Ultra-Processed Minds: The End of Deep Reading and What It Costs Us

A reflection on the reading life. What formed it, what threatens it, and what remains.

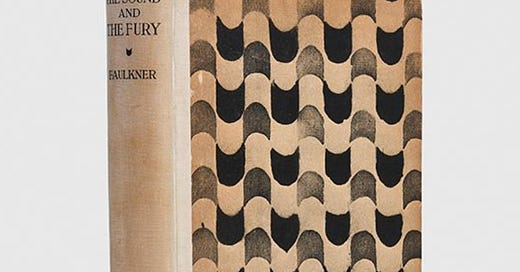

I have a vivid memory of reading a particular book. A book that in hindsight, shaped my adult reading habits perhaps more than any other. It was the summer of 2003, and I was assigned William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury for a college course. The first 50 pages were dense, impenetrable, and unforgiving. Written in a fragmented, stream-of-consciousness style from the perspective of Benjy, a cognitively impaired character whose sense of time and narrative coherence is profoundly disordered, the book asks much of the reader.

I remember feeling lost, even resentful. Rereading passages multiple times without understanding. There was no clear narrative thread, no obvious meaning to grasp, only confusion. But at some point, something shifted. I became attuned to the book’s tone, internal rhythm and emotional undertow. Gradually, the fog began to lift. Patterns emerged, connections formed, and I realised that the disorientation I felt was the whole point: Faulkner was immersing me in a mind for whom disorientation was their reality.

I read the rest of the book over a period of two days in a kind of fever dream. The difficulty of the text had induced a kind of trance that came from a sustained focus even an obsession. I remember finishing the last page and reeling from the book’s harrowing final chapter. That encounter became a powerfully instructive moment for me in what reading could be; demanding, disorienting, but ultimately transformative. It required me to relinquish control, to dwell in uncertainty, to read not for a plot I expected but for a kind of negative capability. It was, in a very real sense, a kind of apprenticeship in cognitive patience: the willingness to wait, to trust that meaning would reveal itself, not all at once, but gradually, obliquely.

I recall that experience today somewhat wistfully, in an unrecognisable age where so little of what we read asks anything of us. The idea of lingering with a text that doesn’t yield immediate meaning feels increasingly alien today. In a world shaped by feeds and fragments, where comprehension is measured in clicks and content must gratify instantly or be discarded, a book like Faulkner’s feels almost impossible.

I read to my 6 year old and 4 year old daughters every night and I worry what kind of reading life they will have. I know it will be fundamentally different to mine but what I fear they’ll miss is not literature’s beauty but its resistance. The way it trains the mind to slow down, to reflect, to tolerate ambiguity. To reside in the discomfort of the interstitial and be ok with it. The way it sharpens perception by refusing to simplify. The world they are entering is freighted with superficiality and false certainty with its Blinkist-ification and summaries of summaries and algorithmic banalities. As Baudrillard put it, copies of copies of which we have now lost the original.

Ultra-processed reading

We live in an age of lexical abundance. More words, more access, more content than at any time in human history. And yet something essential is slipping away. Not reading itself, but the kind of reading that once shaped minds and formed character: slow, immersive, reflective, and richly human. As Harold Bloom noted: “"We read deeply for varied reasons, most of them familiar: that we cannot know enough people profoundly enough; that we need to know ourselves better."1

In its place, we are cultivating habits of skimming, scanning, and superficial intake. Modes better suited to consuming than to understanding. This is not merely a shift in preference; it is a rewiring of cognition. The reading brain, once forged by sustained attention and deep engagement, is now adapting to an environment built for speed, distraction, and artificial fluency. What we are witnessing is not the end of reading, but rather the end of the essential consolations that reading affords us. Reading, but in ultra-processed form.

Not all reading is created equal. Just as not all food nourishes, not all content feeds the mind. In the age of platforms and prompts, of AI authors and infinite feeds, we are reading more but understanding less. What we consume is increasingly pre-digested cognition: engineered for ease, stripped of its vital ambiguity, void of risk. Ultra-processed reading is syntactically smooth, cognitively shallow, emotionally inert. This isn’t just about TikTok or Twitter. It’s about how the medium reshapes the mind, how digital habits dull our appetite for complexity, and how a civilisation that forged itself through the long-form written word might forget what it means to think.

