Cognitive Ventriloquism: Why Students Give the Right Answers for the Wrong Reasons

The Clever Hans Conundrum: Performance Without Understanding

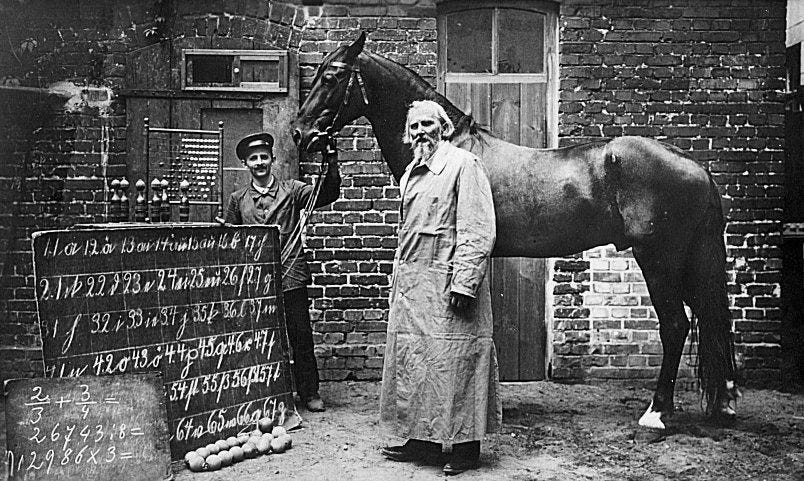

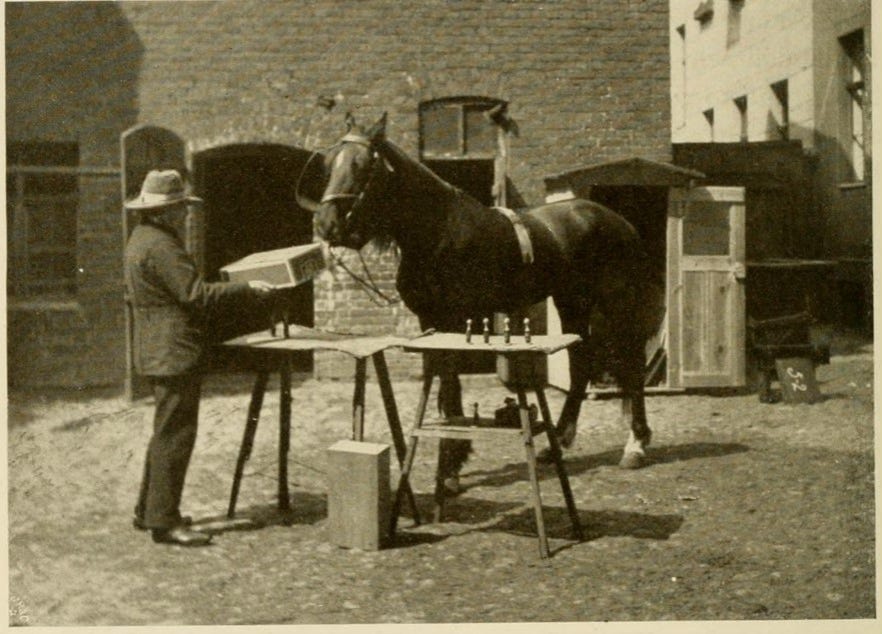

In early 20th century Berlin, a horse named Clever Hans captivated the public imagination. Owned by Wilhelm von Osten, a mathematics teacher, Hans appeared to perform remarkable feats of intelligence such as solving arithmetic problems, identifying musical tones, and even answering complex questions through a system of hoof taps. Spectators were astonished by this seeming display of intellect, and Hans became an equine sensation across Europe.

The mystery of Hans's abilities attracted the attention of psychologist Oskar Pfungst, who conducted a series of rigorous experiments in 1907. His findings revealed something profound - Hans wasn't actually calculating at all. The horse was responding to subtle, unconscious cues from his questioners with minute shifts in posture, facial expressions, and breathing patterns that occurred when Hans reached the correct number of taps. When the questioners didn't know the answers themselves or when Hans couldn't see them, his "mathematical abilities" vanished.

By providing the horse with blinders, which restricted his visual field to directly ahead, Pfungst created controlled conditions to test Hans's purported abilities. The results were striking and unambiguous. When Hans could observe the questioner, his accuracy soared to an impressive 89% – a performance that, to casual observers, appeared to confirm the horse's mathematical prowess. However, when the questioner stood to the side, positioning themselves outside Hans's field of vision, the horse's success rate plummeted dramatically to a mere 6%, barely above what random chance would predict.

