Making Retrieval Practice Actually Work

Seven Essential Principles for Teachers to Know

" Learning is altered by the act of retrieval itself. Every time a person retrieves knowledge, that knowledge is changed, because retrieving knowledge improves one’s ability to retrieve it again in the future." (Karpicke, 2012)

Retrieval practice, the act of actively recalling information from memory rather than simply re-reading or reviewing it, is one of the most powerful evidence-based learning strategies we have. However, despite its proven effectiveness, implementing retrieval practice effectively in the classroom remains challenging.

For example, I'm seeing many schools mandating retrieval practice at the start of every lesson, but often it isn't having the intended impact. A key part of implementing the science of learning is to understand the deeper underlying principles at work so teachers can make better decisions in their classrooms. Here are 7 critical considerations for fine-tuning retrieval practice:

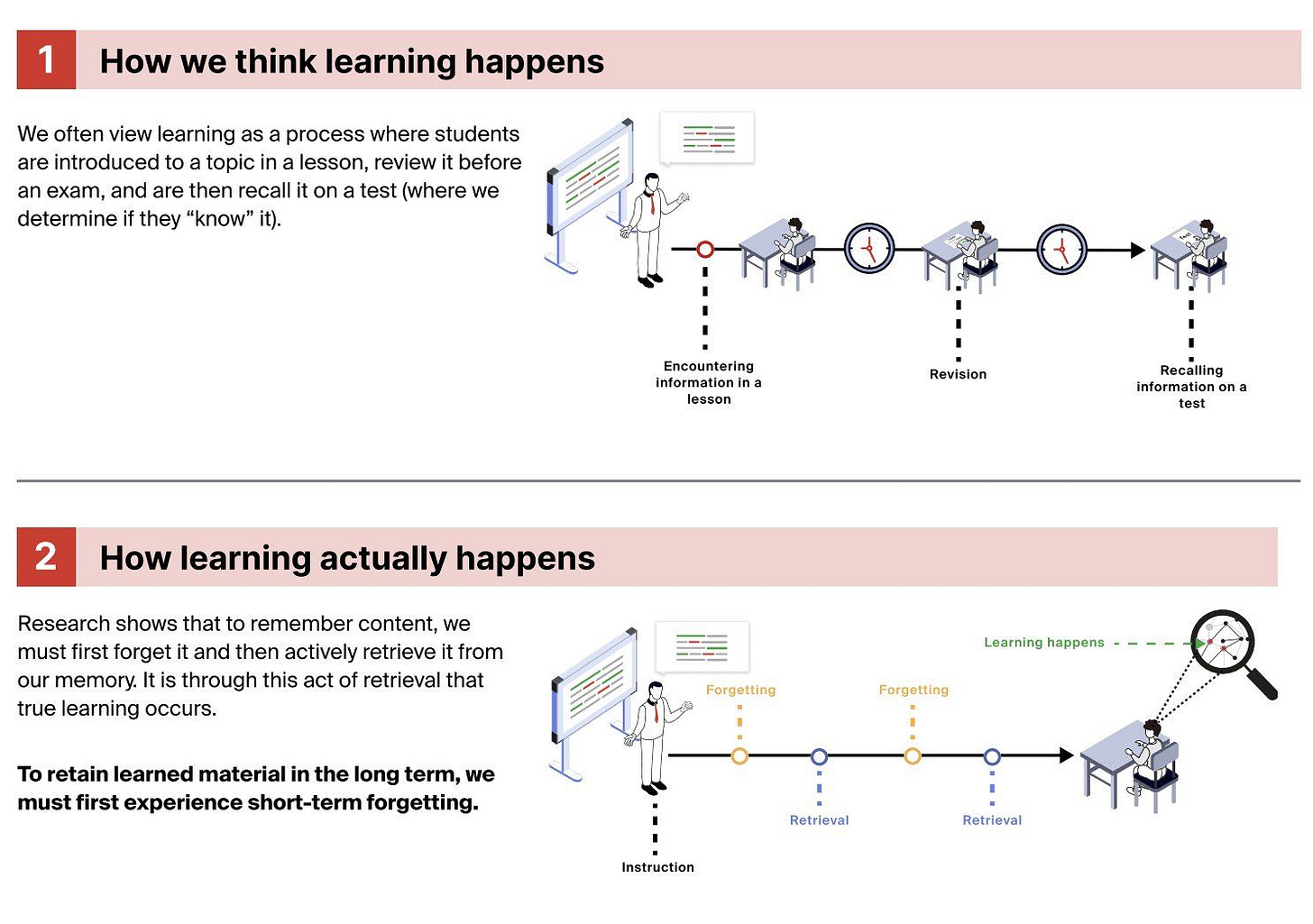

1. The Paradoxical Power of Forgetting

One of the really bizarre things about learning is how utterly counterintuitive it is. For example, when we retrieve information after a period of partial forgetting, our brains engage in a more effortful reconstruction process that actually strengthens the long-term memory trace. In this respect, learning is an interstitial act - it occurs in the spaces between things.

Many of the things which feel like learning often lead to the opposite outcome. For example, cramming for an exam might help in the short term but typically leads to poor long-term retention, while spaced practice that allows for some forgetting between study sessions leads to more robust and lasting learning.

As Robert Bjork explains, the very act of forgetting creates the conditions necessary for stronger relearning, making temporary forgetting a feature, not a bug, of how our memory systems work.

2. Use retrieval practice as a learning event not a testing event

While retrieval practice can provide valuable information about student learning, its primary purpose should be to enhance learning, not just to measure it. When retrieval practice is used solely for assessment purposes, it can create anxiety and pressure, which can be detrimental to learning, especially if it's high-stakes. Retrieving information from memory actually strengthens it, making it more likely to be recalled in the future. This highlights the active nature of retrieval practice and its potential to solidify learning.

