsky had helped to establish. The decree denounced pedology as “antiscientific” and “anti-Marxist,” accusing it of treating children as objects of measurement rather than as products of socialist education. Because Vygotsky’s work had been central to this movement, the ban effectively buried his legacy. His books were removed from libraries, citations were censored, and his students were forced to distance themselves publicly from his name.

For nearly two decades, Vygotsky’s ideas survived only in underground circulation, mimeographed lecture notes, samizdat manuscripts, whispered references among trusted colleagues. Luria later recalled that during the late 1930s and 1940s, one could not mention Vygotsky’s name in print. His theories of the “higher psychological functions” and the “historical-cultural” formation of mind conflicted with the official doctrine that consciousness was a simple reflection of material conditions. Even his emphasis on language as a mediating tool, one of his most original insights, was politically dangerous in a climate that demanded slogans, not speculation.

It was only after Stalin’s death in 1953 and the subsequent thaw under Khrushchev that Vygotsky’s work began to re-emerge. His Collected Works were finally published in the Soviet Union between 1956 and 1984, and by the 1960s his students were able to discuss him openly again. Yet by then, much of his writing had been heavily edited to align with Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy, and entire sections, particularly those that dealt with religion, art, or freedom, remained unpublished.

The ultimate truth about Vygotsky’s life however, is that it was tragically cut short at a young age and haunted by fragility while he was alive. From an early stage he suffered from tuberculosis, a disease that recurred, interrupted his work, and fundamentally constrained his life span. He endured hospital stays, one drawn-out interval from late 1925 to 1926, and periods when he was declared incapacitated or invalid. Even as illness intruded, he continued to work intensely, writing essays, notebooks, and experiments, often under pressure and time constraints. His final years were marked by relentless intellectual urgency, as though he sensed time slipping away.

Colleagues remembered him as intensely energetic, restless, always reading, writing, speaking, forging connections. In An Intellectual Biography, Anton Yasnitsky frames Vygotsky’s life as a tension between urgency and limitation: his disease imposed boundaries on his time, yet he pressed against them ceaselessly.

Above all Lev Vygotsky was a family man. Despite the frenetic pace of his professional life and the constant shadow of tuberculosis, Vygotsky was remembered by his family as a loving, warm, and highly present figure. His daughters, Gita and Asya, later recalled their home life as being steeped in the same intense intellectual curiosity that defined his work.

Vygotsky often incorporated detailed, informal observations of his own children’s behavior and language acquisition into his research. His home was, in a sense, his first laboratory. His daughter, Gita, specifically recounted the warm, playful atmosphere, confirming that the Vygotskian emphasis on play as the “leading source of development” was rooted in his own experience as a parent.

His marriage to Roza, who moved with him to Moscow in 1924, was one of mutual support and shared intellectual purpose during a turbulent political era. The image of Vygotsky as a man who valued “interpsychological” interaction above all else was not merely a theory; it was a reflection of his own profoundly social family life.

Recent archival work offers a glimpse of the Vygotsky almost no one reads: a philosopher of freedom, emotion, and meaning. Andrey Maidansky’s analysis of Vygotsky’s notebooks shows that his final project, The Teaching about Emotions, was not about cognition or scaffolds at all. It was about liberation. “Freedom,” Vygotsky wrote, “is the affect in the concept”; the moment when emotion becomes intelligible, when feeling and reason fuse .

In his last major work he envisioned what he called a “height psychology”: a study of how consciousness can shape life, culminating in art, where reason and emotion achieve harmony. This Vygotsky was less an educational technologist than a moral philosopher of the human mind.

A poor translation of himself

The Vygotsky of today’s teacher training programmes died in 1934, was resurrected in California in 1978, and has lived ever since as a poor translation of himself. He has become an authority cited in support of pedagogies he might not have recognised, a name invoked to validate practices that contradict the core of his theoretical commitments.