Reading is not natural. It is an acquired skill, hard-won, an evolutionary detour that turned the human brain into a space for rarefied thought; reflection, argument, imagination. And yet, in a digital culture of continuous partial attention, this capacity is undoubtedly slipping from us. What was once a labour of immersion is now a reflex of distraction. The words haven’t vanished, but the reader has changed. This shift from deep reading to shallow skimming, from authored insight to algorithmic noise is no accident. It is the product of platforms, of incentives, of a technological ecology indifferent to meaning. To understand what we are losing, I feel we should begin by noticing how we now read and why it no longer resembles reading at all.

Reading in Decline

One of the finest things I ever heard uttered in my life was by a seasoned teacher who taught in the classroom next to me for many years. Once when asked by a student why they should read Shakespeare, he replied that the plays are “an anthropological guidebook which tells us how to live.” That was 10 years ago and its obvious to me now that they way in which students read Shakespeare today has fundamentally changed, even in the last 18 months with the advent of Large language models. How many students would now sit with a copy of Lear underlining strange words and phrases and seeking to marry this new knowledge with what they already know? Struggling with the enormity of the language and the vastness of its meaning.

The numbers are unambiguous. According to US federal data analysed by Sunil Iyengar of the National Endowment for the Arts, reading for pleasure is in steep decline across every age group in the United States. Most dramatically, the drop is concentrated among young adults, a generation being raised on infinite scroll and ambient distraction. This is not a gentle tapering, but a cultural inflection point. People are reading more words, but fewer books and as a result, they’re reading in an increasingly shallow way.

The distinction is crucial. What we are seeing is not less exposure to text, but a fundamental shift in the nature of that exposure. The immersive arc of narrative is giving way to the skimmable feed. Syntax shortens, attention fractures, the very architecture of thought begins to mimic the medium. In such a climate, the deep literacy once nurtured by novels, essays, and reflective prose becomes harder to cultivate, and perhaps harder to desire.

But the costs of this shift are not merely literary or aesthetic. They are cognitive, emotional, and civic. Students who read for pleasure consistently perform better on academic assessments and not just in English, but across disciplines. Reading deeply strengthens the capacities that underlie all learning: memory, inference, comprehension, and sustained attention. Beyond academic attainment, regular readers report higher measures of emotional wellbeing, greater empathy, and a stronger sense of social connection. In other words, reading is not simply a leisure activity, it is a foundational habit of mind, one that supports both inner coherence and outward understanding.

The cognitive casualty of this new diet is our capacity for sustained attention, nuanced comprehension, and deep reflection. Trained by fragmented inputs and rewarded for speed rather than depth, the mind becomes conditioned to expect ease, immediacy, and constant stimulation.

To lose this habit at a societal scale is not a small thing. It is to unmoor ourselves from the slow, accretive processes that form character, judgment, and self-knowledge. A culture that stops reading deeply does not merely lose its stories, it risks losing the very tools by which it interprets them. Reflection, nuance, ambiguity, these are not incidental by-products of reading. They are its gifts. And as they fade, so too does our capacity to meet the complexity of the world with anything other than reaction.

What we read when no one is writing

If reading is being reshaped by digital habits, then so too is the content itself which is of the ultra-processed form: flattened, filtered, stripped of its essential intellectual nutrition and increasingly produced not by humans at all, but by algorithms. Where once content was the expression of an inner life, now it is often designed to catch a query. Short-form, SEO-optimised, and emotionally neutered, much of what passes for writing today is tailored not for the attentive reader but for the indifferent algorithm. Its purpose is not to reveal, disturb or nourish, but to rank.

This is not merely a change in medium, but a shift in intention. Where the essay once aspired to complexity, now the imperative is superficial clarity at all costs. Where literature once trafficked in ambiguity, today’s digital prose prizes fatuous utility. Even the rhythms of language are changing: from paragraphs to bullet points, from subtext to mere scannability. What matters is whether the keyword appears in the first hundred words. not whether the sentence carries any weight of thought.

As content becomes more engineered than written, AI has stepped into the role of ghostwriter; fluent but fatally hollow. Tools like ChatGPT and its cousins can produce grammatically perfect, tonally inoffensive copy at scale. What they lack, of course, is experience. They have no stake in what they say. Their fluency is not expression, but simulation. They reheat the language of others with no memory of heat. As Ted Chiang puts it, large language models are “blurry JPEGs of the web”; articulate without awareness, derivative without depth.

