The Lethal Mutation of Retrieval Practice

Five ways to get retrieval practice wrong and reflections on a new study which shows that when material is complex, retrieval can stop being a desirable difficulty and start being an undesirable one.

For decades, the testing effect has been one of the most reliable findings in the science of learning. It is now the darling of the new evidence-informed movement, the miracle treatment that promises deeper learning simply by asking students to bring information to mind. And for novices tackling well-defined material, it works. Repeatedly.

But like most ideas in education that reach canonical status, the story is incomplete. Even tried and tested methods can be applied in a way that is not supported by the evidence. A new study complicates the established narrative and forces us to examine a question that rarely gets asked: Does retrieval practice work with all types of knowledge? what about when students are dealing with genuinely complex material that has many interacting elements? The answer, it turns out, is not as straightforward as many would like to believe.

The Study: Does Retrieval Practice Work With Complex Material?

In this new study, Redifer and colleagues (2025) gave 213 undergraduates something rarely seen in testing effect research: genuinely difficult material. Not word pairs. Not a three paragraph passage. A published psychology journal article, 2500 words, Flesch Kincaid reading level 13.5. The kind of thing students actually encounter in university courses.

After reading, participants either reread the article or engaged in retrieval practice: free recall, practice quizzes, generating their own test questions. One week later, everyone took a final test. The result: nothing. No difference between conditions. Retrieval practice produced no advantage whatsoever.

But here’s the thing: cognitive load fully mediated the effect. Students in the retrieval conditions reported higher mental effort, and that effort predicted worse performance. The retrieval practice was not strengthening memory. It was overwhelming it.

Bayesian analysis suggested the null result was approximately seven times more likely than a meaningful group difference. This was not a case of insufficient power or ambiguous findings. The testing effect, under these conditions, simply did not appear.

This study confirms a suspicion I have had for a while, which is that because it’s not fully understood, retrieval practice is rapidly becoming a lethal mutation. In simple terms, this means the distortion of a practice with good evidence to support it in the laboratory but then gets misapplied in the field and becomes a pale imitation of its former self.

A lethal mutation is an idea or a practice that is prompted by sound scientific evidence, but is implemented in a way that reduces, or even completely negates, its effectiveness.

Over the last few years, I’ve been noticing more and more examples of retrieval being used in ways that extend well beyond what the evidence supports. One-off quizzes at the start of every lesson which are forgotten within a week. Poorly designed flashcard apps pushed as the solution to retention problems. “Retrieval grids” and “brain dumps” deployed as all-purpose learning tools, regardless of what students are learning or how far along they are in understanding it. And worst of all, kids retrieving random facts from an incoherent curriculum.

The enthusiasm is understandable. When a finding replicates as reliably as the testing effect, it’s tempting to generalise. If quizzing works for vocabulary, why not for literary analysis? If it works for historical dates, why not for historical causation? If it works after students have studied something, why not as a way of studying it in the first place?

Well this kind of overfitting is precisely the problem and this new study crystallises something I think is widely misunderstood, which is that retrieval practice is a consolidation strategy, not a comprehension strategy. It works when learners already have something in memory worth retrieving. It strengthens existing traces; it does not build them. When students are still grappling with understanding, when they are still constructing the schema that will eventually be worth consolidating, asking them to retrieve is asking them to lift weights they haven’t yet built the muscles for.