This discovery gave rise to what we now call the "Clever Hans Effect", a phenomenon where an animal or person appears to demonstrate sophisticated understanding but is actually responding to inadvertent cues from those around them. What makes this effect so powerful is that both parties are typically unaware of the dynamic at play. The story is compelling not just for its novelty, but because it mirrors a persistent issue in education: students often give correct answers not because they understand, but because they’ve learned to read us.

Cognitive Ventriloquism

I am often guilty of the Clever Hans effect with my own daughters. We have twins and when I’m helping them learn letter/sounds and I often find myself asking what a particular letter sounds like when one of them will start to sound out a letter; "ahhhh" to which I will often raise my eyebrows in anticipation, nodding slightly when they approach the correct pronunciation. When they hesitate, I unconsciously lean forward, perhaps even mouthing the sound myself.

This kind of thing is familiar to many parents and teachers and not just in terms of visual cues. In many cases, we conflate performance for learning without even realising it. These instances of cognitive ventriloquism aren't deliberate pedagogical strategies—they're unconscious behaviours that both educators unwittingly participate in because we’d rather perform a kind of elaborate ruse of understanding with them than confront the discomfort of genuine uncertainty or struggle.

Cognitive ventriloquism operates through several mechanisms:

Unconscious Cueing: Instructors provide subtle signals such as nods, facial expressions, voice modulations etc that guide students toward expected responses.

Question Framing: The structure of questions often contains embedded cues about desired answers, allowing students to respond correctly without understanding underlying concepts.

Environmental Scaffolding: Classroom environments can be constructed in ways that provide excessive support, removing the need for independent thinking.

Feedback Patterns: The timing and nature of feedback can train students to detect what the teacher wants rather than develop authentic understanding.

In each case, what appears to be understanding is actually a sophisticated response to environmental cues. The student, like Clever Hans, learns to perform in ways that simulate understanding without necessarily achieving it.

Robert Bjork’s distinction between learning and performance is helpful here (again). According to Bjork, performance (what students can demonstrate during instruction) is often a poor indicator of actual learning which is what they have retained and can apply later. Bjork's research demonstrates a counterintuitive principle: conditions that maximise immediate performance often minimise long-term learning, while conditions that create difficulties and even impair immediate performance often optimise long-term retention and transfer.

This fallacy helps explain why cognitive ventriloquism is so pervasive and problematic. Educational environments rich with cues produce high immediate performance (the illusion of understanding) while potentially undermining long-term learning (genuine conceptual change in long term memory).

The ultimate fate of Clever Hans remains a mystery. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he was conscripted into military service, where records suggest he either perished in battle around 1916 or, in a much grimmer possibility, became food for famished soldiers during the war's desperate conditions.

The lesson of Clever Hans isn't simply about a horse that couldn't really count. It's about our profound human tendency to see what we wish to see and to inadvertently train others to validate our expectations. There’s a thin line between necessary scaffolding and excessive cueing where we risk cultivating performers rather than autonomous thinkers. The true measure of effective instruction lies not in how well students perform in our presence, but in how capably they think on their own when we step outside their field of vision.

On the other hand, there are those who hold that the initial steps of learning (i.e., imitation) as "mimicking" and "not thinking". Imitation is necessary but not sufficient, it's true. But those in the progressive camp of math education focus on the "not sufficient" part of it, and hold imitation of any type in disdain, with the belief that it eclipses "true understanding" whatever their definition of "true understanding" is.

As anyone knows who has learned to play an instrument, learned a golf step, bowling, a dance step, imitation is harder than it looks. With scaffolding, the imitation of a procedure becomes linked to reasoning with it. It serves as a foundation upon which more sophisticated approaches are attached.

I hear the complaint often that "traditional math" does not teach understanding. It is not the case that we teach procedures without context; i.e., "do this if you want to find the discounted amount" or multiplication facts without teaching that it represents repeated addition, etc. We do teach for understanding; we just don't obsess over it, for fear that we are creating "Clever Hans" students. Kids naturally want to know "how to do it", and focus on the procedure more than the understanding piece of it. It doesn't mean that they are learning only the procedure -- some of it sticks, and as the foundational knowledge is added to, they understand more of what it is the procedure represents.

This seems like a spectrum. Not only for feedback from the teacher/parent that gives the cue to the right answer, but also when giving the right answer without understanding.