This matters. Not because machines are writing, but because we are beginning to write like them. Predictability has become a virtue. Voice is flattened into tone. Style is reduced to format. And behind it all is a new kind of anonymity and not the anonymity of the humble author, but the anonymity of the absent one. In the glut of generated content, no one really speaks. No one risks themselves on the page.

Sherry Turkle has written extensively on the consequences of this shift. In Reclaiming Conversation, she argues that digital communication encourages performance over presence: we craft ourselves not to connect, but to be seen. The result is what she calls “the edited self,” curated for likes, detached from genuine reflection. In place of inner life, we have brand management. In place of thought, performance.

Sven Birkerts warned of this in The Gutenberg Elegies, lamenting the loss of “the language of inwardness.” As the screen displaces the page, he argues, we risk becoming strangers to our own interiority. “Writing, in its essence,” he reminds us, “is an intimate, recursive act, an engagement with thought that deepens it.” But in a culture saturated with artificial content and algorithmic curation, intimacy becomes noise, recursion becomes redundancy, and thought becomes just another asset in the content economy.

The tragedy is not that we are reading less, but that we are being fed more, and that what we are fed no longer expects much from us anymore. It demands clicks, not contemplation; affirmation, not argument. It asks us to skim, to share, to move on. In doing so, it erodes not only our attention, but our appetite for complexity, for difficulty, for truth. The reader is no longer a co-creator of meaning, but a consumer of impressions. In such a system, the very possibility of serious thought begins to look anachronistic.

Cognitive Patience

Maryanne Wolf introduces a subtle but urgent concept into the discourse on reading: cognitive patience. It is, at heart, the willingness to linger in difficulty. The capacity to stay with a complex sentence, a knotty idea, a layered argument long enough for meaning to emerge. This kind of patience was once cultivated by the reading of dense, syntactically rich texts, the very kind of literature, philosophy, and essay-writing that formed the backbone of humanistic education. Today, that patience is faltering, not because students are less capable, but because the reading environments they inhabit train them in the opposite direction.

Wolf’s concept of cognitive patience helps name a phenomenon central to the decline of meaningful discourse. We are not merely losing our capacity for deep reading, we are losing our tolerance for the conditions under which deep thought becomes possible. In the absence of this patience, complexity is not engaged, but avoided. Ambiguity is not tolerated, but dismissed. We become allergic to intellectual difficulty, not because it is beyond us, but because we have forgotten how to sit with it.

This is the crisis of complexity. And its implications are far-reaching. A society that can no longer read complex texts may soon find itself unable to think complex thoughts or to recognise when they are missing. In that context, reading becomes not just a cognitive act, but a civic one: a rehearsal for the intellectual stamina that democracy requires.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Reading

One of the most potent frameworks for understanding our current reading crisis comes from Sven Birkerts, extended and refined by Mairead Small Staid in her essay Reading in the Age of Constant Distraction. Drawing on historian Rolf Engelsing, they describe a cultural shift in how we read—less a decline than a reorientation. We are moving from what Birkerts calls “vertical” reading: deep, devotional, recursive engagement with a single text, toward “horizontal” reading: skimming, browsing, grazing across sources, surfaces, and screens.

Vertical reading is immersive. It asks something of us, namely time, attention, vulnerability. It allows meaning to accumulate and resonate. Horizontal reading, by contrast, privileges motion over meaning, exposure over absorption. It is the cognitive equivalent of scrolling a buffet table: a little here, a little there, but rarely a full meal. As Staid puts it, “The deep, devotional practice of ‘vertical’ reading has been supplanted by ‘horizontal’ reading, skimming along the surface.”

Just as ultra-processed food is engineered for convenience and immediate reward rather than nourishment, so too is the content we increasingly consume: short, simple, emotionally legible, and optimized for rapid ingestion. We don’t dwell in it, we move through it. We are constantly full, but rarely fed.

The shift is not merely stylistic. It has consequences for how we think, how we feel, and how we come to know the world. Vertical reading cultivates depth; of thought, of empathy, of interiority. Horizontal reading rewards speed, novelty, and cognitive lightness. One forms a self. The other disperses it.

In Stand Out of Our Light, James Williams introduces the notion of “adversarial design” to describe the way digital technologies increasingly work against, rather than for, the user’s best interests. Unlike traditional tools that extend human agency, these systems are engineered to exploit our cognitive vulnerabilities, hijacking attention, nudging behaviour, and diverting us from our higher-order goals. They do not serve our intentions but subvert them, optimising instead for metrics like time-on-site, clicks, and engagement. The result is a form of design that is not neutral but strategically manipulative: a slot machine disguised as a compass. In privileging persuasive architecture over meaningful use, adversarial design erodes the very autonomy it pretends to enhance.

