What Makes Spaced Practice So Powerful?

New research challenges the idea that spacing works through rest

I’ve been thinking and reading a lot about spacing over the last few months as I’ve been writing a new paper on the topic with John Dunlosky and Paul Kirschner. In our conversations, John said something to me that was so completely obvious but also something I hadn’t properly considered before: spacing is not a strategy, it’s a schedule.

This simple fact made me realise why so much spacing research feels disconnected from classroom reality: we've been studying spacing as if it's a pedagogical choice rather than a logistical one.

And it also made me realise that understanding how spacing works cognitively becomes even more important when you view it as a scheduling decision. If teachers need to make timetabling choices about spacing, they ideally need to know what's actually happening during those intervals. So it was with considerable excitement that I discovered a new paper which answers this very question.

How Does Spacing Work?

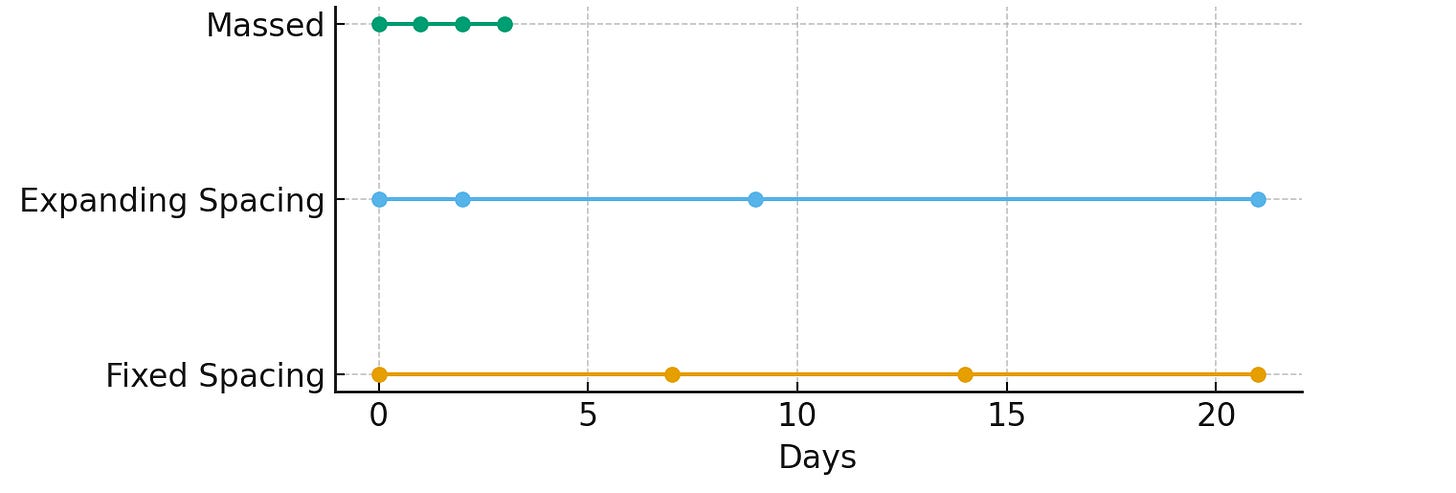

The spacing effect is one of the most reliable findings in learning research, but understanding precisely why it works has proved more elusive. Consider this typical study: Petersen-Brown and colleagues (2019) asked primary school students to learn mathematics vocabulary across multiple practice sessions. Some students completed all their practice sessions clustered together over just a few days (massed practice), whilst others spread identical sessions across several weeks using either consistent seven-day gaps (fixed spacing) or progressively longer intervals starting with two days, then seven, then twelve (expanding spacing).

When tested a week after their final session, both spaced groups significantly outperformed the massed group in recalling the mathematical terms, but with no meaningful difference between fixed and expanding schedules.

So we know spacing consistently beats massing but why no difference between fixed and expanding schedules here? And does that mean we should be labouring about the timing ridgeline effect of spacing? In other words, are we overcomplicating a fundamentally simple principle by searching for nuanced schedule effects that may not exist or matter in practice?

All this underlines to me that the difference between knowing that spacing works and understanding how it works are different questions entirely. And if we're going to make intelligent scheduling decisions, we need to understand the mechanisms. But which mechanisms actually drive the spacing effect?

The Competing Theories

In terms of scheduling, two main theories have emerged, each with very different implications for how we should schedule learning.

The Rest and Recovery Theory: For years, researchers believed spacing worked because intensive learning depletes our working memory resources, like a cognitive fuel tank that empties and needs refilling. The gaps in spaced practice supposedly give our brains time to recover before the next learning session. This made intuitive sense: we all know the feeling of mental fatigue after intense study.

The Mental Rehearsal Theory: But there's another possibility: during those gaps, our brains don't switch off, they keep working. We continue processing the material unconsciously, strengthening memory traces even when we're not actively studying. Think of it as the cognitive equivalent of muscles developing between practice sessions.

These theories suggest very different scheduling strategies. If spacing works through recovery, then longer gaps might be better for complex material. However, if it works through rehearsal, then the optimal gap depends on how long the brain needs to process specific content.

Testing the Theories

To understand their approach, we need to grasp the concept of 'element interactivity'; essentially, how many pieces of information must be processed simultaneously in working memory. Low element interactivity materials can be learned piece by piece independently. High element interactivity materials require holding multiple pieces of information in mind at once, creating greater cognitive load.

In this new paper, (which is open access) Researchers Kaiyin Chan, Ouhao Chen, and Fred Paas decided to test these competing theories directly. They had students learn calculus differentiation rules under two conditions: massed (all at once) or spaced (with breaks). But here's the clever bit, they measured working memory depletion after learning to see which theory was correct.