The more we can get students into the habit of basically just ‘having a go’ at stuff without absolute judgement or measurement, the better their learning will be. Errors are valuable learning opportunities, and retrieval practice can help uncover them. Rather than simply marking answers as right or wrong, teachers should encourage students to analyze their mistakes and understand why they made them. The point of retrieval practice is not so much to find out find out what students have learned but to actually be a learning event in and of itself.

3. Make sure to provide enough challenge, especially initially

Giving quizzes, where the first retrieval is very soon after learning, can create the "illusion of competence" where students recall easily on that first attempt, but later performance suffers. The initial retrieval needs to be sufficiently challenging to be effective. Easy retrieval often involves retrieving information based on superficial cues or associations, rather than engaging in deeper, more elaborative processing. This type of shallow processing can lead to memories that are fragile and easily forgotten. When retrieval is effortless, the brain doesn't need to work as hard to retrieve the information. Evidence suggests that this lack of effortful retrieval can result in weaker encoding of the memory trace, making it less durable over time.

Similarly, retrieval practice can lead to fluency, but fluency doesn't always equate to understanding. Teachers should be wary of the "fluency illusion" and use retrieval practice in conjunction with other methods to assess genuine comprehension. This is similar to how we might recognise a song we've heard many times without necessarily understanding the lyrics or the musical structure. Recognising that a problem us a quadratic equation is not the same as being able to solve it.

Two keys things to bear in mind:

Shallow Processing: Fluency can be achieved through rote memorization or shallow processing, where students focus on remembering isolated facts or procedures without connecting them to underlying principles or applying them in new contexts.

Context-- Dependent Memory: our ability to retrieve information is often influenced by the context in which we learned it. If retrieval practice always occurs in the same context (e.g., using the same type of questions, in the same classroom setting), students may develop a false sense of mastery because the retrieval cues are always present. However, when they encounter the material in a different context (e.g., on an exam, in a real-world application), they may struggle to recall or apply the information.

