The Research Brief: What's New in Learning Science - November 2025

New research on reading instruction, retrieval practice, feedback, fluency, and the limits of social-emotional learning.

A new Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (GEEAP) report leads this month’s review, showing that explicit, structured teaching of six core skills (language, phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, comprehension, and writing) is the most effective way to teach reading worldwide. The literacy crisis, it argues, is one of instruction, not access.

Other highlights: retrieval practice only beats other active methods when feedback is given; universal SEL lessons show no mental health impact; and fluency grows faster with challenging texts than with levelled readers. Handwriting outperforms typing for early literacy, emotional intelligence predicts growth only in narrative reading, and strong readers succeed by strategically rereading rather than slowing down.

This comprehensive report addresses the global literacy crisis, noting that 70% of ten year old children in low and middle income countries (LMICs) cannot read and understand a simple text. It argues this is primarily a crisis of instruction, caused by a failure to use teaching methods proven by research. The report synthesises over 120 studies from LMICs and confirms that the core principles of effective reading instruction, often called the “Science of Reading”, are universal. It identifies six essential, interconnected skills that must be taught: oral language, phonological awareness, systematic phonics, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and writing. The authors conclude that these skills must be taught explicitly (modelled directly by the teacher), systematically (in a logical, planned sequence), and comprehensively (all six skills must be addressed) .

For educators, this report provides strong validation for a structured, skills based literacy programme. It explicitly contrasts this approach with whole language or discovery methods , stating that children do not learn to read “naturally” in the same way they learn to speak ; reading must be directly and systematically taught. The key implication is that daily classroom time should be purposefully allocated to all six skills. This includes direct instruction in manipulating spoken sounds (phonological awareness) and matching letters to sounds (phonics), rather than assuming children will absorb these skills simply by being exposed to books. It also underscores the critical need to build oral vocabulary , as a child cannot comprehend a written word they would not understand if it were spoken to them.

The study followed 2,425 children (aged 8–9) in 62 English primary schools assigned to either teach Passport or carry on as normal. Teachers delivered 18 weekly lessons in five modules (emotions; relationships/helping; difficult situations; fairness/justice; change/loss). The researchers preregistered the trial, masked the lead analyst, and used pupil self-reports on mood (primary outcome) and secondary measures (emotion regulation, well-being, loneliness, bullying, peer support). The main result was null: the intention-to-treat effect on internalising symptoms was essentially zero (d ≈ −0.04; CIs straddled zero). Secondary outcomes were similarly null.

For teachers and leaders, the takeaway is that a short, generic, whole-class SEL course layered onto normal timetables is unlikely to shift pupils’ internal feelings (anxiety/low mood) in upper primary. The authors’ most plausible explanation is differentiation failure: the programme was not meaningfully different from the SEL-type content and routines many schools already provide, so it added little. In practice, schools should be wary of buying “off-the-shelf” universal SEL packages expecting measurable mental-health gains; effort may be better spent strengthening your existing provision, targeting support, and improving classroom relationships and routines school-wide.

We’ve long known that retrieval practice is a powerful learning strategy, but many of the studies mostly compare it to passive rereading. This new systematic and meta analytic review asked a more practical question: how does retrieval practice stack up against other good strategies that teachers use, such as concept mapping, note-taking, or generating self explanations?.

The review synthesised 44 studies and 142 direct comparisons and found that retrieval practice does hold a small, significant advantage overall. However, this tiny average effect hides the real story. The benefit was strongest for free recall tests (versus cued recall) and for learning complex materials. Most strikingly, retrieval’s advantage was only significant when compared against concept mapping and group discussions, and it produced indistinguishable results when compared to most other active tasks.

The most critical, actionable finding is about feedback: retrieval practice was only superior to elaboration when feedback was provided. When feedback was absent, elaborative tasks were actually more beneficial. This strongly suggests that teachers must not simply swap active tasks like concept mapping for quizzes; instead, they must ensure any retrieval practice activity is always followed by an opportunity for students to check their answers and correct errors. The findings support a combined approach: using elaborative tasks to build initial understanding and retrieval practice (with feedback) to consolidate it for the long term.

This OECD international survey describes what teaching looks like in practice in 2024: how teachers spend their time, the support and development they receive, their classroom climate, use of evidence informed practices, and their views on workload, well being, and career intentions. The headline story is a profession that remains committed to pupils but is stretched by administrative load, mixed access to high quality professional development, and uneven instructional support and autonomy. It also surfaces variation between systems that points to policy and school level levers that are within reach.