Perhaps this is the fate of all influential thinkers; to be simplified, adapted, made useful in contexts far removed from their original concerns. But in Vygotsky’s case, the transformation has been particularly consequential. It has given a particular kind of minimally guided instruction a theoretical foundation that appears more solid than it actually is, and it has obscured an alternative vision of teaching, one that takes instruction seriously as the engine of intellectual development.

As Yvon, Chaiguerova, and Newnham note, Vygotsky’s writings must be read and re-read if we are to recover what he was really arguing for. His legacy has been mediated through translation, ideology, and fashion, leaving us with a theorist who is both everywhere and scarcely understood. To read him again is not an academic exercise, it is a way of reclaiming a vision of teaching as the engine of development rather than its echo.

Postscript: I just found this story by Vygotsky’s eldest daughter, remembering her father some 60 years after his death, which I think says more about the man he was than anything else written about him:

There is one more thing that happened that I will recount. It’s still unpleasant to talk about it, but it happened and it taught me a lesson for life. By now I was in school. I remember it was late May. In class we had an important final coming up. I had a very serious attitude toward it, and was rather anxious. It so happened that I did well on the exam and got a high mark. I returned home in high spirit and was doubly over joyed: my father was home! When he asked me what was new in school, I proudly told him of my success, and added with ill-concealed pleasure that the girl sitting next to me could not copy from me as I had turned the page of

the notebook, and because of this got a poorer grade than me. I was beaming and expecting praise, looked at father. I was surprised at the expression on his face: he looked very disappointed. I could not understand what was wrong. May be he did not realize I passed?After a short silence he began to speak, slowly and deliberately so I would remember everything he said. He told me that it was not nice to be happy of others misfortunes, that only selfish people enjoyed it. He went on saying that I should always try to help those who need it, and it’s only for those who help others that the life is rewarding and brings true joy. I remember I was very upset from his words and asked what I should do now.

As always in these situations he offered me a solution: he did not want me to feel like once I did something wrong I was now incapable of doing good. He suggested to me that I go and ask my classmate about what she didn’t understand, and try to patiently explain it to her, and if I couldn’t do it so she would understand perfectly, then he would be glad to help me. “But here is the most important thing”, he added, “you must do all this so your friend be sure you really want to help her, and really mean her well, and so it would not be unpleasant for her to accept your help”. More than 60 years have passed since this incident and I still remember all of his words and try to follow them as best I can in life.

Yvon, F., Chaiguerova, L. A., & Newnham, D. S. (2013). “Vygotsky under debate: Two points of view on school learning.” Cultural-Historical Psychology, 9(4), 52–62.

M. Cole, “Prologue,” in The Essential Vygotsky, ed. Robert W. Rieber and David K. Robinson. New York, NY: Springer US, 2004, p. xi.

Cole, M. (1996). The perils of translation: A first step in rethinking Vygotsky’s theory and methodology. In H. Daniels (Ed.), An Introduction to Vygotsky (pp. 1–24). London: Routledge.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1934/2012). Le problème de l’apprentissage et du développement intellectuel à l’âge scolaire [The problem of training and intellectual development at school age]. In F. Yvon & Y. Zinchenko (Eds.), Vygotsky, une théorie du développement et de l’éducation [Vygotsky, a theory of development and education] (pp. 221–247). Moscow: Moscow State University.

For any work-related enquiries, contact me here.

Well--as a Californian in a teacher-training program in the 80's, I was steeped in Vygotsky but lucky to have been given this interpretation: "His classroom centres the teacher as the one who introduces learners to forms of thought they could never reach alone. Knowledge is not discovered but revealed through explicit, structured instruction. The teacher does not step back; the teacher steps in." (Love that stepping back vs. stepping in image!) And when decades later Tim Shanahan warned against using guided reading groups at a student's so-called 'instructional level' in favor of whole-class instruction with challenging grade-level text, it led me back to my training. My role was clear: "not only do children develop but also we adults develop them”. Thanks for this illuminating deep dive!

This is a revelation to me thanks to it's clarity of style and demonstration of a true Vygotskian learning process. Brilliant!