Why The Forgetting Curve Is Not As Useful As You Think

Ebbinghaus' research was groundbreaking for the time but it's not really how learning happens in authentic learning situations

I see a lot of training where school leaders/trainers use Ebbinghaus as a vehicle to talk about retrieval practice and while the basic premise is important and interesting, I don’t think it’s particularly useful for teachers. I mentioned this in a talk recently and someone asked me to explain it in more detail so here it is.

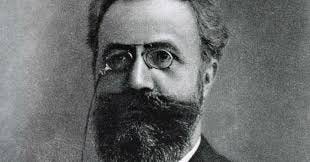

In 1876 Ebbinghaus discovered a used copy of Fechner's Elements of Psychophysics. Inspired by Fechner's mathematical rigour, Ebbinghaus decided to apply similar experimental and quantitative methods to the study of human memory, an area that had previously been explored only through philosophical speculation rather than systematic investigation. (At this time phrenology was still a respectable scientific theory.)

Determined to scientifically measure how memories form and fade over time, he conducted self-experiments using nonsense syllables (e.g., "WID," "ZOF") to eliminate pre-existing associations, allowing him to isolate pure memory processes. This work led to the formulation of the forgetting curve, the learning curve, and foundational principles of spaced repetition, which continue to shape cognitive psychology and education today.

His famous study gave us key insights into the rate at which information is forgotten over time without reinforcement. The forgetting curve demonstrated that memory loss follows an exponential pattern; most forgetting happens soon after learning, with the rate of loss slowing over time. This insight reinforced the importance of spaced repetition, showing that revisiting information at strategic intervals could dramatically improve retention.

However, while these findings are often linked to retrieval practice in education, the connection is not as straightforward as some suggest. Ebbinghaus’ experiments focused on the passive memorization of meaningless syllables and primarily makes claims about memory decay, but memorising trigrams devoid of semantic content is not really how we learn in authentic learning environments.

The Problem with the Forgetting Curve

The curve assumes a uniform rate of decay, but subsequent research suggests that forgetting is highly variable and context-dependent. For example, knowledge that is well-integrated into prior schemas is far more resistant to forgetting (Sweller, van Merriënboer, & Paas, 2011). This is why spaced repetition works best when combined with meaningful retrieval rather than rote exposure.

Ebbinghaus's experimental design was actually quite brilliant in terms of the methodology to isolate memory as a sort of mechanical function stripped of contextual variables. But real learning is not about memorizing nonsense words. We don’t store and retrieve information in a vacuum. Rather, they operate within richly interconnected networks of significance, contextual embedding, and pre-existing frameworks of meaning.

Memory Works Semantically, Not Veridically (mostly)

Frederic Bartlett's groundbreaking work Remembering (1932) demonstrated that memory functions not as exact reproduction but as an active reconstruction. His research revealed that when we remember, we don't simply retrieve perfectly preserved information; instead, we rebuild memories in ways that align with our existing understanding of the world. (Paul Kirschner and I covered this in chapter 4 of How Learning Happens 2nd edition) We don’t remember things exactly as they were; we remember them in ways that make sense to us. When we learn, we integrate new information into what we already know, shaping it to fit our existing knowledge structures.

This insight was further developed by David Ausubel, who argued that meaningful learning occurs when new information connects with prior knowledge. Unlike Ebbinghaus’s artificial experiments, Bartlett and Ausubel demonstrated that memory is not about storing disconnected facts but about integrating information into a web of understanding. On this topic, I am always reminded of Dan Willingham’s wonderful phrase: “Understanding is remembering in disguise.”

Interference vs. Decay: McGeoch, Thorndike, and Bjork on Forgetting

Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve suggests that memories fade passively over time, but later research challenges this, showing that forgetting is often due to interference rather than simple decay. John A. McGeoch (1932) argued that time itself does not cause forgetting; rather, new learning interferes with old learning, making some memories harder to retrieve. This explains why students struggle to recall concepts—not because they have decayed, but because similar information competes for retrieval.

