The Enduring Persistence of Neuromyths in Education

A new study surveying over 3,000 Spanish teachers provides one of the most detailed snapshots to date of educational misconceptions in the field.

These days I work with teachers on how to use evidence to improve learning and part of that work is not just developing a shared understanding of how learning happens, but also how it doesn't, and why certain myths persist in our profession. I don't believe that telling people they're wrong creates change in any meaningful way, or even that evidence can tell you exactly what to do in that classroom, so I approach these conversations with caution. Evidence should empower educators with knowledge to guide professional practice and on the whole, I feel that the profession is moving towards a more evidence-informed culture, yet one study still haunts me.

The Dekker study from 2012 showed that some nine out of ten teachers (yes read that again) believed in the neuromyth of matching teaching to student learning styles. Depressingly, this was not an isolated study and was replicated in subsequent studies. Imagine, for a moment, that nine out of ten doctors still believed that illness was caused by miasma (bad air) rather than bacteria or viruses. We would be appalled; we would question whether medicine as a profession had any meaningful relationship with evidence at all. Yet in education, such widespread endorsement of debunked ideas barely raises an eyebrow.

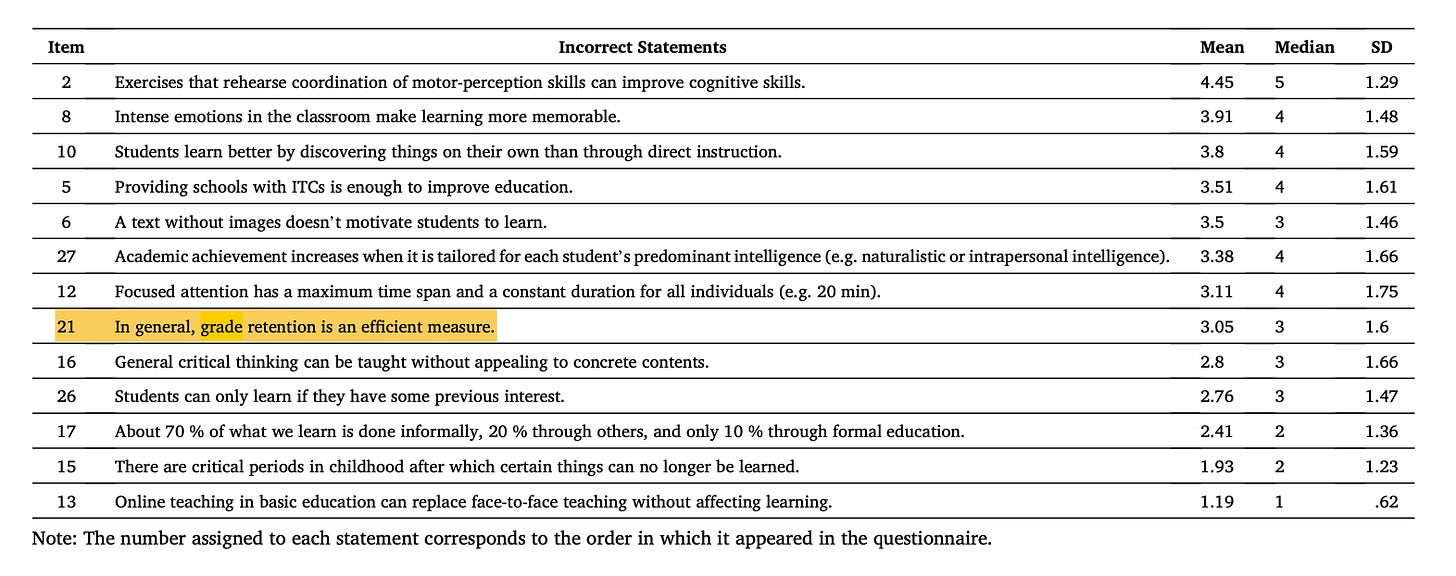

Subsequent research further documented teachers' susceptibility to a range of other neuromyths, but this new study by Juan Fernández and colleagues ventures into new territory, examining misconceptions across the full spectrum of educational practice. Through a systematic review of 189 studies, the researchers identified 27 key statements where there might be a mismatch between what teachers believe and what evidence supports.

The results unfortunately reveal a profession still caught between intuition and evidence. Teachers correctly identified about two-thirds of the statements, but struggled particularly with scientifically unsupported ideas. Most concerning were the high levels of endorsement for practices that could actively harm student learning.