4. Make sure to space out retrieval practice

One thing about retrieval practice is that it doesn’t work without spacing it out over time, in other words it’s not a ‘one and done’ thing. Like initial learning, retrieval practice is most effective when it's distributed over time. Frequent, short quizzes or retrieval activities over time are more beneficial than a single, lengthy review session right before an exam.

We can make a distinction between two types of memory strength: retrieval strength (how easily information can be accessed at a given moment) and storage strength (how well information is consolidated into long-term memory). Spaced retrieval practice strengthens both types of strength. When we retrieve information after a period of forgetting, it's more effortful, and this effortful retrieval leads to greater storage strength, making the memory more durable.

5. Connect retrieval practice to curriculum

If you’re planning your curriculum without considering how to make itRetrieval practice should be meaningfully integrated into the curriculum and aligned with learning objectives. Randomly asking students to recall facts without any context or purpose is unlikely to be effective. (Stop getting random kahoots off the internet).

Two main reasons why this is a problem:

Lack of relevance and meaning: When retrieval practice activities are not clearly linked to the curriculum or learning goals, students may perceive them as irrelevant or busywork. This lack of perceived relevance can decrease motivation and engagement, making it less likely that students will invest effort in the retrieval process, which is essential for its effectiveness.

Ineffective encoding and retrieval cues: Our memories are not like video recorders; we don't store information in isolation. Instead, we encode information in relation to its context and meaning. When retrieval practice activities lack context or purpose, the retrieval cues are weak, making it more difficult for students to access and make sense of the information. They key point here is that learning is about making multiple connections between items of knowledge not atomised recall of isolated information.

