The "Embarrassingly Parallel" Problem: When Students Understand the Parts But Not The Whole

On the difference between learning that scales and learning that doesn't, and what a concept from computer science can teach us about where educational technology succeeds and where it reliably fails.

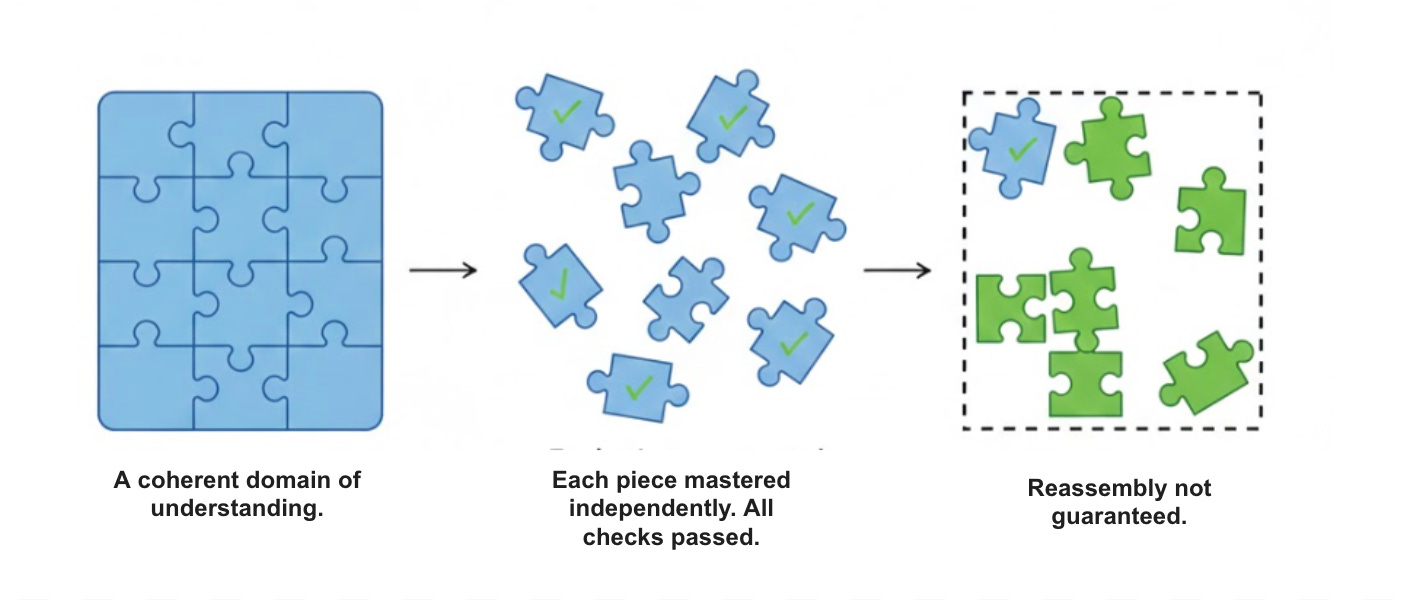

If there is a central conundrum in instructional design, it is this: firstly, how to disassemble a domain of knowledge into teachable parts without destroying what made it a domain in the first place. And then secondly, how to reassemble those parts into flexible understanding without mistaking performance on individual components for comprehension of the whole.

For example, a student can learn the dates of every major battle in the First World War, define "alliance" and "imperialism," and correctly identify the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as the triggering event, yet still have no real understanding of why the war happened. Or more commonly, the student who can accurately define a set of vocabulary words and still be unable to use them appropriately in speech or writing.

What makes this conundrum so persistent is that the two problems; decomposition and reassembly, look superficially similar but are structurally different. The first lends itself to analysis, optimisation, and scale. The second depends on sequencing, connection, and judgement, and resists being reduced to a set of independent operations. One of the reasons education keeps getting this wrong, I suspect, is that we lack a precise language for describing the difference.

One of the more unexpected parts of my work lately has been collaborating with software engineers and developers on learning apps. It’s been fascinating working with people from a different field, not because they “do education differently” in some vague way, but because they force you to make your assumptions explicit. Engineers think in constraints: what can be decomposed, what can be measured, what can be scaled. And when those constraints meet the science of learning, you get clarity, albeit sometimes of the uncomfortable kind.