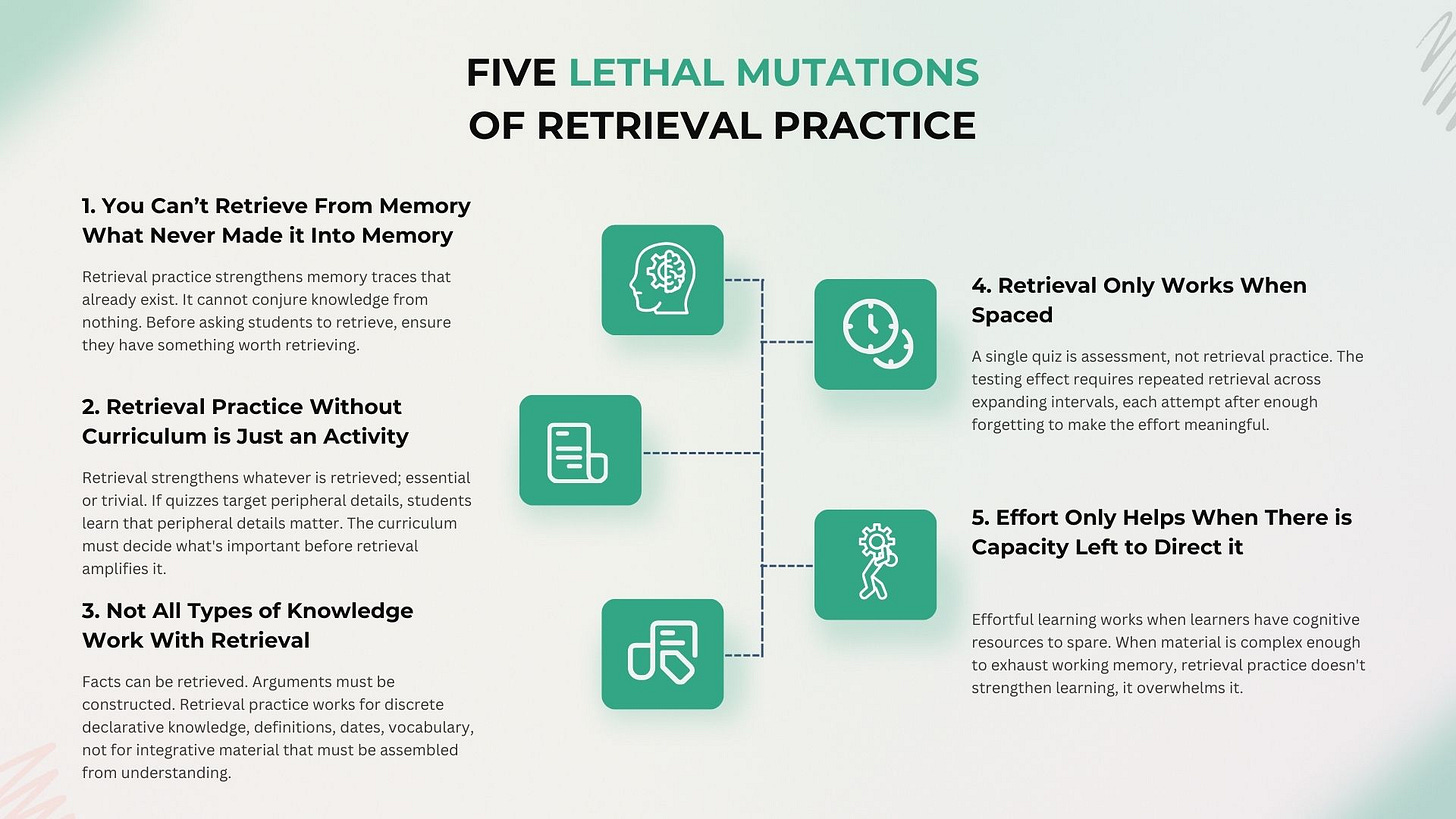

So in an effort to inoculate against the mutation and try to highlight ways of using this powerful strategy more effectively, here are 5 principles to avoid using retrieval practice in ways not supported by the evidence.

1. You Can’t Retrieve From Memory What Never Made it Into Memory

Retrieval practice works by strengthening memory traces that already exist. The act of pulling information out of long-term memory; of searching, effortfully reconstructing, generating an answer from partial cues, consolidates and stabilises what has been learned. But this mechanism presupposes that something has been learned. There must be a memory trace to strengthen. Retrieval practice is not alchemy. It cannot conjure knowledge from nothing.

This seems obvious when stated plainly. Yet in practice, the distinction is often routinely ignored. Too often, I see students asked to retrieve material they’ve barely encoded. They’ve read something once, understood perhaps 60% of it, and are now being told that the best thing they can do is close the book and try to recall what they’ve learned.

What follows from this is not retrieving knowledge. It’s floundering. The student searches memory and finds fragments; half-remembered phrases, vague impressions, isolated facts unmoored from meaning. They write something down, or they don’t. Either way, the exercise has not strengthened understanding. It has merely exposed its absence.

There is a version of retrieval practice that strengthens memory, and a version that overwhelms it. The difference lies in what the learner brings to the task. When knowledge is secure, when the student could, with time, actually produce the answer, retrieval deepens the hold. The effort is desirable because it lands on something solid. But when knowledge is fragile, partial, or absent altogether, the same effort becomes noise. The student isn’t retrieving; they’re guessing. And guessing, however effortful, does not produce the testing effect.