The survey also shows that classroom time is often eroded by behavioural issues and paperwork, yet schools with stronger collaboration, feedback, and clear routines report better instructional conditions and teacher satisfaction. It suggests practical moves such as reclaiming instructional time from low value tasks, targeting development to subject specific needs, strengthening collegial observation and feedback, and aligning behavioural routines to protect learning time. It also gives school leaders comparative benchmarks to judge whether their teachers’ experience is typical or signals a local problem that can be solved.

Giving students a “learning goal” before instruction led to better conceptual knowledge. They increase cognitive load , forcing a deeper engagement that shallow problem solving goals allow students to bypass using minimal effort strategies.

This study asked secondary students to tackle a statistics problem on consistency of footballers’ goal scoring before a short explicit lesson on mean absolute deviation, and experimentally varied two things about the task brief: whether the goal was to learn about the concept or to solve the problem, and whether the goal was specified or left open. Specified goals led pupils to propose more relevant solution ideas, and relevance correlated with post lesson conceptual knowledge; learning goals outperformed problem solving goals on conceptual knowledge even though they did not increase the number of ideas generated. The Johnson Neyman plot shows that students with mid to high mastery goal orientation gained most from learning goals, indicating a motivational pathway alongside cognitive mechanisms (see Fig. 3). The task wordings for all four conditions are shown in Table 1, and the condition level outcomes in Tables 2 and 3.

This meta-analysis synthesised evidence from 51 studies involving 7,673 participants across age groups to examine how different interventions reduce mathematics anxiety. It compared three approaches: (1) maths skills-oriented interventions (focused on instruction and practice), (2) anxiety-oriented interventions (such as cognitive reappraisal or relaxation), and (3) combined interventions integrating both.

The findings found that combined approaches yielded the largest reduction in maths anxiety (Hedges’ g = −1.09), followed by anxiety-only (g = −0.71) and skills-only (g = −0.37) methods. However, for actual maths performance gains, only the skills-oriented interventions had significant effects. The authors interpret this as evidence that weak mathematical ability may underlie anxiety, and that reducing anxiety alone may not immediately improve achievement.Forget about breathing exercises or mindfulness; confidence follows accuracy, not the other way round.

The study tested first graders and sixth graders on three hundred single digit additions each, classifying problems as ties, non ties, zero and one problems, and analysed response times with mixed effects models. First graders showed steep problem size effects for both ties and non ties, indicating counting; by sixth grade, ties showed a flat profile and zero problems were flat, but small non tie problems still increased linearly with size, and one problems showed a curved pattern rather than flat, pointing to mixed processes. Figures on pages 8 to 12 visualise these trends: Figure 1 shows the general rise in times with sum for non ties and the near flat line for small ties in Grade 6; Figures 2 to 4 plot the linear slopes for very small and medium small non ties and the flattening of large ties by Grade 6; Figure 5 shows flat zero problems and the quadratic shape for one problems.

For teachers, this matters because it suggests that fluent fact retrieval is achieved early for easy patterns like ties and adding zero, but not uniformly for all small additions. Classroom fluency routines should therefore distinguish between categories: keep retrieval practice for ties and tens complements, but continue structured strategy teaching plus retrieval for small non ties, because interference among similar facts seems to drive the residual slowing.

This research dismantles the assumption that slower reading automatically signals effective comprehension monitoring. Using sophisticated eye-tracking methodology, Tibken and Tiffin-Richards reveal that what matters is not whether readers slow down when encountering contradictions, but whether they deliberately return to reanalyse problematic passages. The study found that rereading time and revisit probability at the target word level strongly predicted inconsistency detection in complex expository texts, whilst first-pass reading disruptions offered little predictive value. This challenges models suggesting passive validation suffices for expository text comprehension, instead supporting theories like Richter and Maier’s Two-Step Model of Validation, which posits that difficult texts require active metacognitive effort beyond automatic processing. The findings suggest that when content is conceptually demanding and inconsistencies are subtle, readers must engage strategic regulatory behaviours such as verification, rechecking, and deliberate rereading of the source of confusion, rather than relying on the dysfluency they experience during initial reading.