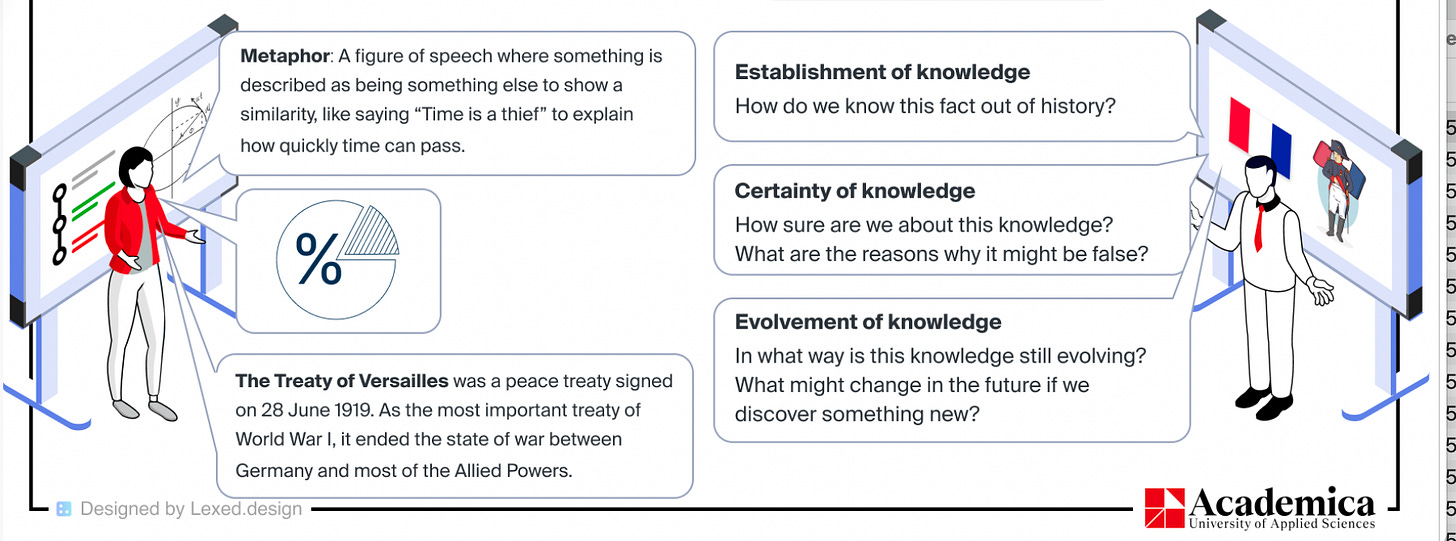

The distinction between substantive and disciplinary knowledge: Subject disciplines have their own ways of thinking, practicing, and knowing. Effective retrieval practice should reflect these disciplinary differences. For example, in history, retrieval shouldn't just focus on dates and events (substantive knowledge) but also on historical thinking skills like causation and interpretation (disciplinary knowledge). In science, it's not just about recalling facts but understanding scientific processes and methods of inquiry.

6. Explicitly teach students retrieval strategies

Teachers may assume students inherently know how to effectively use retrieval practice. However, retrieval is a skill that can be improved with instruction and practice. Teachers should explicitly teach students different retrieval strategies. Retrieval practice isn't limited to simple quizzes or flashcards. It encompasses a variety of strategies that require different levels of cognitive processing and can be adapted to different learning goals. Teachers should explicitly introduce students to these various strategies, including:

Elaboration: elaboration goes beyond simple recall and encourages students to explain concepts in their own words, provide examples, make connections to prior knowledge, and explore relationships between ideas. When students explain concepts to themselves or others, they engage in powerful retrieval that forces them to reconstruct their understanding. Teach students to ask themselves: "How would I explain this to someone who doesn't know anything about it?" This process reveals gaps in understanding and strengthens connections between ideas.

Generative Retrieval: Show students how to generate their own questions about the material rather than just answering pre-made questions. This might involve creating their own practice problems, predicting potential test questions, or identifying key concepts that deserve deeper exploration. This approach develops metacognitive skills alongside content knowledge.

Concept Mapping and Visual Organisation: Guide students in creating visual representations of knowledge that emphasise relationships between ideas. However, the key is to have students create these maps from memory rather than simply copying from notes or texts. Teach them to:

Start with main concepts

Add supporting details through active recall

Draw connections between different elements

Revise and refine their maps as understanding deepens

Integration Practice: Train students to deliberately connect new information with existing knowledge. This might involve:

Comparing and contrasting new concepts with familiar ones

Finding real-world applications of theoretical ideas

Identifying patterns across different topics or subjects

Explaining how new information changes or enhances their previous understanding

There are a lot of ways to approach this. A great place to start is the work of John Dunlosky.

7. Keep it low stakes

Retrieval practice is most effective when it's low-stakes and stress-free. High-stakes tests, while sometimes necessary, can trigger anxiety that interferes with retrieval and reduces the learning benefits. When students consistently associate retrieval practice with high-stakes assessments and the fear of failure, it can create a negative feedback loop. Students may start to avoid challenging tasks or learning opportunities that could lead to errors, hindering their overall academic growth. Frequent, low-stakes retrieval practice is key. Make retrieval practice a regular and integrated part of instruction, but with low or no stakes attached. By frequently engaging in retrieval practice, students become more comfortable with the process of retrieving information, and it becomes less daunting.

These are largely theoretical considerations and in future posts I want to explore how retrieval practice needs to be planned closely with spacing and interleaving, and examine how these strategies work together synergistically with classroom-specific practical examples.

References and further reading:

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (1992). A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In A. Healy, S. Kosslyn, & R. Shiffrin (Eds.), From learning processes to cognitive processes: Essays in honor of William K. Estes (Vol. 2, pp. 35-67). Erlbaum.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students' learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4-58.

Karpicke, J. D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.

Pan, S. C., & Rickard, T. C. (2018). Transfer of test-enhanced learning: Meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 144(7), 710-756.

Carpenter, S. K., Cepeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to enhance diverse forms of learning: Review of recent research and implications for instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 369-378.

Thanks to Alex Koks for the visualisations, all taken from the HTLH course.

This is an excellent primer! Thank you.

受益匪浅。我会改进我的教学流程