The practical implication is straightforward but frequently violated: retrieval practice belongs after initial learning, not during it. It is a tool for consolidation, not a substitute for instruction. Before you ask students to retrieve, you must first ensure they have something worth retrieving, and that means teaching, explaining, checking for understanding, and allowing time for encoding. Only then does the testing effect have something to work with. I fully agree with Robert Bjork that testing is a learning event but retrieval requires something to retrieve.

2. Retrieval Practice Without Curriculum is Just an Activity

Retrieval practice strengthens whatever is retrieved. It does not discriminate between the essential and the trivial. This is a feature when retrieval practice is well designed but it becomes a serious problem when it is not.

For example, a quiz can ask students to retrieve the dates of Henry VIII’s marriages or the names of characters in a novel or the definitions of technical terms. Students dutifully retrieve this information, and their memory for it is duly strengthened. But if that information is peripheral to the actual learning goals, if it crowds out attention to the conceptual architecture that students actually need to understand, then retrieval practice has succeeded at the wrong task. The strategy “worked”, it just worked on the wrong material. The operation was a success but the patient died.

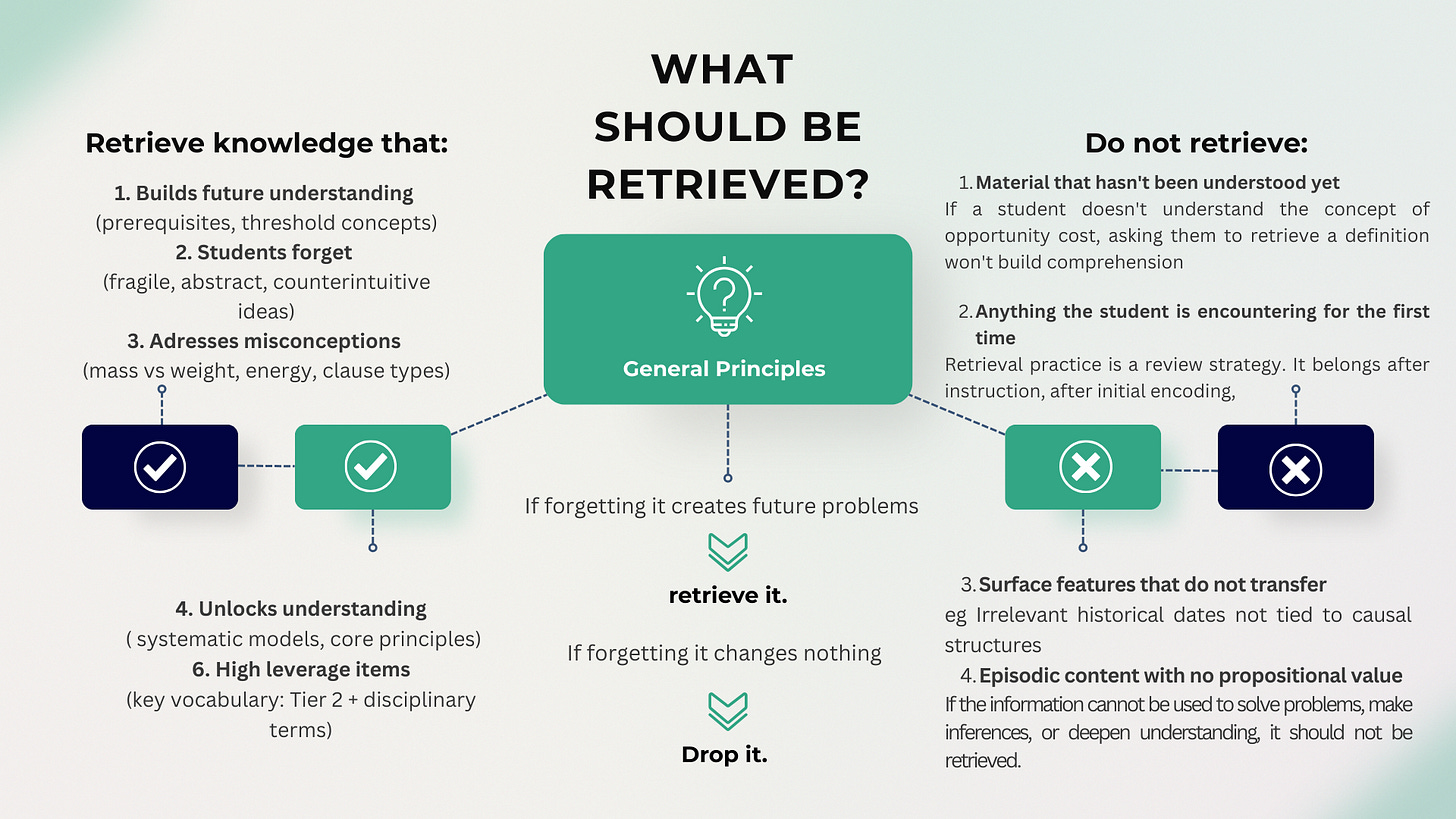

This is where curriculum planning becomes non negotiable. Before we can design effective retrieval practice, we must know what is worth retrieving. What are the threshold concepts that, once grasped, transform how students see the entire domain? What are the hinge points where understanding either consolidates or collapses? What are the ideas that carry the most weight, that unlock the most doors, that students will need again and again as they progress?

When the curriculum is not sharply planned, students can spend time recalling trivia, peripheral details, or whatever happened to stick rather than the conceptual load bearing ideas that actually drive understanding. Retrieving irrelevant information gives the illusion of learning because the act feels effortful and productive, but it does nothing to strengthen the mental architecture that future knowledge depends on.

Worse still, the risk is that retrieval practice, poorly targeted, actively distorts students’ understanding of what matters. If quizzes consistently ask about surface details, students learn that surface details are what count. They allocate their attention accordingly. The assessment, even a low stakes formative one, signals importance. If we signal that trivia matters, students will optimise for trivia. They will walk into examinations with strong memories for peripheral information and weak memories for the ideas that actually structure the domain. Making a quiz is easy. Knowing what should be on the quiz is what’s hard.

The curriculum must decide what the signal is before retrieval amplifies it.

3. Not All Types of Knowledge Works With Retrieval

