The Algorithmic Turn: The Emerging Evidence On AI Tutoring That's Hard to Ignore

Are We Approaching A Turing Test for Teaching?

In The Emperor’s New Mind, physicist Roger Penrose proposed a radical idea: that consciousness does not obey the known laws of physics. Human understanding, he argued, may arise from processes beyond algorithmic computation, moments of genuine insight that no machine could reproduce because they are not merely calculable.

Penrose’s claim remains controversial. Most scientists reject it, insisting that cognition, like all biological processes, obeys the laws of nature. But his provocation endures because it forces a deeper question: if consciousness cannot be computed, can it be taught? And if it can, does that mean learning obeys the same physical laws that govern everything else?

Since the mainstream emergence of LLMs two years ago, I’ve found myself wrestling with two disturbing questions: Firstly, does learning itself obey the laws of material reality, or does it resist them? And secondly, if it obeys them, then does the emergence of artificial intelligence mean that teaching itself is fundamentally algorithmic, that what we’ve long considered an irreducible human art is actually a computable process? Not just faster, or cheaper, or more scalable, but genuinely more effective at producing learning?

The optimistic vision is compelling: every child receives expert, tireless, infinitely patient instruction calibrated precisely to their needs. The achievement gap narrows because the students who most need help finally get it, not in sporadic bursts but continuously, systematically. Teachers are freed from the grinding mechanics of delivery and assessment to focus on what machines genuinely cannot do: motivation, relationship, the human dimensions of learning.

But there’s a darker reading of AI, one I think we should take seriously. If teaching becomes demonstrably algorithmic, if learning is shown to be a process that machines can master, then Penrose’s ghost returns with a different question: what does it mean for human expertise when the thing we most value about ourselves, our ability to understand and to help others understand, turns out to be computable after all? Not insight, but instruction. And if instruction is algorithmic, then what exactly is left that makes human teachers irreplaceable?

What is the Actual Evidence for AI Tutoring?

I’ve been sceptical about Edtech for the majority of my career in education, where the story of EdTech has largely been one of expensive failure. But something has shifted. Not the rhetoric, which remains as breathless as ever, but the emerging evidence.

A recent study from Harvard University caught my attention and provides perhaps the most rigorous evaluation of GPT-4-based tutoring to date, and what makes it significant is not merely its findings but what it measured against. In a randomised controlled trial with 194 undergraduate physics students, a carefully designed AI tutor outperformed in-class active learning, the kind of research-informed pedagogy that has been demonstrated over decades to substantially outperform traditional lectures.

This was not a comparison against passive instruction or weak teaching (as many studies are), but against well-implemented active learning delivered by highly rated instructors in a course specifically designed around pedagogical best practices. The AI tutor produced median learning gains more than double those of the classroom group.

To the best of my knowledge, these are some of the highest rigorously documented effects for any AI tutoring system, with what might be described as overwhelming statistical significance (which makes me very skeptical). Perhaps more striking still, 70% of AI students completed the material in under 60 minutes (median 49 minutes) compared to the 60-minute classroom session, with no correlation between time on task and learning, suggesting efficiency gains alongside effectiveness.

Now before we get carried away, this is a single study at one elite institution in a specific domain (introductory physics), with a sample of fewer than 200 students. The AI tutor was provided with step-by-step solutions to prevent hallucinations, meaning the study tested whether AI could deliver pre-scripted content effectively rather than whether it could solve physics problems independently.

Second, the AI tutor worked best as students’ first substantial engagement with challenging material. It was designed to bring students up to a level where they could then benefit maximally from in-class instruction focused on advanced problem-solving, project-based learning, and collaborative work. This is essentially a flipped classroom model, not a wholesale replacement of classroom teaching.

Third, the effectiveness depended on careful engineering of the system. Students cannot simply use ChatGPT or any other off-the-shelf AI tool and expect comparable results. The system was built by instructors who understood both the content and the pedagogical principles that promote learning. This required significant time and expertise.

Fourth, we don’t yet know how such systems perform over an entire course, or what effects they might have on other important outcomes like collaboration skills, scientific identity, or long-term retention.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, this study took place in a context where students had access to expert instruction, course staff, and peer collaboration. The AI tutor supplemented human teaching; it did not replace it. The proper comparison is not “AI versus teachers” but rather “AI-supported instruction versus conventional instruction.”

The Direction of Travel: Is This Time Different?

