The Paradox of Memory: Why Forgetting Makes Learning Possible

Borges, Bjork, and the science of memory, forgetting and learning

In Borges' short story Funes the Memorious, the protagonist is cursed with a perfect memory: every leaf on a tree, every fleeting sensation, every trivial detail is preserved. But this gift renders him incapable of thought. With nothing forgotten, nothing can be abstracted, compared, or made meaningful. Borges’ parable captures a profound truth about learning: memory is powerful not because it records everything, but because it forgets.

“He was the solitary and lucid spectator of a multiform, instantaneous and almost intolerably precise world.”

The attempt to preserve everything collapses under its own weight, because without pruning, nothing can be generalised or made useful. Forgetting, by contrast, is what allows us to compress, to prioritise, to abstract, and to find meaning in the mass of experience.

Borges plays with the idea of creating a language in which every single object and moment would have its own name, echoing Locke’s speculation about such an impossible system. But Funes abandons it when he realises that knowledge without forgetting is not knowledge at all, just an endless catalogue. To compare two things, two ideas, two experiences, we need them in some simplified form. If each is stored with every microscopic detail, there’s no way to align them, so they remain incomparable.

In computer science, this problem is familiar. A machine-learning model that memorises every data point performs flawlessly on the training set but fails to generalise to new situations, an error known as overfitting. Likewise, a database that stores only raw logs without indexes becomes impossible to search. Without some form of forgetting or compression, detail overwhelms meaning.

This story illustrates a fundamental paradox about memory and learning: Forgetting is what allows us to prioritise, to see patterns, to make knowledge durable. In Funes' overly replete world, there were "nothing but details, almost contiguous details." His perfect memory made thought impossible. Human thought depends on sifting, ignoring, pruning. Memory that records indiscriminately, like Funes’s, produces an unmanageable catalogue. The act of forgetting clears space for patterns to appear and for connections to form

The Science Behind the Paradox

I studied literature before I encountered the science of memory and am endlessly fascinated by how literature anticipated truths that would not be formally discovered until decades, sometimes centuries later. To my mind Shakespeare was the first true cognitive scientist, indeed as Bloom noted, Shakespeare's characters possess a psychological reality that exceeds even their creator's conscious intentions; they think and feel with a complexity that anticipates modern understanding of the mind.