The testing effect was established using materials that lend themselves to retrieval: word pairs, definitions, isolated facts. These are discrete. They have edges. You recall them or you don’t. But not all knowledge has this structure. An interpretation of a novel, an analysis of historical causation, a synthesis of competing theoretical perspectives; these are not items stored in memory awaiting collection. They must be constructed in the moment, assembled from understanding rather than retrieved from storage.

What makes someone effective at discussing complex ideas is not that they have memorised a list of interpretations but that they can mobilise a rich store of knowledge about that topic and the emerging context in a flexible way.

When we ask students to engage in retrieval practice with integrative material, we are asking them to do something subtly different from what retrieval practice was designed for. The student who “retrieves” an argument is not strengthening a memory trace; they are rebuilding an edifice each time, and the cognitive demands of that rebuilding may overwhelm any consolidation benefit. The Redifer study used a journal article, a text that required integration, inference, and synthesis. That’s not incidental to the null result. It’s central to it.

The practical implication: before designing retrieval practice, ask what kind of knowledge you’re targeting. If it’s discrete and declarative, retrieval works. If it’s relational or integrative, you may need a different tool, or you need to break the knowledge into retrievable components first.

4. Retrieval Only Works When Spaced

The testing effect is not produced by a single act of retrieval. It is produced by repeated retrieval, spaced over time, each attempt carried out after enough forgetting has occurred to make the effort meaningful. Karpicke and Roediger (2008) demonstrated that repeated retrieval dramatically outperforms single retrieval, and that the benefits compound with each successive attempt.

Consider what this means in practice. A teacher finishes a unit on cellular respiration. Students take a quiz. They perform reasonably well. The class moves on to photosynthesis, then to ecology, then to genetics. Cellular respiration is never revisited. By the end of the year, it might as well never have been taught.

That single quiz was not retrieval practice. It was assessment. It measured what students knew at that moment; it did not change what they would know later. For retrieval to strengthen memory durably, students must retrieve again, and again, across expanding intervals. Each retrieval must occur after some forgetting, so that the act is effortful. Without this return, there is no testing effect. There is only the illusion of one.

The mutation is architectural: curricula designed as a sequence of discrete topics, each assessed once and then abandoned. The fix is also architectural: cumulative retrieval built into the bones of a course, with past material returning systematically rather than disappearing into the rear-view mirror.

5. Effort Only Works When There is Capacity Left to Direct it

The desirable difficulties framework has become one of the most influential ideas in contemporary education. The logic is compelling: learning that feels easy is often shallow, while learning that requires effort tends to stick. Retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, variation: these strategies work precisely because they make learning harder in productive ways. The effort is the point.