Yesterday I was working with a developer on a vocabulary app and he used a phrase I hadn't encountered before. We were discussing vocabulary as knowledge components and how the system could deliver individualised practice to thousands of students simultaneously, and he said, "Well, that's what we call an embarrassingly parallel problem."

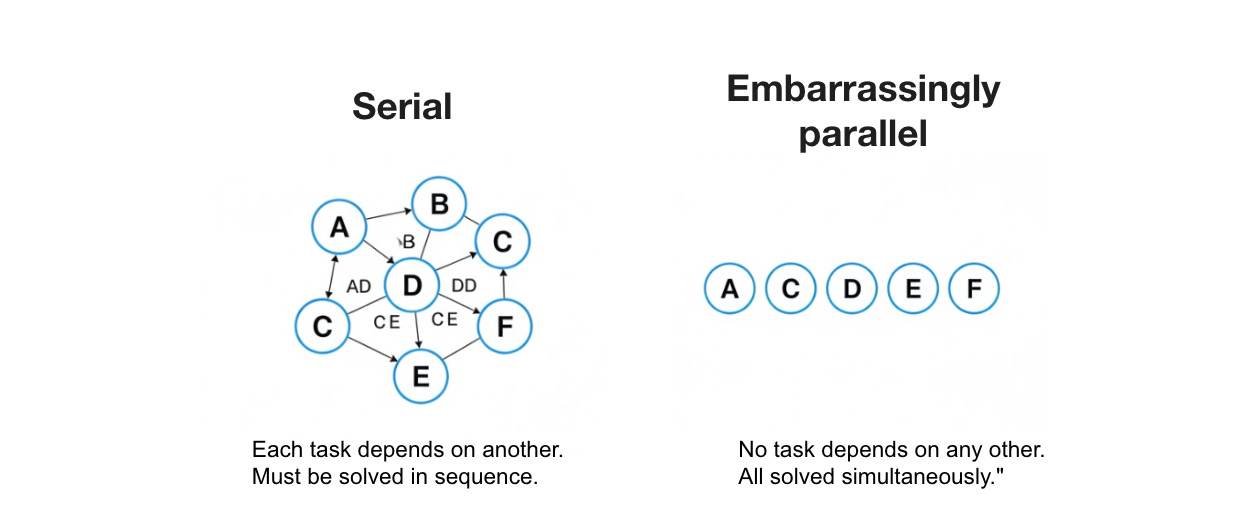

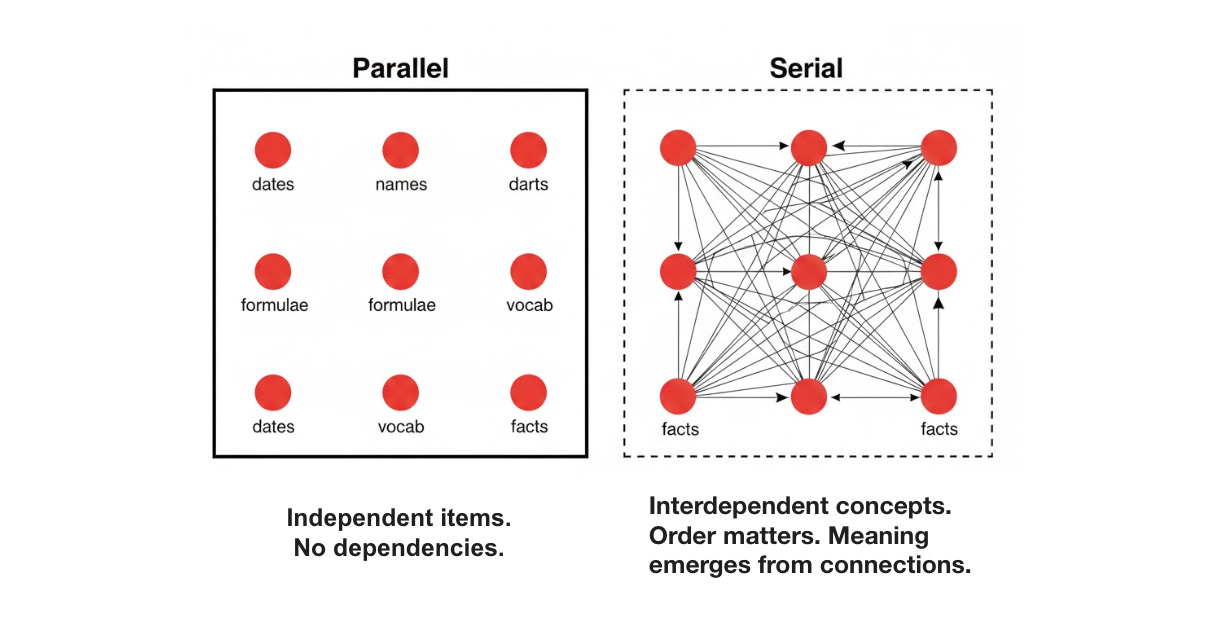

I’d never heard that before and asked him to explain. In computer science, an “embarrassingly parallel” problem is one that can be broken into completely independent sub-tasks, each solvable at the same time with no communication or coordination between them. To “parallelise” a problem then, means to break it into multiple parts that can be worked on at the same time, rather than in sequence, without one part needing the results of another. The opposite is "serial" or "sequential" processing, where task B cannot begin until task A has finished, task C cannot begin until task B has finished, and so on.

The word “embarrassingly” carries a sort of self-deprecation: some problems are almost too easy to parallelise because there are no dependencies, no sequencing constraints, no need for one process to wait on another. Rendering millions of pixels in an image, running the same simulation with different parameters, sorting independent records: each unit of work proceeds in blissful ignorance of its neighbours.

The phrase stuck with me because it seemed to illuminate something important about both the promise and the peril of trying to apply what we know about learning to educational technology, and about a distinction that cognitive psychology has been circling for decades without quite naming it in these terms.

Breaking Knowledge Without Breaking Meaning

If there was a central conundrum in instructional design, I would say it is the question of how you a) decompose knowledge domains into components small enough to teach to novices and b) reassemble those components into something that resembles the integrated, flexible understanding that made the domain worth teaching in the first place.

In education we would call this curriculum design and a core part of the ‘knowledge-rich’ approach. And as Christine Counsell notes in a recent essay, a knowledge-rich curriculum must do more than list disconnected items, it must “ask not only ‘What is the ambitious expertise we want our students to leave us with?’ but also ‘What are the most effective steps to help our students to develop this expertise?’”, emphasising careful sequencing and practice if understanding is to emerge rather than mere component mastery.