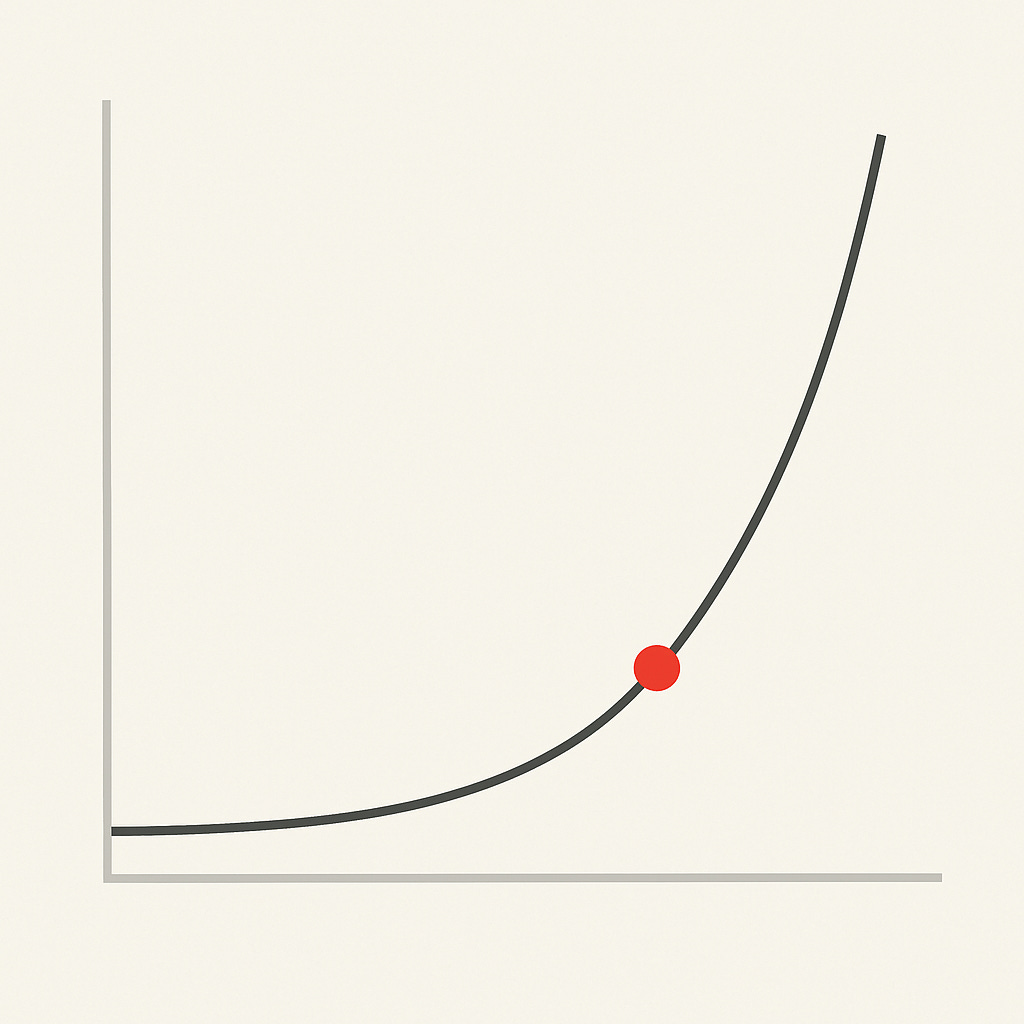

Nevertheless, what strikes me is not where AI tutoring stands today, but where the trajectory points. Most educational interventions are essentially static. Reduce class sizes to fifteen and the effect remains constant; implement retrieval practice and the gains stay roughly the same etc. These are fixed interventions with broadly stable effect sizes. But what’s happening with AI is different.

The Harvard study was conducted using GPT-4 in autumn 2023; by the time the paper was published in 2025, the underlying technology had already advanced. If AI tutoring can produce effect sizes of 0.73 to 1.3 standard deviations now, whilst still requiring pre-written solutions and careful scaffolding to prevent errors, what happens when the models can reason through physics problems independently? When they can diagnose misconceptions in real time? When they can adapt not just to individual students but to culturally specific contexts?

The question is not whether this study replicates, (though that matters). The question is what education looks like when the technology underpinning it improves exponentially whilst our understanding of how humans learn remains, by comparison, nearly static.