But effort is not a free resource. It draws on a limited pool of cognitive capacity, and that pool can be emptied. When learners are grappling with complex material, when the content itself demands everything they have, there may be nothing left for the additional effort that retrieval practice requires. The Redifer study caught this in action: students who engaged in retrieval practice reported higher cognitive load, and that load predicted worse performance. The effort was being made, but it was effort without direction, exertion without purchase, wheels spinning on ice.

The metaphor I find most useful is physical. Imagine asking someone to carry a heavy load up a flight of stairs. If they are fresh and the load is manageable, the exercise strengthens them. Now imagine asking them to carry that same load after they have already climbed ten flights with an even heavier burden. The additional effort does not build strength. It causes collapse. The exercise is identical, but the context has changed everything.

Cognitive effort works the same way. The desirable difficulty of retrieval practice assumes that learners have cognitive resources available to struggle within a range that is not overwhelming. When those resources are already depleted by the demands of the material itself, the struggle stops being productive. The difficulty stops being desirable. What remains is just difficulty: effortful, exhausting, and educationally inert.

This is why sequencing matters so much. Retrieval practice should be introduced when learners have built enough understanding that retrieval is feasible, when the cognitive load of comprehension has subsided enough to leave room for the cognitive load of retrieval. Getting this sequence wrong does not merely reduce the benefit of retrieval practice. It can eliminate it entirely.

Summary

So retrieval practice works. But it has a failure mode. The testing effect remains one of the most robust findings in the science of learning, replicated across hundreds of studies and verified by multiple meta-analyses and nothing in the Redifer study, or in this article, should be taken as grounds for abandoning the strategy.

But retrieval practice has boundary conditions, and I feel that in the science of learning community, we have been slow to acknowledge them and what has emerged is a set of practices that are not an effective use of student time. When cognitive load is already high, when material is complex and integrative, when learners are still constructing the schema they will eventually consolidate, retrieval practice may not help. The effort it demands may exceed the cognitive resources available, converting a desirable difficulty into an undesirable one. The strategy doesn’t fail because it’s ineffective. It fails because it’s being applied outside the conditions that make it effective.

The Redifer study is one study. It used one type of material with one population. But it crystallises something the field has been circling for years: the testing effect was established with simple materials, and simple materials remain where it works best. The further we move from word pairs and paragraph-length passages toward genuine academic complexity, toward the kinds of reading students actually encounter, the less we should assume the effect will transfer intact.

The solution is not to retreat from retrieval practice. The solution is to deploy it with more precision. This means attending to sequence: comprehension first, consolidation second. It means attending to curriculum: knowing what is worth retrieving before asking students to retrieve it. Crucially, it also means attending to knowledge type: recognising that discrete facts behave differently from integrative arguments. And finally it means attending to spacing: building return into the architecture of a course rather than treating each topic as a closed episode.

Retrieval practice is a powerful tool. But like all powerful tools, it requires careful judgement. The enthusiasm of the evidence-informed movement has spread the strategy widely. The next task is to ensure it’s being used in ways that are consistent with, and supported by the evidence.

Hi Carl. I found myself tripping over the early paragraph re the student who has 'read something once and understood 60%.'

You mention that asking this student to close the book and (attempt to) retrieve is 'floundering' rather than learning. However, doesn't this contradict the research?

My understanding of the literature (and my longtime experience with Anki) is that the struggle to retrieve fuzzy, partially-encoded material (i.e., that 60%) is exactly what prevents the 'illusion of competence.' If we wait until encoding is 'secure' (near 100%) before we test, aren't we missing the biggest ROI window for retrieval?

Surely identifying the 40% we don't know via a failed retrieval attempt is more valuable than just re-reading the text?

Essentially, the paragraph seems to go against most of my reading and understanding: that testing is not only good, but is literally learning in-and-of-itself.

Did I misinterpret?

--

P.S. I've just read the Redifer paper, and I'm not sure about it. Asking students to 'free recall' a very heavy/dense 2,500-word academic article after a single 15-minute read seems less like a fair test of retrieval practice and more like a 'working memory torture test' that was destined to cause overload.

There is so much to mine in this piece, but I'll begin with a statement that goes to the heart of the knowledge building vs. strategy instruction debate, which has created a false binary. We use literary works and knowledge-rich texts to guide students toward understanding by engaging them in interpretation, analysis, and synthesis. The knowledge in the piece is the "what" we teach; making sense of it is the "how" we teach.

"An interpretation of a novel, an analysis of historical causation, a synthesis of competing theoretical perspectives; these are not items stored in memory awaiting collection. They must be constructed in the moment, assembled from understanding rather than retrieved from storage."