They ran two experiments with different types of mathematical content. In the first experiment, students memorised simple differentiation rules (like how to differentiate x²). These were considered low complexity because each rule could be learned independently. In the second experiment, students tackled complex differentiation problems that required applying multiple rules simultaneously, high complexity material that should theoretically exhaust working memory.

The researchers' predictions were clear: if the rest and recovery theory was correct, they should see working memory depletion in the massed groups, especially with complex material. If mental rehearsal was the mechanism, they might see spacing benefits without measurable depletion.

The (somewhat) Surprising Results

The results were interesting. In both experiments, spaced practice won. As you’d expect, students performed better on tests when learning was distributed over time. But working memory wasn't significantly depleted in either the massed or spaced groups, regardless of material complexity. This finding challenges the plausible "rest and recovery" explanation. If spacing doesn't work by allowing depleted cognitive resources to replenish, then what's actually happening during those gaps?

Basically the evidence pointed to mental rehearsal. Even when students weren't consciously trying to rehearse, their brains appeared to keep processing the material during breaks. Interestingly, this happened even with the more complex mathematical problems, suggesting that once students had some foundational knowledge, they could mentally rehearse quite sophisticated material.

The researchers proposed that prior knowledge changes everything: students who'd mastered basic rules in the first experiment could use that knowledge to mentally process complex problems in the second experiment, effectively reducing the cognitive complexity through the application of learned schemas.

What This Means for Scheduling Learning

This potentially changes how we should think about spacing schedules. If the brain continues working during gaps, then the length and timing of those gaps becomes crucial, not for recovery, but for optimal processing time. Consider the practical implications. When scheduling spaced practice, we're not just preventing cognitive overload, we're providing processing time. This suggests several key principles:

Prior knowledge matters for spacing design. Students with more background knowledge may benefit from different spacing patterns because they can mentally rehearse more effectively. A novice might need shorter, more frequent spacing to avoid cognitive overload, while an expert might benefit from longer gaps that allow deeper consolidation.

The content of gaps may be crucial. If mental rehearsal is happening unconsciously, then what students do between learning sessions could either support or interfere with this process. A busy, cognitively demanding activity might disrupt ongoing rehearsal, while a quiet break might enhance it.

Material complexity isn't fixed. What counts as "complex" depends on the learner's existing knowledge. This means spacing schedules should adapt as students develop expertise in a domain.

The Limitations (And Why They Matter)

But before we revolutionise our timetables though, we need to acknowledge this study's limitations. The working memory test might not have been sensitive enough to detect subtle resource depletion. The researchers used the same cognitive test across both experiments, which could have created practice effects that masked true depletion.

Perhaps more importantly, mental rehearsal wasn't directly measured, it's inferred from the absence of other explanations. We don't actually know what students' minds were doing during those gaps. Some might have been rehearsing mathematical rules, others might have been thinking about lunch.

The study also used the same students across both experiments, which means the "complex" material in Experiment 2 might not have been truly complex for students who'd just learned the foundational rules. This limits our ability to generalise about how spacing works with genuinely novel, difficult content.

These limitations don't invalidate the findings, but they do suggest we should be cautious about drawing sweeping conclusions. The research opens important questions rather than settling them definitively.

What Should Teachers Do?

Despite these limitations, the research suggests we should schedule spacing with mental rehearsal in mind. This means considering what students might be unconsciously processing during gaps, and designing those intervals to support rather than interfere with ongoing cognitive work.

For familiar material: Space practice to allow consolidation time. Even content students think they "know" may benefit from gaps that allow deeper processing and integration with existing knowledge.

For complex new material: Consider whether students have enough prior knowledge to rehearse effectively. If they're complete novices, shorter initial gaps might be better until they develop some foundational schemas.

Design the gaps thoughtfully: Think about what happens between sessions, not just during them. A gap filled with related but low-demand activities (like reviewing notes quietly) might be more beneficial than a gap filled with completely unrelated cognitive tasks.

Adapt as knowledge grows: Spacing schedules shouldn't be static. As students develop expertise, they may be able to benefit from longer gaps that allow more sophisticated mental rehearsal.

Most importantly, remember that spacing is indeed a scheduling decision, but it's an intelligent one that should be informed by our growing understanding of the cognitive processes that unfold between learning sessions. We're not just distributing practice in time; we're creating conditions for the mind to do its hidden work of making memories stick.

I don't have a great understanding of the details of research behind spacing but the two models you describe are different from my mental model. My mental model is that storage strength + retrieval strength predict learning in an isolated context where we want to see how to help students remember a specific piece of knowledge. When retrieval strength is low, retrieving contributes more to storage strength.

The intuition here is that when retrieval strength is low, it takes more effort to remember something and that additional effort contributes to storage strength and long-term memory.

From my perspective, there are two big confounding variables. First is retrieval success. Unsuccessful retrieval doesn't do much for long-term memory, so you want to space learning to reduce retrieval strength but make sure it doesn't fall so far that retrieval is unsuccessful. And second is connections to other knowledge in long-term memory. If two ideas are connected, retrieval can reinforce both ideas, and learning is much easier than if ideas aren't explicitly connected for students. Those can explain many of the weird results I've seen concerning spacing.

I like this model because it gives me practical strategies for class. I want to space practice, but if student's aren't retrieving successfully I need to reteach and reduce the interval. If I see students need a ton of practice and are making slow progress I emphasize connecting ideas and not retrieving skills in isolation.

Do you think the two models you describe add value over and above the storage/retrieval model?

"Spacing is not a strategy, it’s a schedule." - However, rehearsal and retrieval can both be strategies. I think it's a combination of the spacing and the strategy that matter. And, it is not the same for everyone - so many variables - student working memory, student prior knowledge, student age, student attention span...