The decomposition of knowledge is necessary because novices cannot apprehend the whole all at once; working memory will not permit it. But the reassembly is where instruction most reliably fails, because the connections between components are not themselves components. They are relationships, contingencies, contextual judgements; the mortar, not the bricks. And no amount of optimising the bricks will produce a wall.

The Parallel Layer: What Scales Easily in Learning

There is a sense in which much of what we know about effective learning exploits genuinely parallel processes. Retrieval practice strengthens individual memory traces. Spaced repetition exploits consolidation mechanisms that operate on discrete items. Immediate feedback corrects specific misconceptions at the point of error. Vocabulary can be drilled word by word. Multiplication tables can be practised fact by fact. These processes are, in a meaningful sense, embarrassingly parallel: they can be run simultaneously across thousands of learners, each operating independently, with no degradation in quality.

This is precisely why intelligent tutoring systems scale so well, with no degradation in quality. Because each learner’s feedback loop operates as an independent process, personalised practice and feedback can be delivered to tens of thousands of students simultaneously. Large-scale randomised controlled trials have found modest but reliable effects on standardised tests, with substantially larger gains for lower-attaining students, often equivalent to close to a year of additional progress. And the costs are strikingly low. This is the economics of embarrassingly parallel processing applied to education: marginal costs approaching zero, with impact distributed across vast numbers of learners at once.

Spaced repetition systems like Anki work on the same principle. Each flashcard is an independent thread. The algorithm optimises the spacing for each item without reference to any other. The system does not need to know that the student is also learning French irregular verbs while reviewing anatomy terms; each item is its own self-contained process. And the evidence for spaced practice is robust: a recent meta-analysis of classroom studies found effect sizes of 0.54 SD, with seven-day intervals proving consistently effective.

What’s interesting to me is that the parallel layer is not standing still; it is getting substantially more sophisticated. There is a lot going on in the spaced repetition scheduling field which illustrates this perfectly. Until recently, most systems used an algorithm called SuperMemo-2, developed by a college student in 1987 based on his personal experiments. It was somewhat arbitrary: see a card after one day, then six days, then apply an exponential backoff. Get it wrong and you reset to day one. The implicit assumption was that the forgetting curve for every piece of knowledge is roughly the same, which is not true at all.