Reading as Resistance

I had a difficult adolescence. Struggling with the early strains of mental health issues that I would later forge into some semblance of awkward identity, I found solace in books and music. Much to my parents concern, I would spend hours in my room reading whatever I could get my hands on. From the vantage of these years, I can see now that this was about asserting myself in a world in which I had little control. Reading for my adolescent self was a form of tacit resistance. It was a way of imposing a kind of order on the increasing chaos of my teenage mind.

To read slowly, attentively, without agenda or distraction is to resist. Not with noise or spectacle, but with the quiet, deliberate force of contemplation. In an economy built on speed and stimulus, deep reading becomes an act of principled refusal. It defies the algorithm’s logic of efficiency, the newsfeed’s velocity, the platform’s hunger for engagement. It says: I will dwell here, I will think for myself, I will go deep when the world wants me shallow.

To read in this distracted age is therefore to make a moral and political choice. It is, as Sven Birkerts put it, to defend “the private self,” that fragile interiority born of silence, solitude, and sustained thought. It is to reclaim what Walter Benjamin called the “aura” of experience; the depth and duration that resist flattening by mechanical reproduction. We must create sanctuaries for such reading, not out of technophobia, but out of care for what kind of minds, and what kind of citizens, we are shaping.

The alternative is not just a diminished literacy, but a diminished self: a culture that feeds on fragments and forgets what it once meant to know. Not only what the author intended, but what the reader might become. As Proust once wrote, the truest books are “mirrors” in which we discover not the writer’s wisdom, but our own. If we lose the capacity to pause and reflect, we do not merely lose our stories, we lose the space in which to make sense of them.

As I write this, now I wonder what would have happened if I’d been reading The Sound and the Fury on a screen with notifications, tabs, distractions, and the frictionless temptation to give up and Google a summary or even to use chatGPT to write the essay I had to produce on the book, a piece of writing in which I deliberated over every word. Would I have stuck with it? Would I have persevered through the ambiguity? In the summer of 1933, some 80 years before I read his novel, Faulkner wrote:

I wrote this book and learned to read. I had learned a little about writing from Soldiers' Pay--how to approach language, words: not with seriousness so much, as an essayist does, but with a kind of alert respect, as you approach dynamite; even with joy, as you approach women: perhaps with the same secretly unscrupulous intentions. But when I finished The Sound and The Fury I discovered that there is actually something to which the shabby term Art not only can, but must, be applied. I discovered then that I had gone through all that I had ever read, from Henry James through Henty to newspaper murders, without making any distinction or digesting any of it, as a moth or a goat might. After The Sound and The Fury and without heeding to open another book and in a series of delayed repercussions like summer thunder, I discovered the Flauberts and Dostoievskys and Conrads whose books I had read ten years ago. With The Sound and The Fury I learned to read and quit reading, since I have read nothing since. 2

Bloom, Harold. How to Read and Why. New York: Scribner, 2000, p. 19.

https://drc.usask.ca/projects/faulkner/main/criticism/morrison.html

Fantastic piece that resonates very deeply with me. It feels like there is a fundamental tension between modern life and the quiet contemplation that comes along with deeply engaging in great books.

Over the last several years, I've made a concerted effort to minimize distraction as much as possible, but it's something I need to constantly fight against. There are always notifications buzzing, new shows on Netflix, and tweets or Instagram posts that my friends text me, each trying to grab hold of my attention. I've taken to blocking as much functionality of my phone as I can, disabling all social media apps and preventing myself from download any new apps. It has worked fairly well, but I can't help but feel that my attention is still more fractured than I would like it to be.

Hi Carl---excellent post! As an addendum, this opinion piece by Seth Bruggeman, a public history professor at Temple University in Philadelphia is very much worth the time--about halfway through (after addressing the issues of rampant academic dishonesty) he says this:

"By far, though, the most striking and maybe most troubling lesson I gathered during our unconference was this: Students do not know how to read. Technically they can understand printed text, and surely more than a few can do better than that. But the Path A students confirmed my sense that most if not a majority of my students were unable to reliably discern key concepts and big-picture meaning from, say, a 20-page essay written for an educated though nonspecialist audience."

https://www.insidehighered.com/opinion/views/2025/01/14/crisis-trust-classroom-opinion#