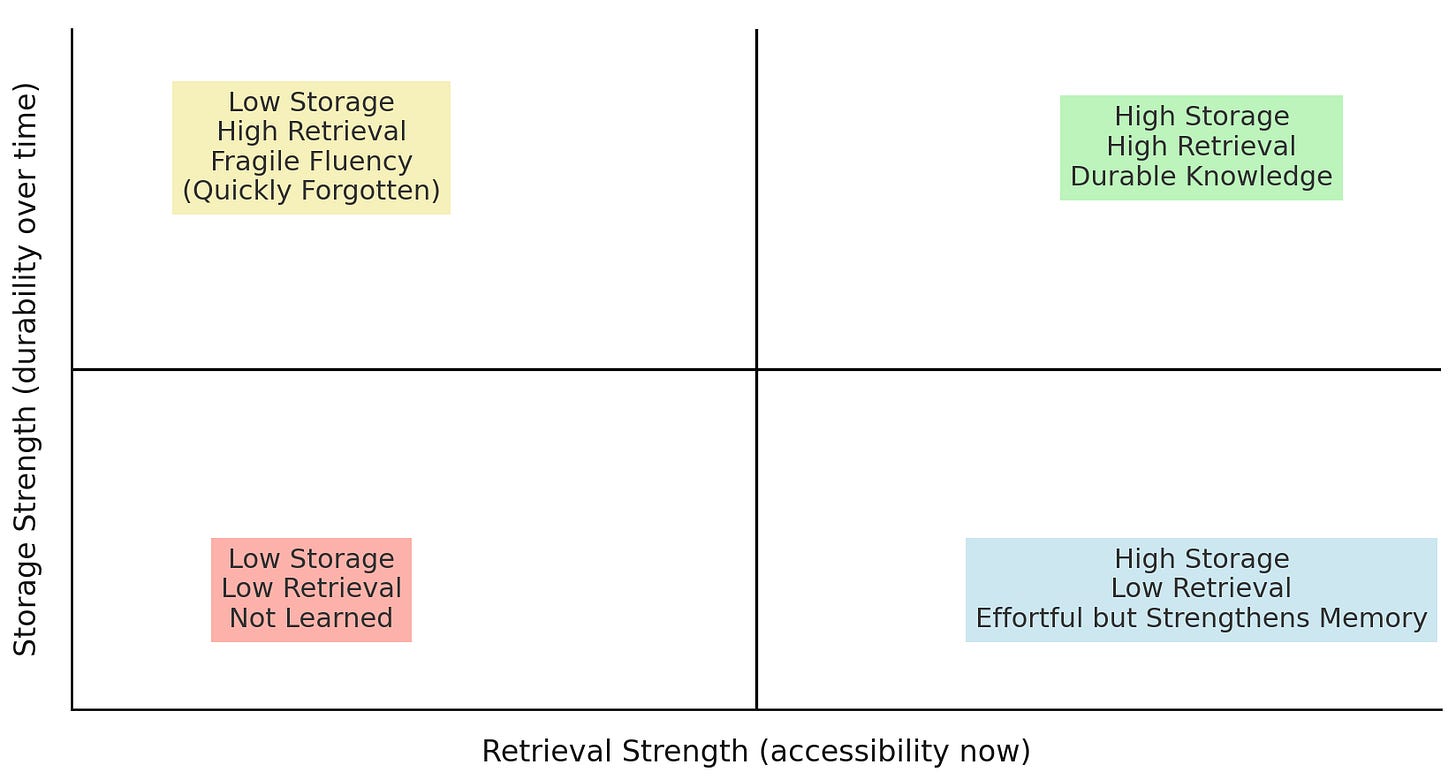

What Borges intuited about memory through fiction, Robert and Elizabeth Bjork explored through decades of research on memory and forgetting. Their "new theory of disuse" distinguished between two types of memory strength: retrieval strength and storage strength.

A fact can feel inaccessible in the moment (low retrieval strength) but still be deeply encoded (high storage strength). Crucially, each successful act of effortful retrieval increases both. That is why the temporary forgetting we experience between practice sessions actually enhances learning.

It also illustrates why rereading a page may feel fluent in the moment but produces only short-lived gains: it boosts retrieval strength briefly without adding much storage strength. In contrast, testing yourself on that same material, even if you fail at first, creates the conditions for storage strength to grow. Effort, not ease, is the signal of long-term learning.

The Bjorks coined the term “desirable difficulties” to capture this counterintuitive truth. Strategies such as spacing out study sessions, interleaving topics, and varying practice conditions slow performance in the moment but yield more durable and flexible knowledge. In other words, the very conditions that appear to impede learning actually secure it.

Consider two students preparing for an exam. One crams the night before, achieving high retrieval strength but little storage strength. The other spaces their practice over weeks, encountering repeated moments of forgetting followed by effortful recall. On test day, the crammer may outperform in the short term, but months later, it is the student who embraced forgetting and retrieval who still remembers.

The Retrieval Effect: Why Testing Works

This neatly explains why testing is so powerful for learning and why the Bjorks described testing not just as a test of learning but as a learning event itself. When we struggle to recall information from memory, we're not just assessing what we know, we're actively strengthening the memory trace. Each act of effortful retrieval makes the information more likely to be retrieved again in the future.

The irony is that the methods that produce the most immediate fluency such as re-reading, highlighting, immediate review, often create the illusion of learning without building lasting retention. Students feel confident because information is readily accessible in working memory, but this accessibility is temporary. The moment the external cues disappear, so does the knowledge.

This is why regular low-stakes testing, quizzes, or even self-questioning can be so effective. Each retrieval attempt, even if it fails, signals to the brain that the information matters and should be reinforced. Feedback then closes the loop, turning errors into learning opportunities. In practice, this means that the best way to prepare for an exam (or to learn anything deeply) is not massed review before performance but repeated, spaced attempts to recall, each one strengthening the trace and making future retrieval more reliable.

Forgetting as Adaptive Function

The Bjorks’ work reveals that forgetting isn't a failure of the memory system, it's an adaptive feature. Our brains are constantly making decisions about what deserves long-term storage. Information that gets repeatedly retrieved and used is marked as important and strengthened. Information that sits unused gradually becomes less accessible, freeing up cognitive resources for more relevant knowledge. As Benjamin Storm notes: "Without some means of forgetting information that has become outdated or irrelevant, it would be incredibly difficult to remember information that is relevant."1

This selective forgetting is what allows us to function in a world of infinite information. Without it, we would indeed become like Funes, paralysed by the weight of accumulated detail, unable to see patterns or make meaningful connections.