What if an AI tutor could mimic the learning experience one would get from an expert (human) tutor? It could address the unique needs of each individual through timely feedback while adopting what is known from the science of how students learn best. 1

And the Harvard study is not an isolated finding. ASSISTments, a mathematics tutoring platform evaluated across two large-scale randomised controlled trials involving thousands of students, achieved effect sizes of 0.18 to 0.29 standard deviations on standardised tests, with the largest gains for struggling students, earning it the highest ESSA Tier 1 evidence rating at a cost of less than £100 per student. Carnegie Learning’s MATHia, tested with over 18,000 students across 147 schools, produced effect sizes ranging from 0.21 to 0.38 standard deviations.

Long before the emergence of ChatGPT, VanLehn’s comprehensive meta-analysis found that well-designed intelligent tutoring systems produce effect sizes of 0.76 standard deviations compared to no tutoring, and crucially, the difference between these systems and human tutors was a mere 0.21 standard deviations, small enough to be statistically insignificant in many comparisons. A large randomised controlled trial known as Tutor CoPilot found that school pupils whose tutors used an AI assistant achieved significantly higher mastery rates than those in the control group, with the biggest gains among the least experienced human tutors.

Yet there is a troubling paradox at the heart of AI tutoring. The very same technology that can produce effect sizes above 0.7 standard deviations can also make students demonstrably worse at learning. And I would argue that the harmful version is the one most students are currently using today.

The Illusion of Understanding: When AI Harms Learning

So the evidence for well-designed AI tutoring systems is, in a certain light, compelling. But there is a darker truth that sits uncomfortably alongside it: many uses of AI in education actively harm learning.

Firstly, as Laak and Aru have recently argued, AI systems are made for efficiency, not education. They are designed to optimise task completion, minimise friction, and deliver immediate, seemingly correct answers; all virtues in engineering, but vices in learning. LLMs are engineered for user-friendly problem-solving, not for the cognitively effortful process through which understanding is built.

LLMs are engineered for frictionless and user-friendly task completion, not for the friction-filled process of learning.2

Recent research is beginning to quantify what teachers have long suspected: when AI does the thinking, students stop doing it themselves. In a 2025 mixed-methods study published in Societies, Michael Gerlich found that frequent AI tool use was strongly negatively correlated with critical thinking ability, largely because of a mechanism known as cognitive offloading. The more participants relied on AI to remember, decide, or explain, the less capable they became of reasoning independently. Younger users (those most immersed in generative tools) showed the greatest decline. Gerlich describes this as a kind of “cognitive dependence”: efficiency rising as understanding falls. It’s precisely this frictionless fluency that creates the illusion of learning; the sense that one is mastering material when, in fact, the machine is doing the mastery.

This is not a peripheral concern. A rigorous study from the University of Pennsylvania involving high school mathematics students found that unrestricted access to generative AI without guardrails significantly harmed learning outcomes. Students with AI access performed worse on subsequent assessments than those who worked through problems unaided. The mechanism is straightforward: when the AI provides solutions on demand, students bypass the very cognitive processes that build understanding. They mistake fluent AI-generated explanations for their own comprehension, a metacognitive error with serious consequences.

The distinction between AI systems that enhance learning and those that destroy it is not about the underlying technology; GPT-4 powered both the highly effective Harvard tutor and the ineffective tools students use to avoid thinking. The difference lies entirely in design. The Harvard system was engineered to resist the natural tendency of LLMs to be maximally helpful. It was constrained to scaffold rather than solve, to prompt retrieval rather than provide answers, to increase rather than eliminate cognitive load at the right moments.

ChatGPT, by contrast, is optimised for frictionless task completion. It will happily write your essay, solve your equation, explain the concept you should be puzzling through yourself. It is designed to be helpful, not to promote learning, and those are fundamentally different objectives.

This creates a profound challenge for education systems. The same technology can produce effect sizes above one standard deviation or actively harm student outcomes, depending entirely on how it is deployed. Teachers cannot simply “use AI”; they must understand the difference between AI as cognitive prosthetic and AI as cognitive offload. The former extends what students can do by supporting the processes that build capability; the latter atrophies those processes by replacing them. One is a scaffold that can eventually be removed; the other is a crutch that makes walking without it progressively harder.

The Limits of Learning Science and AI

A big problem with existing learning science is that it provides surprisingly little guidance at the level of granularity required. Academic research operates at the level of constructs and principles: (manage cognitive load, dual code, retrieve information, promote metacognition, etc.) But translating these principles into specific model behaviours, into turn-by-turn decisions about when to prompt and when to tell, when to increase difficulty and when to provide support, remains largely uncharted territory.