The Most Tenacious Myths

One very interesting finding is that misconceptions aren’t just about the brain, they’re everywhere. Most of us know about your classic neuromyths; learning styles, left–right brain ideas, and so on. What’s striking in this study is that when researchers broadened the scope beyond the brain, they found just as many unsupported ideas about basic teaching methods and day‑to‑day classroom decisions. These aren’t fringe ideas; they are widespread beliefs shaping classroom practice today. Some misconceptions proved especially persistent. The single highest-rated incorrect statement was that exercises which rehearse motor-perception skills can improve general cognition. What does that mean in practice?

It’s the belief that activities designed to coordinate movement and perception (things like balance exercises, clapping rhythms, crawling patterns, cross‑lateral movements or “brain gym” routines) will somehow boost a child’s overall ability to think and learn across subjects. The underlying idea is that by strengthening connections between left and right hemispheres or by rehearsing certain movements, you can sharpen memory, attention, or problem‑solving in general.

This myth is surprising to many because it feels so intuitive: move more and you’ll think better. It’s often wrapped in scientific‑sounding language about “integrating both hemispheres” or “stimulating neural pathways.” But the evidence simply doesn’t support the claim that these motor‑perceptual drills have any broad, transferable effect on cognition beyond the specific skill being practised.

However I would just add that the study's classification of this as a "misconception" requires careful consideration. While it's true that research doesn't support broad cognitive transfer from these specific motor-perception drills, this doesn't negate the legitimate connections between movement and learning that the emerging area of embodied cognition research has established. Physical activity does benefit cognitive function, and movement can enhance specific types of learning, but just not in the way many particular interventions claim.

The real issue is the promise of general transfer, the idea that practising specific motor skills will improve unrelated cognitive abilities. What teachers may be missing is the distinction between movement that supports learning in context versus decontextualised exercises that claim to boost overall brainpower. The high endorsement (4.45 out of 6) suggests teachers find these approaches appealing, possibly because they offer concrete, actionable interventions that feel both scientific and child-friendly.

When Misconceptions Cluster in Mysterious Ways

For me, the most interesting aspect of this study is in its factor analysis.

The authors went beyond simply tallying which myths teachers believe and used statistical modelling to see whether those beliefs cluster into coherent groups. What they found is far more revealing than a simple checklist of errors: teachers’ misconceptions do not fall neatly into content‑based categories.

We might expect all the “brain‑based” myths to sit together, or for progressive pedagogical ideas to align on one factor and more traditional ideas on another. But the data show something stranger. The items do not cluster thematically; instead, they load onto three latent factors that seem to cut across obvious categories.

Take Factor 1, where beliefs about the effectiveness of grade retention (.687), emotional intensity in learning (.527), and the need for explicit reading instruction (.496) unexpectedly sit together. On the surface, these span behaviour policy, affective psychology, and foundational literacy. But perhaps, as you suggest, they reflect a deeper orientation towards “intervention intensity”, a worldview in which strong, decisive actions (whether holding a child back, heightening emotion, or insisting on explicitness) are seen as the engine of learning.

Then look at Factor 2, where the myth that motor‑perception exercises improve cognition (-.661) sits alongside beliefs about the importance of illustrations (-.571) and the efficacy of self‑questioning (.552). These are not thematically aligned either, but they may map onto a deeper tension between embodied, sensory theories of learning and cognitive, metacognitive approaches. In other words, it’s not about topics, it’s about how teachers think learning happens in the first place.

The authors’ analysis suggests that misconceptions are not isolated errors but components of larger mental models: coherent, but often scientifically inaccurate, worldviews about learning. And here’s the worrying implication: Correcting a single myth in isolation may have little impact if the underlying belief system remains intact.

This is why some myths prove remarkably “sticky” despite repeated refutation. They aren’t just facts to be corrected; they are part of a teacher’s professional identity and interpretive lens. For me, this is where beliefs about how learning happens veer into more concerning territory and start to resemble much more entrenched political affiliation or religious conviction.

Metacognitive Blindness

Teachers' failure to recognise that "students are poor judges of their own knowledge" (mean 2.92) reveals a stunning metacognitive blindness. This finding is particularly ironic given that teaching inherently involves constantly assessing what students know versus what they think they know. This blindness may stem from the social dynamics of teaching. Acknowledging student metacognitive failures might feel like undermining student agency or self-confidence. Teachers may also fall victim to the same metacognitive illusions they fail to recognise in students, overestimating their ability to detect when students truly understand material.