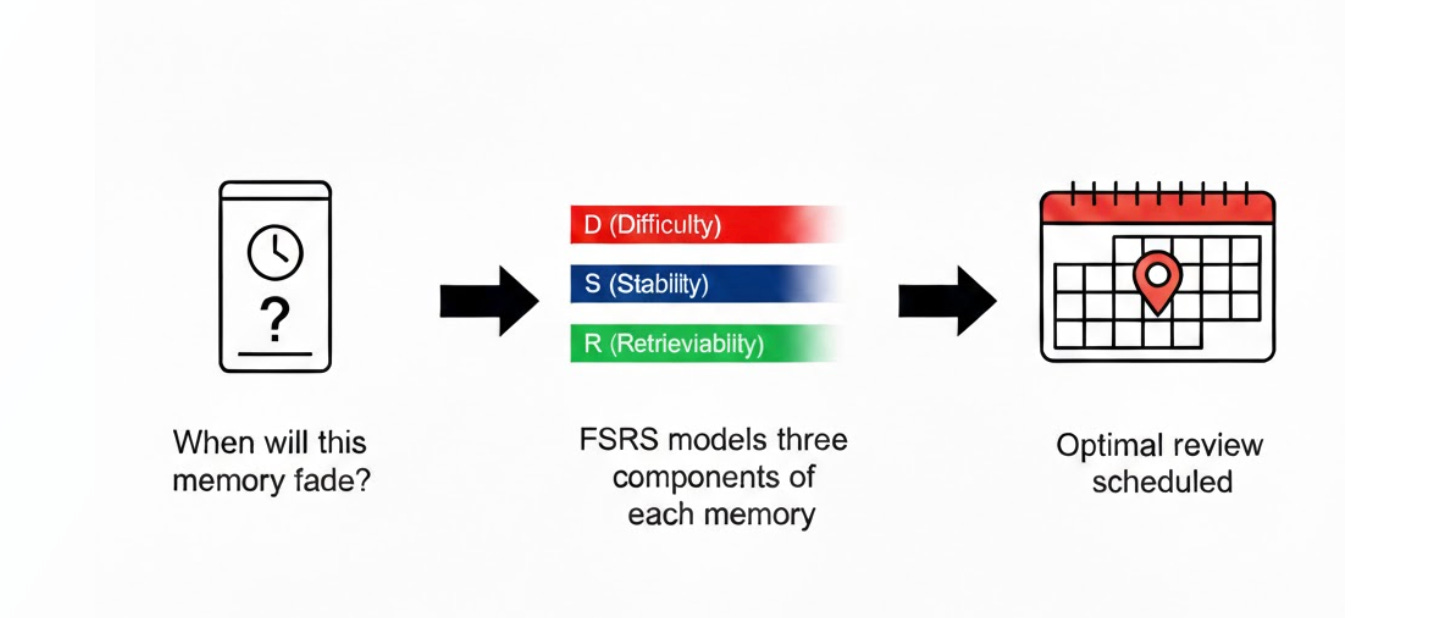

However, a new algorithm called FSRS (Free Spaced Repetition Scheduler), developed by Jarrett Ye, has replaced this blunt instrument with something far more precise. FSRS is built on a “Three Component Model of Memory” which holds that three variables are sufficient to describe the status of a unitary memory: retrievability (the probability that you can recall an item at a given moment), stability (how long, in days, it takes for that probability to drop from 100% to 90%), and difficulty (how hard it is to increase a memory’s stability after each review). Each card has its own values for these three components, collectively known as its “memory state.”

Using machine learning trained on several hundred million reviews from around 10,000 users, FSRS calculates 21 parameters that model how these three variables interact, and it can be further optimised against a learner’s own review history to fit their personal forgetting curves. The result is a system that can predict with considerable accuracy when a learner’s recall probability will drop to a specified threshold, and schedule the review accordingly. Users can set their desired retention rate (say 90%, or 70% to reduce workload), and FSRS will calculate the optimal intervals to achieve it. Compared to Anki’s legacy algorithm, FSRS requires 20 to 30% fewer reviews to achieve the same level of retention. Even with default parameters, before any personalisation, it outperforms the old approach.

This is seriously impressive, and it represents the parallel layer operating at its most refined. Each card is basically an independent prediction problem, optimised without reference to any other card, and machine learning makes that optimisation far more efficient than any hand-crafted formula could. The parallel infrastructure of learning is getting better, and that is worth celebrating.