What has become clear is that LLMs designed for education must work against their default training. They must be deliberately constrained to not answer questions they could easily answer, to not solve problems they could readily solve. They must detect when providing information would short-circuit learning and withhold it, even when that makes the interaction less smooth, less satisfying for the user. This runs counter to everything these models are optimised for. It requires, in effect, training the AI to be strategically unhelpful in service of a higher goal the model cannot directly perceive: the user’s long-term learning.

The implications are sobering. If many current uses of AI in education are harmful, and if designing systems that enhance learning requires sophisticated understanding of both pedagogy and AI behaviour, then the default trajectory is not towards better learning outcomes but worse ones. Students already have unrestricted access to tools that will complete their assignments, write their essays, solve their problem sets. They are using these tools now, at scale, and in most cases their teachers lack both the knowledge to distinguish harmful from helpful uses and the practical means to prevent the former. The question is not whether AI will transform education. (It clearly already is). The question is whether that transformation will make us smarter or render us dependent on machines to do our thinking for us.

The Knee In The Curve

But these flaws are not going to stay flaws forever. Minimally guided instruction like pure discovery learning was a bad idea that didn’t work in the 1950s and it’s still a bad idea that doesn’t work in 2025.

However, evolutionary progress, Kurzweil argues, is exponential because of positive feedback: each stage uses the results of the previous stage to create the next. This growth appears deceptively flat at first, what he calls the period before “the knee in the curve, before rising almost vertically. More crucially, the process becomes super-exponential when success attracts resources; the computer chip industry exemplifies this dynamic, where the fruits of exponential growth make the sector an attractive investment, and this additional capital fuels further innovation, creating what amounts to double exponential growth.

In theory, AI tutoring is exhibiting these characteristics. Each interaction generates data; that data improves the model; improved performance attracts more users and investment; greater resources enable more sophisticated development; better AI tutors produce better results; superior results draw more adoption and funding.

Unlike human tutoring, where improvements spread slowly through training programmes and institutional change, AI improvements propagate instantaneously across millions of students. A breakthrough discovered whilst tutoring one student in Singapore becomes available to every student everywhere within hours.

We may currently be in the flat part of the curve, where AI tutors still lag behind skilled human tutors in various dimensions. But the trajectory is clear, and the mechanisms are in place. The question is not whether AI will eventually provide more effective instruction than human tutors (the positive feedback loops make this inevitable) but how quickly we reach the knee in the curve, and whether we possess the wisdom to deploy this capability well.

A really, really uncomfortable truth about good teaching is that it doesn’t scale very well. Teacher expertise is astonishingly complex, tacit, and context-bound. It is learned slowly, through years of accumulated pattern recognition; seeing what a hundred different misunderstandings of the same idea look like, sensing when a student is confused but silent, knowing when to intervene and when to let them struggle. These are not algorithmic judgements but deeply embodied ones, the result of thousands of micro-interactions in real classrooms. That kind of expertise doesn’t transfer easily; it can’t simply be written down in a manual or captured in a training video.

This is why education systems rarely improve faster than their capacity to grow and retain great teachers. Pedagogical excellence replicates poorly because it resides not in tools or curricula but in people, and people burn out, move on, or are asked to do too much. Every nation that has tried to systematise good teaching eventually runs into the same constraint: human expertise does not compound exponentially.

So inevitably we return to the most promising ways of teaching and above all, one idea has endured more than any other.