The Bjorks describe this as the memory system's "contextual variability", in other words, our ability to adapt what we remember based on what we need. Memory isn't a passive storage system but an active, intelligent filter that responds to our changing environment and goals. When we stop using certain information, the system interprets this as a signal that the information is no longer relevant and allows it to fade.

This process becomes even more sophisticated when we consider that forgetting operates at multiple timescales. Some information like where you parked your car today, needs to be forgotten quickly to avoid interference with tomorrow's parking location. Other information like your childhood address, might fade gradually over decades unless actively maintained through retrieval.

The system is also remarkably sensitive to context and competition. The Bjorks' research on "retrieval-induced forgetting" shows that when we strengthen some memories through practice, we can actually weaken related but competing memories. This isn't a design flaw, it's a feature that helps us maintain coherent, updated knowledge by suppressing outdated or competing information.

Perhaps most importantly, this adaptive forgetting creates the conditions for abstraction and generalisation. By allowing specific details to fade while preserving general patterns, our memory system enables us to extract principles, recognise similarities across different contexts, and apply knowledge flexibly. We don't need to remember every specific instance of addition we've ever performed; we need the abstract principle that allows us to solve new addition problems.

This is why Borges' Funes, cursed with perfect recall of every detail, cannot think abstractly. His memory lacks the crucial capacity for selective forgetting that would allow him to move beyond the specific to the general, beyond the particular to the pattern. In trying to preserve everything, his memory preserves nothing useful.

The adaptive function of forgetting reveals memory's true purpose: not to create a perfect record of the past, but to build a useful foundation for the future.

The Lesson of Funes: Why Forgetting is the Key to Abstraction

Far from being the enemy of memory, forgetting then is what makes memory possible. If we remembered everything equally, nothing would stand out. Memory works by filtering, not stockpiling. That is why tests are not just assessments of learning but powerful vehicles of learning: each act of effortful retrieval changes the system, raising both retrieval and storage strength.

In the end, we return to Funes, trapped in his prison of perfect recall. Borges understood what cognitive science would later prove: that Funes couldn't think because he couldn't forget. Every moment remained equally vivid, every detail equally present, every memory competing for attention in an endless, undifferentiated stream.

Funes saw everything but understood nothing. As Borges put it, he suffered from an “incapacity for general, platonic ideas.” Understanding requires comparison, and comparison requires zooming out and to some extent, forgetting the infinite catalogue of differences. To know that two events are similar, we must forget their unique details and focus on their common features. Funes, cursed with total recall, could never make such comparisons. Every experience remained utterly distinct, incomparably itself. In the end, Funes reminds us that memory endures because it filters, not because it hoards. Forgetting is the price we pay for understanding, and the reason learning is possible at all.

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In A. F. Healy, S. M. Kosslyn, & R. M. Shiffrin (Eds.), From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes(Vol. 2, pp. 35–67). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Borges, J. L. (1962). Funes the Memorious. In Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings (D. A. Yates & J. E. Irby, Trans.). New Directions Publishing. (Original work published 1942)

Storm, B. C. (2011). Retrieval-induced forgetting and the resolution of competition. In A. S. Benjamin (Ed.), Successful remembering and successful forgetting: A Festschrift in honor of Robert A. Bjork (pp. 89–108). New York: Psychology Press.

This is such a superb piece. Clear, nuanced, and beautifully written. One of the best treatments of memory and forgetting I've come across!

While reading this, a few thoughts came in. First, about the difference between episodic memory and semantic memory. Without being able to "forget", we are constantly stuck with episodic memories and cannot form any meaning (semantic memories).

Another one was from NLP (Neuro Linguistic Program) concept. I know NLP sounds scammy but some concepts are helpful. Like, the idea of how our brain goes through Deletion, Distortion, and Generalization of our experiences. As a result, everyone has a different maps or mental models of the same territory.

This was a great read. This one "Memory isn't a passive storage system but an active, intelligent filter that responds to our changing environment and goals. When we stop using certain information, the system interprets this as a signal that the information is no longer relevant and allows it to fade." makes so much sense.