Edward Thorndike’s early Theory of Disuse proposed that memories fade when not used, but this was later refined by Robert Bjork’s New Theory of Disuse, which distinguishes between storage strength (how well a memory is embedded) and retrieval strength (how accessible it is at a given moment). While storage strength remains intact, retrieval strength weakens with disuse but can be restored through retrieval practice. This means forgetting is not permanent loss but temporary inaccessibility. Unlike Ebbinghaus’s model, which assumes a steady decline, Bjork’s research shows that retrieval, not just repetition, strengthens memory. This has profound implications for teaching: simply reviewing material is ineffective unless students actively retrieve it. The best way to prevent forgetting is not passive repetition but structured, effortful retrieval that strengthens long-term access to knowledge.

Wickelgren's (1972) Dual-Process Memory Theory presented a sophisticated framework that challenges simplistic views of forgetting. While Ebbinghaus conceptualized memory loss primarily as passive decay over time, Wickelgren demonstrated that forgetting emerges from at least two distinct mechanisms operating in tandem. The theory posits that memory attrition stems not merely from temporal deterioration but significantly from interference processes, wherein memories compete with one another. This competition manifests bidirectionally: proactive interference occurs when established memories impede the acquisition of new information, creating a cognitive inertia that resists novel learning; conversely, retroactive interference involves recently formed memories disrupting or reconfiguring previously encoded information, essentially rewriting our mnemonic landscape. This nuanced understanding reveals forgetting as an active, multi-faceted phenomenon rather than simply a failure of retention, a perspective that has profound implications for educational practice and cognitive enhancement strategies.

Why This Matters for Teaching

One of the things I’m a little obsessed with is lethal mutations of good research. “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing” as Alexander Pope said and in many ways, a misapplication of research is worse than complete ignorance of it. The forgetting curve implies that students lose knowledge at a predictable rate and that the solution is simply to reintroduce the same information at set intervals. But if learning is largely semantic rather than mechanical, then the most effective teaching strategies must focus on meaning-making and connection-building rather than rote memorisation of isolated, meaningless items.

Retrieval does more than prevent forgetting; it actually restructures knowledge, making it more accessible and adaptable. The effectiveness of retrieval is not just about repetition, but about depth. When students reconstruct knowledge in new contexts, they strengthen their ability to apply it flexibly. Roediger & Karpicke, are right when they say “Remembering is greatly aided if the first presentation is forgotten to some extent before the repetition occurs” but for meaningful learning, what matters is what remembering is connected to.

Simply re-exposing students to isolated, disconnected, information at spaced intervals is not enough; retrieval practice, elaboration, and interleaving are crucial in strengthening memory traces but work fundamentally in integrating knowledge into broader conceptual frameworks. Learning happens when students actively reconstruct knowledge, making connections to prior learning and applying it in varied contexts.

So while Ebbinghaus is the OG in terms of memory research, his work should not be taken as a comprehensive model for how learning actually happens in real-world classrooms. His research was crucial in identifying general trends in forgetting, but the process of learning is far more complex than simple decay over time.

Works Cited

Ausubel, D. P. (1963). The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. Grune & Stratton.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge University Press.

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In A. F. Healy, S. M. Kosslyn, & R. M. Shiffrin (Eds.), From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes(Vol. 2, pp. 35-67). Erlbaum.

McGeoch, J. A. (1932). Forgetting and the law of disuse. Psychological Review, 39(4), 352-370.

Sweller, J., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. G. W. C. (2011). Cognitive architecture and instructional design: 20 years later. Educational Psychology Review, 23(2), 261-292.

Thorndike, E. L. (1914). Educational psychology (Vol. 2). Teachers College, Columbia University.

Wickelgren, W. A. (1972). Trace resistance and the decay of long-term memory. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 9(4), 418-455.

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don't students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

I'm not sure that anyone takes Ebbinghaus's forgetting curve as the gospel truth explanation of forgetting - it's more to illustrate the fact that this topic has been studied and we can learn from it for teaching. And his work is also misunderstood for all sorts of agendas.

In a contemporary classroom context, what are the types of information or topics where the work on retrieval is misapplied for disconnected rote learning? In other words, what have you observed to be the fertile ground for lethal mutations?

An enlightening piece, thanks. It resonates with the work I've been doing on the topic of spelling instruction stemming from my PhD: the notion of building multi-faceted representations of words through cumulative learning of words via an instructional routine that supports retrieval in connected & meaningful ways: Focus 1 (Ph) + Focus 2 (Or) + Focus 3 (M) + Focus 4 (cross-mapping PhOrM).