The Ghost of Bloom’s 2 Sigma Problem

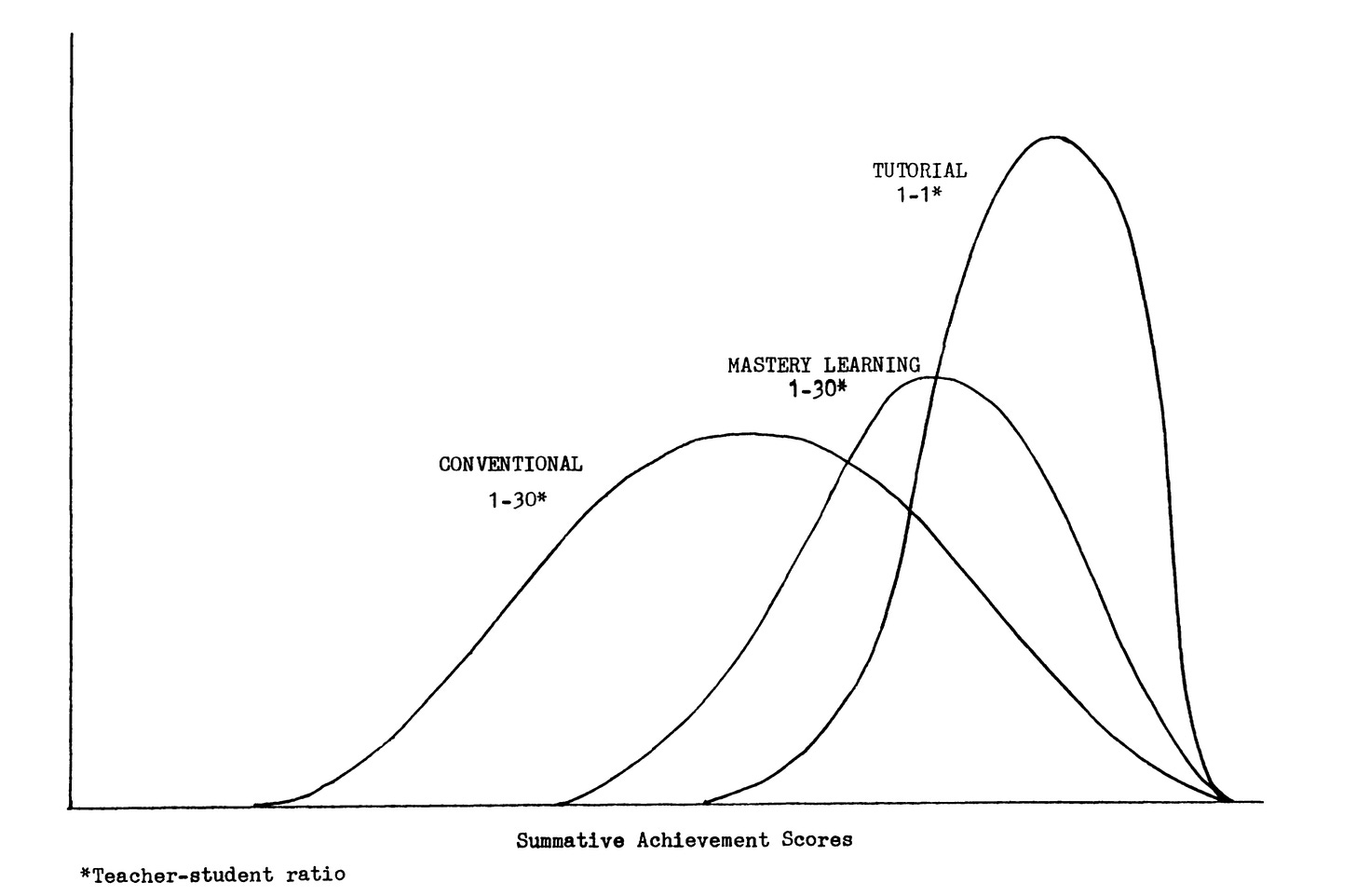

In 1984, Benjamin Bloom presented the education world with a challenge so significant that it has haunted researchers and practitioners for four decades. His finding was elegantly simple yet profoundly troubling: students receiving one-to-one tutoring performed two standard deviations better than those taught in conventional classrooms. Put differently, the average tutored student outperformed 98% of students in traditional classes.

Bloom’s conundrum has been the evidential base for edtech evangelists ever since, the holy grail of scalable, personalised instruction. For years, education has been chasing that missing mechanism: the means to reproduce the effects of expert tutoring without the cost or scarcity of human tutors.

However, there are some problems with Bloom’s famous study. Firstly, it never been replicated and secondly, the claimed 2.0 standard deviation improvement from one-on-one tutoring was based on just two dissertations using narrow tests with confounded interventions, while modern rigorous studies consistently find tutoring produces 0.30-0.40 SD effects, and even these effects drop by 33-50% when programs scale beyond small pilots.

But this is still meaningful; it represents moving students from the 50th to the 65th percentile. Systems like ASSISTments have demonstrated gold-standard evidence with effect sizes of 0.18 to 0.29 SD in large-scale RCTs involving thousands of students, and recent work with GPT-4 based tutoring has shown effects of 0.73 to 1.3 SD in controlled conditions, though replication at scale remains essential. What works consistently across the evidence is the combination of immediate feedback, spaced practice, adaptive personalisation, and mastery-based progression.