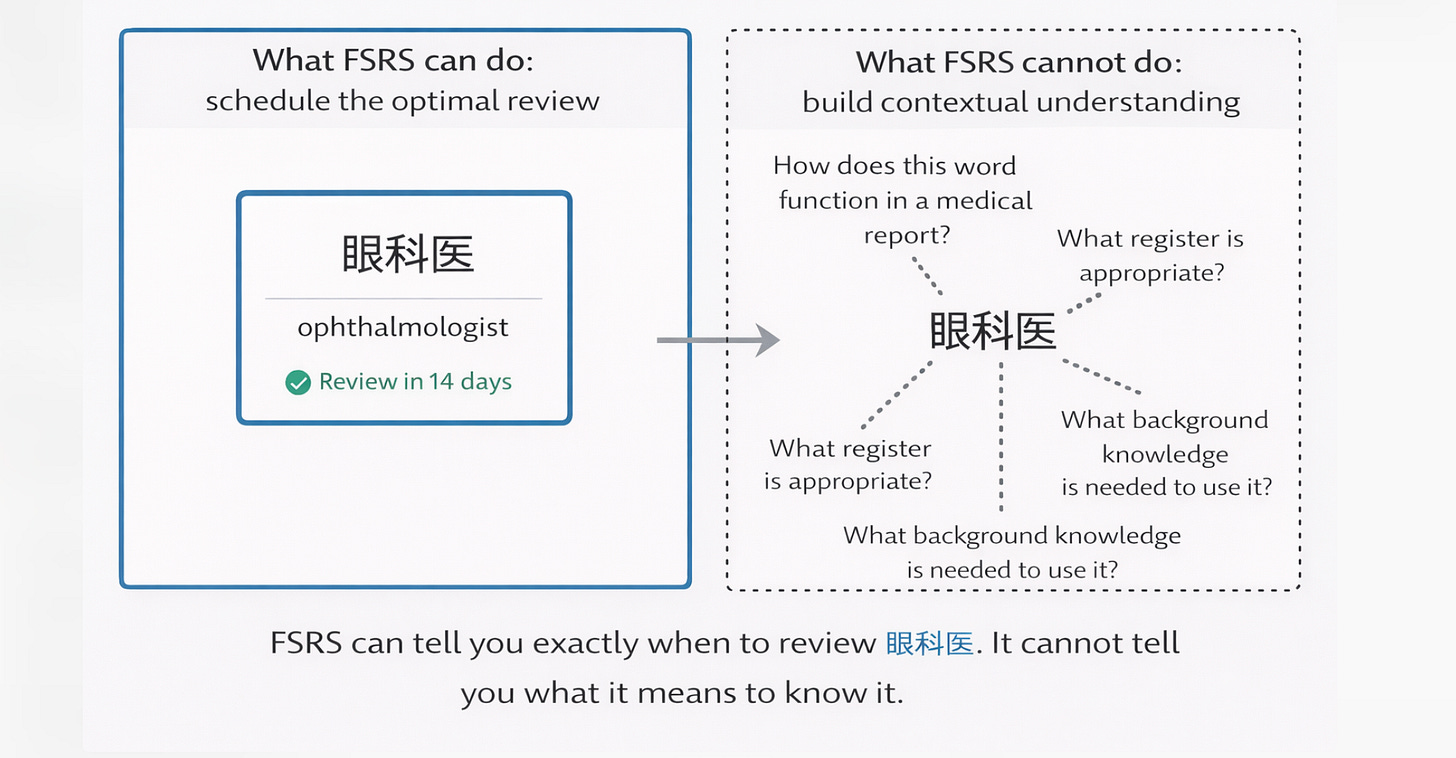

But it also sharpens the question at the heart of designing effective learning. For exampole, FSRS can tell you exactly when to review the Japanese word 眼科医 (ophthalmologist), but it cannot tell you how that word functions differently in a medical report versus a casual conversation, how it relates to the broader semantic field of Japanese medical terminology, or how it interacts with the grammatical structures required to use it in a coherent sentence.

The algorithm optimises the retention of isolated items with extraordinary precision. What it does not, and cannot, address is the integration of those items into the kind of flexible, context-sensitive knowledge that constitutes actual competence.

In other words, you can memorise 3,650 words a year in twenty minutes a day. But knowing 3,650 isolated words is not the same as reading a novel, following a conversation, or writing a paragraph. Those require precisely the serial, integrative processes that no scheduling algorithm touches.