This study taught 50 prereaders nine unfamiliar letters (from Georgian/Armenian) and 16 two-syllable “words” built from those letters. Children were randomly assigned to one of four training methods: hand-copying, tracing, typing with multiple fonts, or typing with a single font. After short training blocks across two days, they were tested on naming, writing, and visually identifying the letters and words. The headline result is consistent and striking: the two handwriting groups outperformed both typing groups on nearly every meaningful outcome, naming letters and words, writing them from dictation, and recognising trained words, while simple visual letter identification was near ceiling for all. The authors argue this pattern supports the “graphomotor” hypothesis: the coordinated eye-hand movements and strokes involved in forming letters help bind visual forms to sounds and sequences.

Across 4,813 students in 41 studies, Rogers Kaliisa and colleagues found no significant performance difference between students receiving AI-generated feedback and those receiving human feedback (Hedge’s g ≈ 0.25, CI [−0.11, 0.60]). AI feedback was often faster and more consistent, while human feedback retained advantages in empathy, nuance, and contextual understanding. Students generally perceived both forms as comparable, though some valued the personal touch of human responses more.

This study examines trends in self-reported cognitive disability using a decade of national surveillance data, deliberately excluding individuals with depression to isolate non-psychiatric cognitive impairment. The findings challenge conventional assumptions about cognitive decline being primarily an older adult concern. The near-doubling of cognitive disability prevalence in 18-39 year olds (from 5.1% to 9.7%) stands in stark contrast to the slight decline in adults over 70. This inversion of the expected age gradient suggests that younger generations face distinct cognitive stressors that older cohorts may have avoided or that improvements in cardiovascular disease management have protected older adults’ cognitive health.

This study piloted a fluency protocol called ‘Read Like Us’ with 100 fourth grade students across 10 schools. The intervention involved students reading each text five times using different scaffolds (teacher modelling, echo reading, choral reading, partner reading, then a performance read), working through 50 diverse texts over 50 sessions. Critically, 90% of these texts were at or above grade level, deliberately challenging students rather than matching them to independent reading levels. Students showed substantial improvements in reading automaticity and accuracy, with effect sizes ranging from 0.8 to 1.8 across fluency measures, outperforming a comparison group who used traditional levelled intervention materials.

This study looked at how the meanings of words change over time and how that connects to when we first learn those words. Using dictionary data and computer models of language, the researchers found that words learned early in life tend to stay more stable in meaning, though they often gain extra meanings as people use them in new ways. Words learned later are more likely to shift in meaning and show more short-term changes. In other words, the core vocabulary we learn as children stays steady but grows richer, while newer words are more flexible and change faster.

The authors ask how children’s age of acquisition relates to how word meanings change through history. Using Oxford English Dictionary example sentences mapped with BERT and aligned with the Corpus of Historical American English from 1850 to 2020, they estimate, per decade, how often a word appears with each dictionary sense. From these sense distributions they compute three complementary indicators: wiggliness (short term fluctuation), displacement (long term shift), and diversification (growth in polysemy). They then model links with age of acquisition while accounting for frequency and other covariates, and compare directional patterns with Bayesian networks.

This study followed 588 children who entered competitive lotteries for places at 24 public Montessori schools across the United States, comparing those offered a seat with those who were not, and tracking outcomes from preschool entry to the end of kindergarten. While there were no notable impacts at the end of the three and four year old years, Montessori offer produced statistically significant end of kindergarten gains in early reading, executive function, forward digit span and theory of mind, with intention to treat effect sizes a little above a fifth of a standard deviation and larger complier effects; the authors note this is large for field based education trials.

This longitudinal study tracked 689 Chinese students from Grade 3 to Grade 5, examining whether emotional intelligence (the ability to perceive, regulate, and use emotions) predicts reading comprehension development. Using latent growth curve modelling, the researchers found that emotional intelligence predicted where students started in their reading ability for both story-based and informational texts, but only predicted how quickly students improved over time when reading narratives. The effect was specific: emotional intelligence matters more for understanding stories with characters, feelings, and social dynamics than for digesting factual information from non-narrative texts like textbooks or encyclopaedia entries.

This study investigated whether artificial intelligence could infer human personality from text as well as people can. Over a thousand participants wrote 1,000 word autobiographies and completed 30 validated psychological questionnaires measuring personality, values, coping styles, and emotional tendencies. GPT 4 was then asked to predict how each participant would answer these questionnaires based solely on their writing, without any training data or examples. The AI’s predictions correlated with actual responses at r = 0.35 (adjusted for measurement error: r = 0.41), matching the accuracy research typically finds among real world friends. Meanwhile, 1,374 human judges reading the same texts achieved significantly lower accuracy (r = 0.20, adjusted r = 0.23). Across scales, the AI and humans struggled with similar constructs, suggesting some psychological traits are inherently harder to infer from text regardless of whether the judge is silicon or carbon based.