For forty years, we have tried to crack Bloom’s 2 Sigma Problem. Mastery learning approaches yielded approximately 1 sigma improvements; enhanced prerequisites and feedback-corrective procedures showed promise; peer tutoring and parental involvement demonstrated measurable gains. Yet none quite bridged the gap. The 2 sigma problem remained stubbornly unsolved, a reminder that our most effective intervention was also our least scalable. Until, perhaps, now.

Learning Either Obeys the Laws of Nature or It Doesn’t

To return to Penrose’s earlier provocation, what the emerging evidence is forcing us to contend with the question of whether learning is a physical phenomenon occurring in physical brains governed by physical laws, no more exempt from scientific investigation than photosynthesis or digestion. The alternative is that it represents the single exception in all of nature: a process that operates outside causation, measurement, and the possibility of systematic improvement. If that is the case, then education becomes an article of faith rather than a field of inquiry. Teaching would be an act of intuition, not design; learning an unpredictable miracle rather than a lawful process. It would mean that our efforts to improve instruction, to measure, model, and refine how people learn, are misguided from the start, because learning would belong to a realm beyond explanation.

We have models of this from other disciplines. For decades, the structure of DNA seemed impossibly complex, an enigma wrapped in the very substance of life itself. Yet when Watson and Crick mapped the double helix in 1953, they demonstrated that even the most fundamental biological processes yield to systematic inquiry. The mystery dissolved; the mechanism emerged. What followed was not the diminishment of biology but its transformation. We moved from reverent observation to deliberate intervention, from describing inheritance to editing genes.

If learning obeys physical laws, (and I think the evidence overwhelmingly suggests it largely does), then it is amenable to description, modelling, and ultimately, design. The question is not whether we can understand how learning works, but whether we possess the intellectual honesty to accept what the evidence reveals, even when it contradicts deeply held beliefs about classrooms, teaching, and the supposed irreducibility of human pedagogical relationships.

I know. As I type these words, I feel profoundly uncomfortable. Not so much because of what the current evidence says but because of what it points towards. If we take learning to be a durable change in long-term memory and if we take instruction as the key lever of that and if AI can teach better than humans, not as some distant possibility but as an emerging reality, then we must reckon with what that reveals about teaching itself.