Ok. So far, so good, and so….well, limited. The parallel layer of learning is real, it is well-evidenced, and technology serves it brilliantly. The question is what happens next.

The Serial Layer: What Cannot Be Parallelised

But here is where the whole thing becomes truly interesting and problematic, because it forces us to confront what learning is not. In computer science, the problems that are not embarrassingly parallel are those where sub-tasks are interdependent: where one process must wait for another, where outputs become inputs, where the order of operations matters and cannot be rearranged without corrupting the result. The overhead required to manage these dependencies is called coordination cost, and it is often the binding constraint on performance.

Learning, at its most meaningful, is emphatically not embarrassingly parallel. To understand the causes of the First World War is not to hold a collection of independent facts, each stored and retrievable in isolation, but to grasp a web of interdependencies: alliances, economic pressures, nationalist ideologies, contingent decisions, structural forces. Each node in this web derives its meaning from its connections to the others. You cannot parallelise the construction of such understanding any more than you can build the tenth floor of a building before the ninth.

Again, Herbert Simon’s concept of “near decomposability” is helpful here. Complex systems, Simon argued, can be partially broken down into sub-systems, but those sub-systems still interact at their boundaries. A curriculum is near-decomposable: you can teach phonics and handwriting in relative independence, but reading comprehension depends on vocabulary, which depends on background knowledge, which depends on prior reading, which depends on the very comprehension you are trying to build. These are serial dependencies. They have an order and they resist parallelisation.

The Measurement Signal Problem

The evidence base for educational technology contains a signal that, viewed through this lens, becomes remarkably clear. Across multiple meta-analyses and large-scale evaluations, effect sizes on curriculum-aligned tests are consistently two to three times larger than effect sizes on standardised tests. Kulik’s meta-analysis of mastery learning found 0.50 SD on experimenter-made tests but only 0.08 SD on standardised measures. A tutoring meta-analysis found 0.84 SD on narrow tests versus 0.27 SD on standardised assessments. This pattern is ubiquitous.

The conventional explanation is test-curriculum alignment: students perform better on tests that closely match what they were taught. This is obviously true, but it is not the whole story. What curriculum-aligned tests measure is whether the parallel processes worked; whether students acquired the targeted skills, memorised the targeted facts, mastered the targeted procedures.

What standardised tests measure, however imperfectly, is whether those acquisitions have been integrated into something more flexible; whether the student can apply knowledge in contexts not explicitly rehearsed, make inferences across domains, transfer understanding to novel problems. In other words, the gap between aligned and standardised test scores is not merely a measurement artefact. It is a signal. The parallel layer is working. The serial layer is not being adequately served.

The Atomisation Trap: When the Whole Never Reappears

The great temptation of educational technology, (and it is a temptation born of genuine success), is to optimise for what is measurable and “parallelisable” at the expense of what is neither. When a platform can demonstrate that students have mastered 47 discrete skills with 85% accuracy, it is natural to conclude that learning has occurred. And in a sense it has, but mastering 47 discrete skills is not the same as understanding the domain those skills inhabit. The parts have been acquired; the whole has not been assembled.

This is what we might call the atomisation trap: the reduction of a curriculum to its “embarrassingly parallel” components, optimised independently, measured independently, and never reconstituted into any kind of coherent understanding. It produces students who can pass skill checks but cannot write a sustained argument, who can solve practiced problem types but freeze when the problem is reframed, who know the dates but cannot explain why they matter.