Why might this blindness occur? One reason could be the social and emotional dynamics of the classroom. Teachers are trained to nurture confidence and autonomy. Acknowledging out loud that students often don’t know what they don’t know may feel like undermining their agency, or even embarrassing them. There’s a tension between promoting self‑belief and confronting self‑deception.

Another reason may be that teachers themselves share the same metacognitive illusions. Research shows that even experienced professionals overestimate their ability to gauge understanding in others. Teachers may believe they can intuit when a student has grasped a concept, but without systematic checks (retrieval practice, cold calling, probing questions) these impressions are often inaccurate. In other words, teachers’ confidence in their own diagnostic skills may mirror the very illusions their students hold about their learning

The Discovery Learning Illusion

One notable finding was teachers' endorsement of the broad statement that "students learn better by discovering things on their own than through direct instruction" (Item 10, mean 3.8). This belief showed significant variation across educational stages, with nursery educators demonstrating particularly strong agreement.

The study's framing presents this as a misconception, but the reality is more nuanced. The blanket statement fails to acknowledge that discovery-oriented approaches may indeed be developmentally appropriate for young children, where play-based exploration and hands-on investigation are fundamental to how preschoolers naturally engage with their world.

However, the concern emerges when this philosophy extends beyond early years contexts where it's most suitable. The study found that this belief persisted across educational stages, including contexts where more structured, explicit instruction has stronger empirical support - particularly for complex academic content and formal skill acquisition.

The pattern suggests a potential problem: whilst discovery approaches may be entirely appropriate for preschool learning, the broad endorsement of this statement across all educational stages indicates that some teachers may be applying early years philosophies to contexts where students need more guidance and structure.

As a side note, in our new book Instructional Illusions, one of the chapters is dedicated to this persistent belief that novices learn best when discovering things by themselves.

The Cost of Magical Thinking

Why does any of this matter? Because ideas have consequences. When teachers believe that learning should be effortless and natural, they may avoid the kind of deliberate practice that actually builds expertise. When they assume students can reliably judge their own understanding, they may neglect the systematic assessment that guides effective instruction. Most seriously, these misconceptions can perpetuate educational inequality.

Discovery learning might work for middle-class children who arrive at school with extensive vocabulary and background knowledge. But for disadvantaged students, it can be a form of educational malpractice, expecting them to reinvent what others learned through cultural osmosis, perpetuating rather than reducing educational inequality.

How might we address this mismatch between belief and evidence? The researchers suggest several approaches: improving scientific literacy among teachers, strengthening knowledge about research methods, and creating better mechanisms for translating research into practice. But we might also need to examine our own assumptions about what makes teaching feel right. Perhaps the most effective practices don't always align with our intuitions about learning. Perhaps the methods that work best are not always the ones that make us feel that they work.

This doesn't mean abandoning our values or treating children as empty vessels. But it does mean recognising that good intentions are not enough, that feeling right is not the same as being right, and that the most caring thing we can do for students is to use approaches that actually help them learn.

The teachers in this study are not uniquely susceptible to error. They are simply human beings working in a complex profession with limited feedback about the long-term effects of their practice. But their misconceptions cost real students real opportunities for learning. In education, as in medicine, we owe it to those we serve to base our practice on evidence rather than ideology, on what works rather than what feels good.

This post is based on "Beyond neuromyths: Examining in-service teachers' misconceptions about teaching and learning" by Juan G. Fernández, Agustín Martínez-Molina, Miguel A. Vadillo, and Marta Ferrero, published in Teaching and Teacher Education (2025).

I see that your book is not going to be available through Amazon in the US. How might I get a copy once it's released, Carl? Your work is sooooooo damn important!

In Listening to the Experts Doesn't Mean Giving Them the Last Word: Separating science from sentiment (https://harriettjanetos.substack.com/p/listening-to-the-experts-doesnt-mean?r=5spuf), I scratch the surface of what you so elegantly present in this piece--which, If I'm being honest, feels a bit like being savaged by a teddy bear. That is your great gift: giving us teachers hard truths but soft landings. (I well remember working with learning styles!) Thank you!