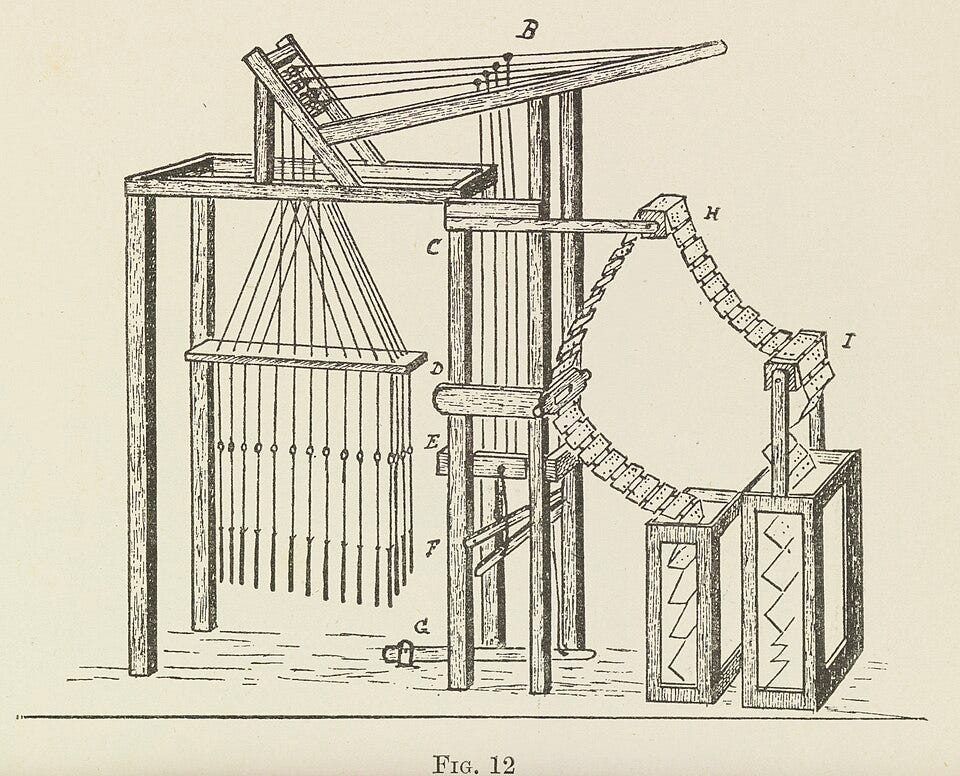

Efficiency Doesn’t Augment, It Displaces

There are many historical examples of skills we believed irreducibly human until they weren’t. When the Jacquard loom was invented in 1804, master weavers believed their craft to be irreducibly human. The rhythm of the shuttle, the tension of the threads, the subtle adjustments of hand and eye: these were the marks of expertise, learned through years of apprenticeship. Then a loom appeared that could reproduce their most intricate patterns automatically, guided by punched cards. The result was indistinguishable, and often superior. The weavers weren’t wrong that their work required skill; they were wrong about whether that skill was necessary.

If these emerging studies demonstrate what AI can do, it also raises a more uncomfortable question about what humans should do. If an algorithm can teach better than the average university instructor, what becomes of the instructor? The easy answer is that AI tutors will free teachers for higher-order tasks: discussion, mentoring, synthesis. Yet the history of educational technology suggests otherwise. Efficiency has a way of displacing rather than augmenting labour.

The authors of the aforementioned Harvard study themselves are measured. They argue that AI tutors should handle initial concept teaching and foundational practice, leaving class time for deeper reasoning and projects; a flipped classroom on steroids. Still, the boundary between “support” and “substitute” is porous. Once policymakers see large, statistically significant learning gains delivered at scale and at negligible cost, the economic logic becomes irresistible.

This is what makes studies like this so consequential. It doesn’t claim that AI can mark essays or generate lesson plans; it claims that AI can teach, and do so measurably better than some of the best human teachers in higher education. Perhaps what we’ve called “good teaching” is, in many cases, the skilled application of principles that can be formalised, modelled, and replicated. Perhaps the magic was simply engineering we didn’t yet understand.

AI Needs to Adapt to How Humans Learn Not The Other Way Round

One of my problems with the phrase the science of learning is that it’s really a refracted term. When we talk about retrieval practice in schools, we’re not really talking about retrieval in isolation; we’re talking about retrieving knowledge as it occurs in the wild; entangled with motivation, prior knowledge, attention, classroom climate, curriculum sequencing, and the unpredictable dynamics of thirty students learning together.

The clean laboratory effect becomes messy once it passes through the prism of real classrooms. What we call the science of learning is often the study of learning under highly controlled conditions, whereas teaching is the art of making those principles work amid constraint, noise, and variation. Often there is very little relation between the two.

But the domain of AI tutoring eliminates a lot of that noise. It doesn’t get tired, it doesn’t lose focus, it doesn’t have to manage thirty competing attentional systems at once. In theory, it delivers feedback at the exact moment it’s needed, never too late, never too soon. It adjusts the pacing not to the median of a class but to the learner’s individual rate of forgetting. It never forgets what the student has mastered or misunderstood.

Taken together, the findings from AI tutoring point to a pattern that echoes what learning-science has been telling us for decades. The systems that outperform human instruction aren’t “creative” or “sentient”; they are simply better at applying the known laws of learning, ones we have known for 100 years; explicit instruction, timely feedback, discriminating between varied examples, adaptive pacing, retrieval practice spaced out, and integrating new knowledge with old.

Once those principles are codified into algorithms, improvement conceivably becomes iterative and self-reinforcing. Each interaction produces data that refines the next, creating the kind of positive feedback loop that, as Kurzweil predicted, moves from gradual to exponential. The lesson here is not that AI has discovered a new kind of learning, but that it has finally begun to exploit the one we already understand.

But let’s be clear. Again, the history of Edtech is a story of failure, very expensive failure. This is not merely a chronicle of wasted resources, though the financial cost has been considerable. More troubling is the opportunity cost: the reforms not pursued, the teacher training not funded, the evidence-based interventions not scaled because capital and attention were directed toward shiny technological solutions. As Larry Cuban documented in his work on educational technology, we have repeatedly mistaken the novelty of the medium for the substance of the pedagogy.

The reasons for these failures are instructive. Many EdTech interventions have been solutions in search of problems, designed by technologists with limited understanding of how learning actually occurs. They have prioritised engagement over mastery, confusing students’ enjoyment of a platform with their acquisition of knowledge. They have ignored decades of cognitive science research in favour of intuitive but ineffective approaches. They have failed to account for implementation challenges, teacher training requirements, and the messy realities of classroom practice.