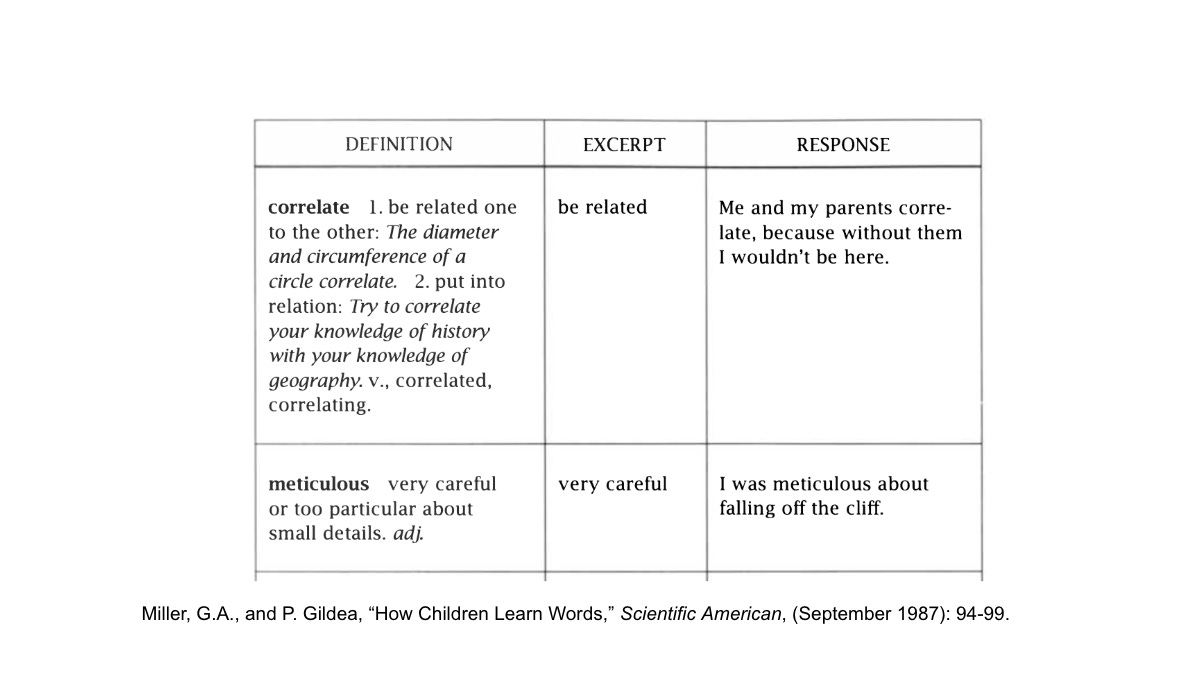

An example of this I am fond of using is from a study by George Miller and Patricia Gildea, published in Scientific American in 1987 in which children were given dictionary definitions of words and asked to use them in sentences. The results were technically correct at the component level but semantically absurd when used in a sentence. One child, having learned that "correlate" means "be related," wrote: "Me and my parents correlate, because without them I wouldn't be here." Another, told that "meticulous" means "very careful," produced: "I was meticulous about falling off the cliff."

Each child had successfully completed the parallel operation: definition retrieved, synonym matched, sentence generated. But the serial layer, the contextual understanding of how a word actually functions in living language, was entirely absent. The parts had been acquired. The whole had not been assembled. This is the atomisation trap in miniature: every component mastered, but no guarantee they recombine into understanding.

The evidence from ALEKS, an adaptive learning platform, is instructive here. When ALEKS replaces traditional instruction entirely, the effect is essentially zero (Hedge’s g = 0.05). When it supplements teacher-led instruction, the effect is a meaningful 0.43. The parallel processing of the platform, its adaptive diagnostics, its individualised practice, its immediate feedback, all of this works. But it works only when there is a human being providing the serial layer: the sequencing, the connecting, the contextualising, the building of one idea upon another in a way that the platform cannot do because it was not designed to do it.

As I’ve written about before, Carnegie Learning’s MATHia is one of the more sophisticated attempts to address this. Its cognitive models track dependencies between skills, not just mastery of isolated components, using production rules that represent the relational structure of mathematical knowledge. Its blended approach, combining the platform with teacher-led instruction, nearly doubled growth on standardised tests compared to traditional curricula alone. The system is effective precisely because it does not treat mathematics as embarrassingly parallel; it respects the serial dependencies between concepts while exploiting parallel infrastructure for practice and feedback.

What Scales and What Doesn’t

There is a deeper lesson here about why educational interventions so reliably lose potency at scale. Kraft and colleagues found that tutoring studies with fewer than 100 students average d = 0.38, while programmes with over 2,000 students average d = 0.11: a 66% reduction. The Harvard study of GPT-4 based tutoring achieved extraordinary effects of 0.73 to 1.3 SD, but with only 194 students. No one has replicated anything close to that at scale.

The embarrassingly parallel framing explains why. Scaling the parallel layer is trivial: if the software works for 200 students, it works for 200,000. The marginal cost is negligible. But scaling the serial layer, the human infrastructure of professional development, school culture, teacher knowledge, instructional leadership, adaptive response to context, is not embarrassingly parallel at all. Each school has its own dependencies. Each teacher requires individual support. Each classroom context demands coordination that cannot be automated away.