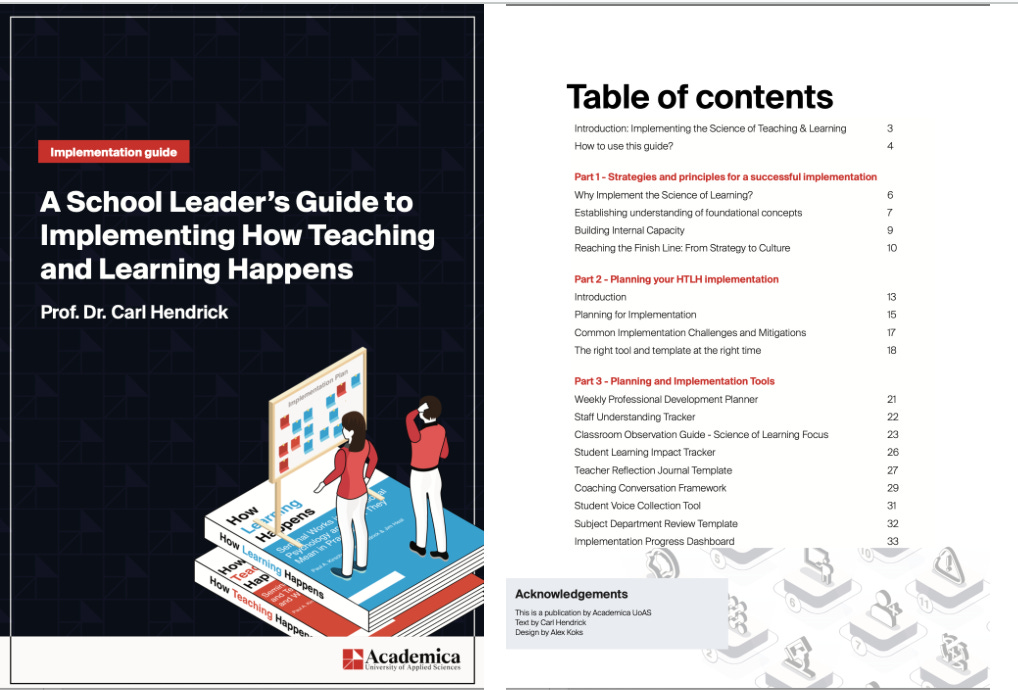

I’ve written a free science of learning implementation guide for school leaders as part of the How Teaching and Learning Happens e-learning course. Download here.

Some recent podcast appearances:

Always enjoy reading these.

Some related questions, if I may, regarding the retrieval study:

1. I was surprised to see you write that note-taking is a good strategy for studying. I'm not an expert, but most of the research I've read puts this as a quite weak form of study (which makes sense: it's passive)

2. Re "only superior when feedback was provided": This is essentially flashcards, right? As in, with a typical exam/quiz the student will either not find out the answers, or have to wait considerable time. Of course with flashcards, it is provided instantly. If they answer incorrectly, it simply remains in the session's deck.

3. Aren't methods such as "group discussions" or "self-explanations" etc also forms of retrieval? This is something I've had a few discussions with people over and I've never really followed how such methods can not be based upon retrieving from memory.

Thank you.

It's telling that the GEEAP paper talks a lot about cost effectiveness, and not about devoting more resources to ameliorate this supposed international crisis.

Also, with their recommendations on micromanaging reading instruction, they seem to completely ignore a century-old body of eye-movement research:

"Research on eye movement in reading has shown that reading comprehension is optimal if the reading materials are natural and close to the reader’s cognitive and life experiences. Moreover, readers should be taught to use the information from different textual, nonverbal visual features, and multiple representations and modes to assist comprehension. Comprehension is also optimal if reading instruction is embedded in a wide cross-disciplinary curriculum through which students build up general and specific background knowledge for reading and learning. In the continuous conversations about reading and reading instruction, let’s not forget these very principle understandings about reading and how students read most successfully based on the body of century-old eye movement research."

Hung, Y. - N. (2021). The science of reading: The eyes cannot lie. International journal of education and literacy studies, 9(4), p. 26-31.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1328890.pdf

https://www.emmaforum.org/Biblio

Also, maybe postmortem fish can read human social situations:

https://www.mathematik.uni-rostock.de/storages/uni-rostock/Alle_MNF/Mathematik/Struktur/Lehrstuehle/Analysis-Differentialgleichungen/salmon-fMRI.pdf