That distinction is exactly what Dan Dinsmore and Luke Fryer get at in their recent paper What Does Current GenAI Actually Mean for Student Learning? They argue that most generative AI tools are being dropped into classrooms with little regard for how learning actually develops. Using Alexander’s Model of Domain Learning, they show that expertise grows in stages; acclimation, competence, proficiency, and that each stage demands different kinds of scaffolding and feedback. Generic AI systems ignore this logic; purpose-built tutors can adapt to it.

Their warning is simple but profound: AI, in its current form, promotes fluency rather than understanding. It can simulate knowledge without cultivating it. The real promise of AI in education, they suggest, lies not in generating information faster, but in aligning its design with the fundamentals of learning itself. As John Sweller argued, “without an understanding of human cognitive architecture, instruction is blind.”

Beyond the Algorithm: Efficiency is Not Understanding

We may soon need to ask not just how AI can teach, but what kind of learning it produces. Fast learning is not always deep learning. Efficiency is not understanding. The Harvard results are notable, but they also invite the question at the heart of education: What do we want learning to be for? Perhaps the greatest danger is not that AI tutors will outperform us, but that they will redefine what counts as learning at all.

I’ve spent enough time in education to be sceptical of silver bullets. Every few years, a new intervention promises to revolutionise learning: smaller class sizes, interactive whiteboards, one-to-one computing, growth mindset workshops, learning styles, grit. Most of these turn out to be oversold. The evidence, when properly examined, is weak or inconsistent or has been misinterpreted.

Perhaps the answer is that teaching and learning are not the same thing, and we’ve spent too long pretending they are. Learning, the actual cognitive processes by which understanding is built, may indeed follow lawful patterns that can be modelled, optimised, and delivered algorithmically. The science of learning suggests this is largely true: spacing effects, retrieval practice, cognitive load principles, worked examples; these are mechanisms, and mechanisms can be mechanised. But teaching, in its fullest sense, is about more than optimising cognitive mechanisms. It is about what we value, who we hope our students become, what kind of intellectual culture we create.

John Keats wrote of the mind as possessing a ‘wreath’d trellis of a working brain’ an image of organic complexity that resists simple mechanism. Perhaps this is what we fear losing: not just the efficiency of human teachers, but the tangled, mysterious process by which one mind awakens another.

Penrose asked whether consciousness can be computed. The evidence from AI tutoring suggests that instruction can be. But whether instruction and education are the same thing remains an open question. We stand at an inflection point where the technology is here, it’s improving exponentially, and pretending otherwise won’t make it go away. The question is not whether AI will transform education; it clearly already is. The question is whether we have the courage to design it around evidence and human flourishing, or whether we’ll simply let it happen to us.

With the wreath’d trellis of a working brain,

With buds, and bells, and stars without a name,

John Keats

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-97652-6.pdf

https://www.cell.com/trends/cognitive-sciences/abstract/S1364-6613(25)00249-9?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1364661325002499%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

Well, yes, as a teacher I find this somewhat unsettling. I’m starting to feel somewhat obsolete.

I’m not sure the progression will be unstoppable. As far as I know, there are intrinsic limitations to what an AI can do, as generative AIs are not general intelligences, yet. Even so, what these tutors can do right now is remarkable, to say the least.

Admitting my undeniable bias in this whole matter, I’d try to suggest a few thoughts (which in some cases echo what I’ve read here).

The most striking thing is that an AI tutor has the advantage of being ubiquitous, while a teacher can only work, at best, with one person at the time. In this regard, AI tutors have already won and settled the question.

As for the Harvard study, it must be noted that AI tutors were used with college students, that is, with students who are already, by and large, good independent learners. My impression is that this kind of tutors might work particularly well with people who are able to ask purposeful questions, weigh the answers and put them to good use. Most importantly, these are solidly and deeply motivated learners. In other words, my tentative hypothesis is tha AI tutors work particularly well with autodidacts.

I’m not sure the same applies to less experienced learners, albeit some of the studies you quoted seem to provide an at least partially positive answer.

That said, and considering that, ironically, after some twenty years in the teaching profession I’m starting to feel particularly effective thanks to the mastery I’ve eventually acquired in DI (which I embraced three years ago), I am not entirely assuaged by my own reassurances.

Orwell said something about wanting to make political writing an art. I think you have with education, Carl.