Achievement Network, an assessment platform, provides a decent example. In high-readiness schools, those with supportive culture and strong leadership, the intervention produced 0.18 SD gains. In low-readiness schools, it produced nothing. The technology was identical. The parallel layer was the same. What differed was the serial layer: the human capacity to take data and weave it into coherent instructional response.

Parallel Delivery, Serial Understanding

This whole concept of “embarrassingly parallel” problems crystallised something I had been thinking about for a long time. The science of learning has identified powerful mechanisms; retrieval practice, spacing, feedback, interleaving, worked examples etc. that genuinely operate with a degree of independence and can be delivered in parallel at scale via technology which serves this layer extraordinarily well, and the evidence is clear that it works.

But deep understanding is not embarrassingly parallel. It is painstakingly serial: built connection by connection, layer by layer, in a process that requires time, sequence, and the kind of integrative thinking that no algorithm yet replicates. The mistake is not in building platforms that exploit the parallel layer; the mistake is in believing that the parallel layer is all there is.

The best educational technology respects this distinction. It parallelises what can be parallelised: the delivery, the feedback, the scheduling, the data collection, the routine practice. And it preserves, protects, and supports what cannot: the teacher’s capacity to sequence ideas, to connect the dots between isolated skills, to build the kind of coherent understanding that transfers beyond the platform and into the world.

The developers I am working with are part of Alpha School and their model is one that is seriously working on these problems. The idea is deceptively simple: if technology is exceptionally good at delivering the parallel layer (diagnosis, retrieval practice, spacing, interleaving, feedback, scheduling) then its role should be to make that layer as efficient and reliable as possible, while deliberately preserving the “serial” work of integration support for a human being. This support comes in the form of guides who provide the human scaffolding that technology cannot: mentoring, motivation, tutoring when needed, and the steady support required to keep students engaged in the longer, serial work of understanding.

What is interesting about this model is that it does not attempt to automate the hardest part of instruction. Instead, it acknowledges it. Alpha’s guides exist precisely because understanding does not scale in the same way that practice does. The system scales the parallel layer aggressively, while concentrating scarce human attention where it matters most. I have seen these guides in action and the care and attention they provide students is phenomenal, and on a level that is virtually impossible for most teachers.

There’s been a gradual acceptance for some time now that what we are expecting classroom teachers to do is beyond what can be reasonably expected, and this is reflected in the current recruitment and retention crisis. The expectation of managing thirty or more students simultaneously, each at a different point of understanding, each with different misconceptions, each requiring the kind of sustained, responsive attention that is, by its very nature, serial: one conversation at a time, one connection at a time, one moment of recognition at a time.

The vocabulary app and others I’m working on have really made me think hard about this problem of parallel vs serial. The drilling of individual words is genuinely embarrassingly parallel, and the scheduling of those drills is now being refined by machine learning algorithms like FSRS that can predict with remarkable accuracy when a learner is about to forget a specific item. That precision is a gift; it means we can build the parallel layer with a confidence and efficiency that would have been unimaginable even five years ago.

But vocabulary acquisition in the deeper sense; understanding how words relate to one another, how they shift in register and connotation, how they unlock comprehension of increasingly complex texts, that is a serial process. It requires context, connection, and the slow, patient work of building a mind that knows not just the parts, but how the parts compose a whole. No scheduling algorithm, however sophisticated, will provide that. It has to be designed into the instruction itself: the sequencing of words within semantic fields, the embedding of new vocabulary in meaningful texts, the explicit teaching of morphological relationships and contextual variation. This is the work of instructional design, where the goal is not to make learning embarrassingly parallel. It is to know which parts already are, exploit them brilliantly, and never mistake them for the whole.

This parallel and serial issues reminded me of Genie-The Wild Child and the difficulty she had with language development. After rescuing her from the severe neglect she was able to be taught hundreds of words and could identify objects, yet she remained unable to effectively communicate. Language is not just the memorization of words, but the ability to string together words using proper syntax and pragmatics. Vygotsky would suggest she lacked the necessary social component necessary for learning. Ed tech seems to be better suited for the parallel learning, but scaffolding and human interaction are necessary for stringing concepts together.

How is learning a skill different from learning information? Beginning reading and writing skills can be sequenced, or not.

But even if they are sequenced and "connected", it's still parallel right? they need to be practiced in a meaningful way. Could this be compared to phonics and comprehension? Grammar and writing interesting sentences?

It seems like we're talking about a 3 step thing: first from random skills or information, second to connected skills or information, third to a bigger context or meaning. Am I on the right track here?